by Mary Hrbacek

Nathaniel Mary Quinn, “Not Far From Home; Still Far Away,” at Gagosian, presented an exploration of Quinn’s relationships in fourteen intense portraits, created in a range of media that includes oil paint, gouache, charcoal, oil stick and pastel. Distortion is the keynote of Quinn’s inner-based perception, expressed in a vision that transforms the artist, his friends and his female subject, apparently his mother. He disregards visually perceivable features, boldly executing truncated, layered, re-imagined, and spliced images that exude a sense of deep emotional anguish. Quinn’s impeccable inventive paintings compare with the visceral images Francis Bacon created in his portraits, and Picasso’s Synthetic Cubist women.

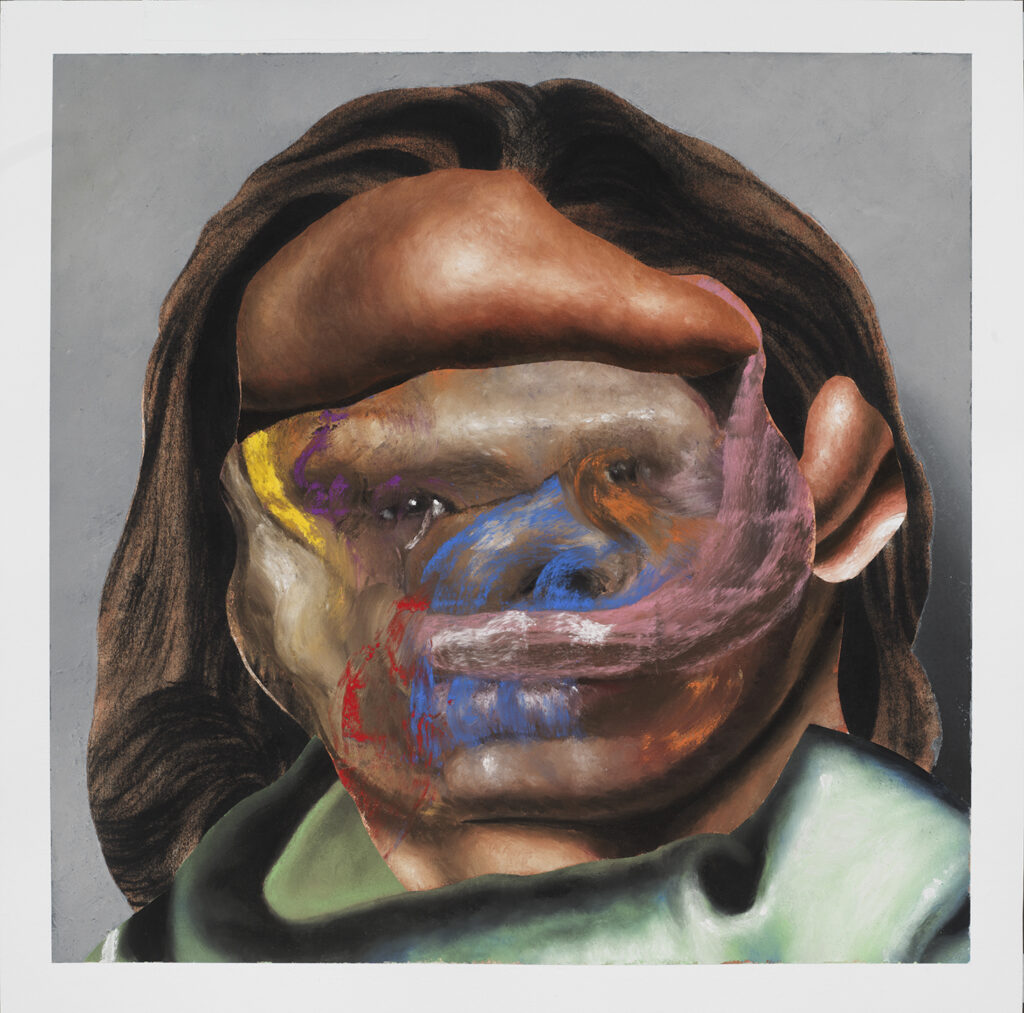

While the term “ugly” applies, it does not define these transformative works. Disfiguration often evokes pity; here it signals the existence of an evolving inner turmoil, in the emotional process of reconciliation. While the works recall Willem De Kooning’s displacement of anatomical parts and features, the fleshed out volumetric forms disclose an almost sculptural depth and attendant feelings. Quinn depicts enlarged lips and twisted rebooted noses that speak of his strongly sensory nature. He renders the ears askew on opposite sides of the head, hinting at the malleability of sound, when we sometimes hear what we want to hear. These portraits are the opposite of Bronzino’s ultra-smooth surfaces and “pretty” faces, but they convey the same quality of truth.

