by Siba Kumar Das

Open till March 12, 2022, this is Aicon Art’s third solo show celebrating the art of Rachid Koraïchi—humanist, polymath, creator of art carrying universal significance. While originating in a culture permeated by Quranic scholarship and Sufi mysticism, his art crosses artistic frontiers going beyond Islamic calligraphy and inscription. In inventing a unique artistic language, Koraïchi draws upon many languages and cultures, including those of the Berber and Tuareg peoples. Within his fold, too, are invented Chinese ideograms plus magical squares and talismanic glyphs and other auspicious signs. Also most impressive is the range of his materials, the employment of which has often inspired the artist to create a symbiotic partnership with designers and artisans around the globe.

In June 2021, in the presence of Audrey Azouley, UNESCO Director-General, Koraïchi inaugurated at Zarzis, Tunisia, Le Jardin d’Afrique, at once a graveyard, garden, and art installation dedicated to the thousands of migrants who have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean. Built with his own funds, he plans to expand the project to serve regions other than Africa and is seeking additional support. The cemetery is non-denominational, and it includes an interfaith prayer hall and a DNA data base for identifying the dead. Hand-crafted tiles from Nabeul, Tunisia, hand-fitted by local artisans, decorate its walkways. In the garden, five olive trees symbolize Islam’s five pillars, while twelve vines reference the twelve Christian apostles. The garden-installation serves as a backdrop to the Aicon Art show, and many works on display allude to it.

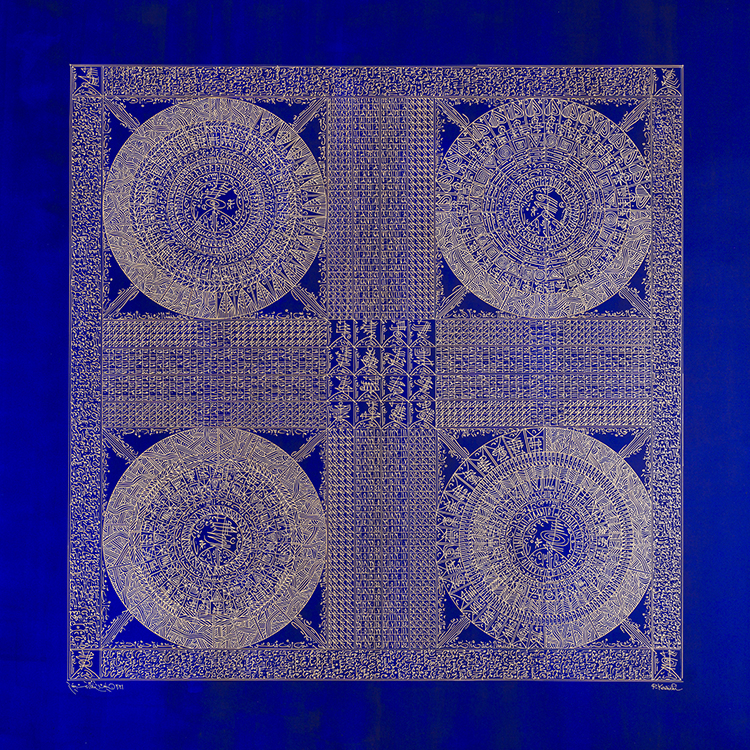

The show is divided into three groups of art objects with a single work, a large tapestry, being a fourth. Fourteen acrylic canvases present linen-like tablets intricately inscribed with golden filigree-like letters, glyphs, ideographs, and other signs, all set in a deep indigo background that also frames the tablets. Dedicated to La Montagne aux Étoiles (Mountain of Stars), which may be seen as an allusion to the Jabal al-Nour (Mountain of Light) on which the Prophet received God’s word through the angel Gabriel, the paintings seem lit from within. The effect is one of sublimation emerging from a world of bejeweled beauty: it’s as if Koraïchi is seeking a language that lies beyond language.

