by John Mendelsohn

What is painting magic? How do we recognize it? What is it good for?

These questions arise from thinking about the work of Jeffery Bishop and Mason Dowling in their current two-person exhibition. Both artists employ painterly processes of their own invention, creating personal genres of image making that move us beyond wondering “How did they do that?”. Part of the fascination engendered by both artists is the slight-of-hand of seductive effects, misdirecting us while something else is transpiring, just beyond our conscious awareness.

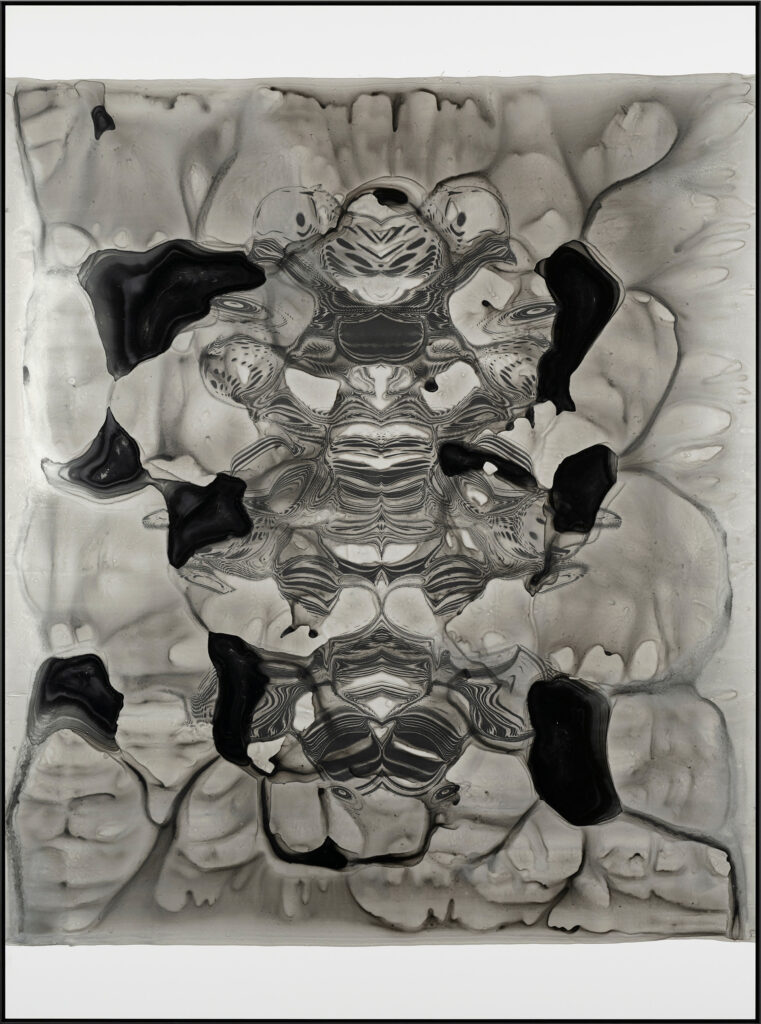

In Bishop’s case, a silkscreened or collaged image often become a central motif, with a seemingly generative power to create a confounding visual field in turmoil around it. In the artist’s two large Fathom Compression pieces, a complex, symmetrical, silkscreened form anchors the billowing of diluted ink, a mysterious grisaille realm of liquid of pools and crevasses. The innermost form can be read as a kind of holy monster, or wizard behind the screen, whose identity is subsumed by the tempest he creates. Both the ink’s unpredictable flow, and the work’s title alert us that we have entered a realm of consciousness where sinking into its depths carries both wonders and perils.

In Bishop’s Sidewinder series, a writhing, nubile form, applied to the painting’s surface as a chine collé, moves like a spill of mercury or a dancing, cybernetic demon. This avatar rules over a small kingdom whose landscape is comprised of an archive of the artist’s favored graphic motifs. In Sidewinder #6 a snaky cadmium red shape overlays Bishop’s spears, streamings, and distressed surfaces.