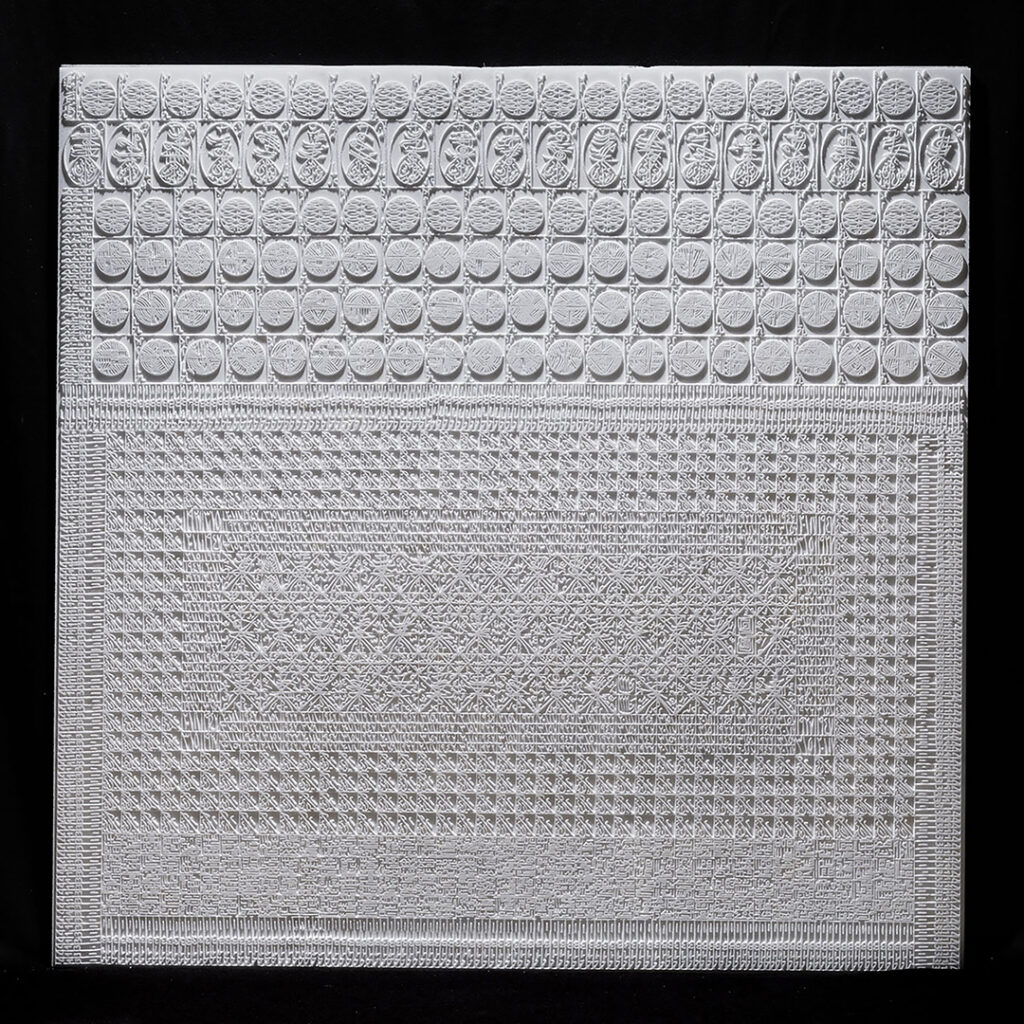

Alabaster is today largely used as a medium for small sculptures and decorative objects. The Oxford Companion to Art also tells us that alabaster’s “smooth, polished surface offers little scope for subtleties of texture.” Seen in light of these factors, it is notable that the six sculpted and incised alabaster wall tablets on display at Aicon Art are four times larger than Koraïchi’s earlier alabaster works. Moreover, working with traditional artisans, he has created textured surfaces so subtle, so intricate, so replete with meticulously and painstakingly achieved detail, you would think you are looking at finely woven wall hangings. If text can be ‘woven fabric’, as Roland Barthes thought, so can Koraïchi’s alabaster tablets, ‘written’ in a language beyond language. As you gaze at the tablets, you might recall the immensely long history of alabaster usage in both West Asia and North Africa—ancient Mesopotamia and Pharaonic Egypt included—and wonder at the reinvention in of this tradition hanging on Aicon Art’s walls.

The title the alabaster tablets share in common—Le Chant de l’Ardent Désir (The Song of Burning Desire)—makes you think of the Sufi mystic and poet Jala al-Din al-Rumi, who lived in the thirteenth century and whose life and work inspired Koraïchi to create Path of Roses, a large, multi-media installation that has been exhibited at multiple locations and is represented at The British Museum. Al-Rumi sang of desire and yearning in the context of love, both love of the world and love of God. Translator Coleman Barks says, “Everyone knows the story of how representatives from all faiths came to [al-Rumi’s] funeral.” This is Barks again: “His place among world religions is as a dissolver of boundaries.”

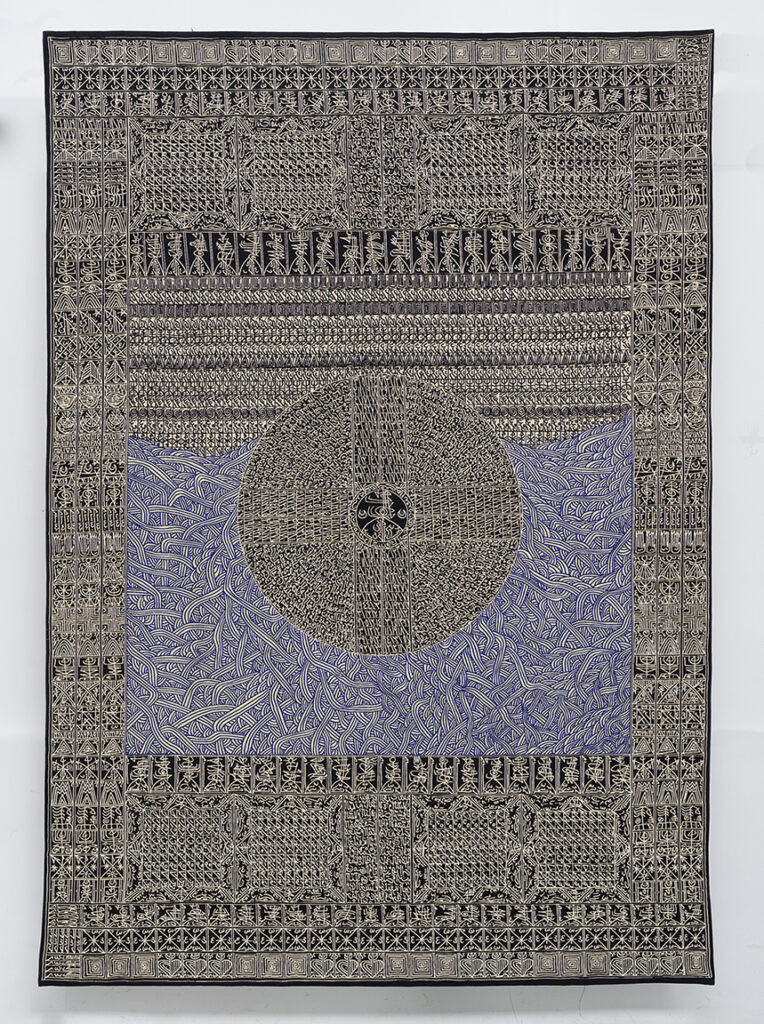

Think of this dissolution of boundaries when you view, in the room where the alabaster tablets are displayed, the large woven tapestry titled Jardin d’Afrique. You might see now that it is Rumi’s message of oneness amid multiplicity that Koraïchi opens up for you when you visit his garden at Zarzis. That oneness seems to be especially symbolized by the spherical object in the tapestry’s center—the idea of unity reinforced by the cross within the sphere, the cross being a crossroads. You cannot escape noticing, however, that the symbolic sphere is beset by seething sea-waves—the waves of the Mediterranean. Koraïchi’s garden is a haven of beauty and peace; it’s also a call to action.

Bordering the tapestry’s central images is an assemblage bringing together multitudinous elements of Koraïchi’s unique visual language. Note especially the row after row of anthropomorphic objects that seem to marry Arabic calligraphy with Chinese ideograms. Think, is this not suggestive of a gate you could open to a more cross-cultural world?

Lining the path to the monumental tapestry are seven steel structures which represent the translation of Koraïchi’s anthropomorphic images into shadow-casting sculptures. These sculptures represent a distinct branch of his oeuvre that he invented some years ago and that looms large in his imagination. Titles and significations, together with the exact shapes of images, vary from installation to installation. For instance, back in 2008, in another context, Koraïchi shaped them as Les Priants (The Supplicants). For his present purpose, the artist shapes them differently, making them warrior-like, and calls them Les vigilants, la Nuit (Night Sentinels), perhaps suggesting that they both protect and are one with the souls buried in Le Jardin d’Afrique.

If you return to viewing Koraïchi’s acrylic paintings and alabaster tablets, you will find in them different renditions of his anthropomorphic imagery. They are ubiquitous in his art and seem to symbolize the humanism that drives his art and activism. In the naming of the Aicon Art show as Le Chant de l’Ardent Désir, there is a purposefulness. Its glowing beauty is a cry in a world of fissures and fractures.

Rachid Koraïchi: Le Chant de l’Ardent Désiris on view through March 12, 2022 at Aicon Art, 35 Great Jones Street, New York, NY 10012.

Koraichi was born in Ain Beida, Algeria, in 1947 and now lives and works in Paris, with major projects in Algeria, Egypt, Spain, Tunisia, the U.S.A., and Dagestan.