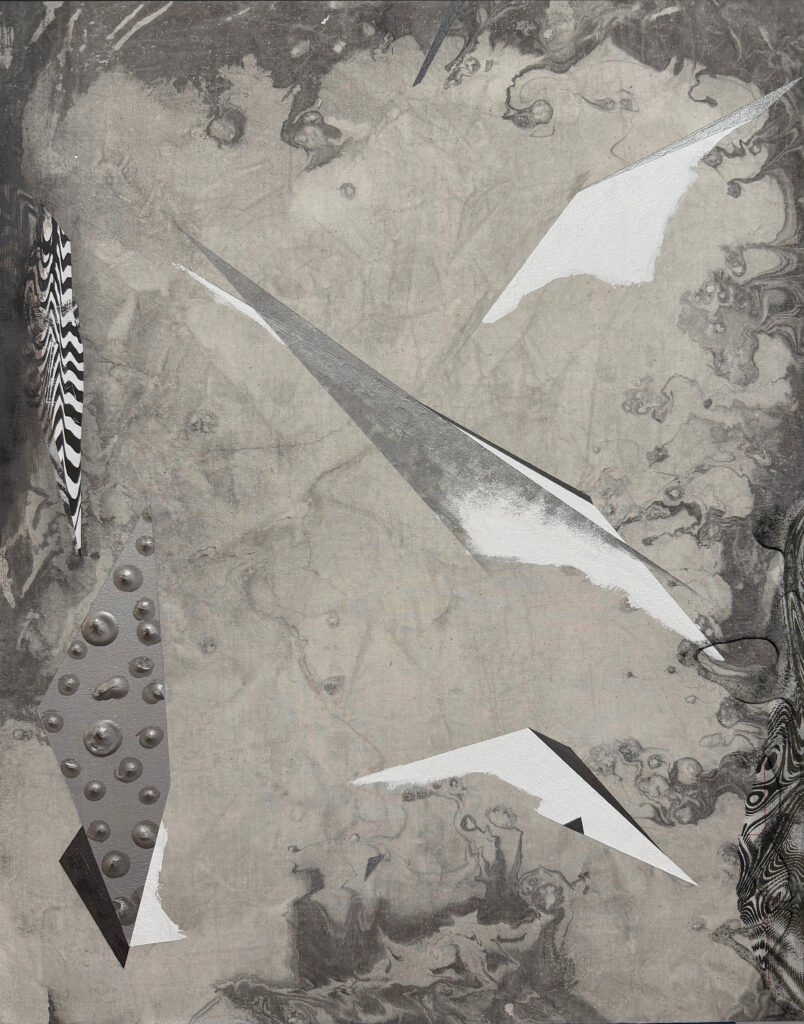

Bishop’s Interval pieces are perhaps the most intimate and personal works here. In these paintings, cotton on panel act as a kind of private diary, carrying a gritty atmosphere of grayed tendrils acrylic, fragments of vibratory waves, and trapezoids studded with peaked studs of silver paint. In Interval #8, shards of white wings float high above the miasma that they have escaped.

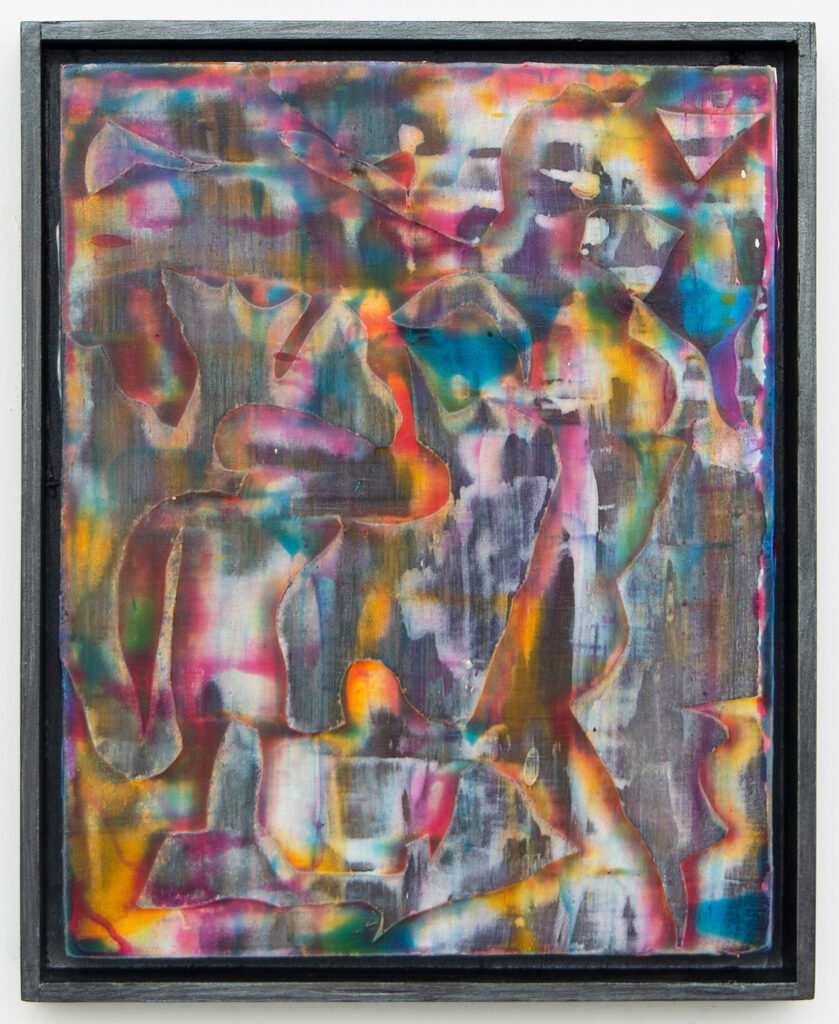

Mason Dowling creates hallucinatory paintings with a deceptively simple method – cut paper affixed to a panel, squeegeed with passes of color. The result is a gorgeous field of flaring hues that appear and fade away unpredictably. Complicating matters, the cutaway shapes catch darkness within them, spilling shadows onto the surrounding surface. The effect is a kind of solarization, with negative and positive trading places within a single painting.

For all their beauty, there is a sublimated fierceness at work here, with the sharp forms cut into the surface, and the charred shadows that threatens the streaks of cerise, scarlet, and gold. There is, as well, a kind of temptation at work: we are asked against our better judgement to trade the pleasure of looking, only to find the risk that lurks as the price of the bargain.

A number of the painting feature a softened, almost blurred appearance that seems to allude to the natural world, specifically to the high desert of New Mexico, where the artist was raised. We can see in these and other paintings the weathered geology, the powerful light, and scorching heat of this environment.

Two of Dowling’s largest works are structured by an all-over field of vertical lines, perhaps off-printed from corrugated cardboard. Cutt (Trucha) combines cut forms with these deep striations, and a shimmering, almost iridescent sunset light, an evocation of the cutthroat trout, native to the American West.

Both Bishop and Dowling share a version of painting magic that allows them to conjure, through abstract, material means their own psychic dominions, into which we are induced to enter.