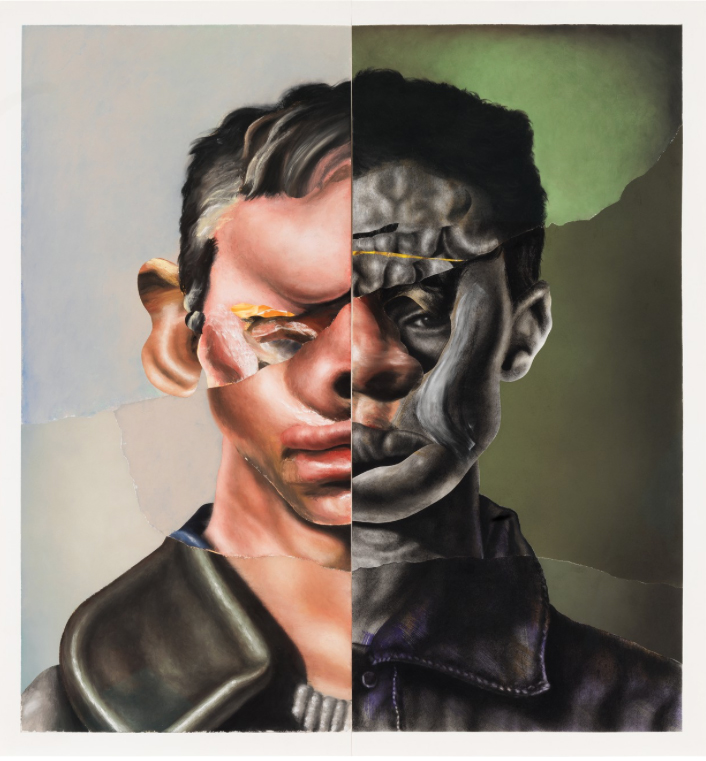

The fierce authenticity Quinn displays in his departure from the Greek aesthetic of symmetry and beauty, as portrayed in Western Art, makes these works all the more distinctly poignant. The formats rely almost entirely on the heads, and in some cases the subjects’ bodies. There isn’t much extraneous detail or information to distract from the main focus which resembles a cinematic crescendo at the height of its climax, or a seething volcano which is about to erupt. The jaunty hats and clothes add hints of imaginary or possibly real roles Quinn plays with, adding dimension to his reconfiguration of past life and people whose influences have contributed to his adult character. The titles indicate the autobiographical underpinnings of this body of works. It took creative courage to articulate the blood and saliva that seem to gush from the subject’s face and mouth in “The lesson of Cut Rate Liquor.” In the brilliant “Double Barreled Shotgun,” he seems to indicate a dual personality, with aspects of his black identity inside and a white persona outside. Quinn’s creative process is an instinctive battle for regeneration and renewal, keeping every stroke and form in control; I doubt that accident plays much of a role. Dream imagery does not seem evident in these works, but his titles are certainly dramatic. The works are the outcome of engaged skirmishes to reclaim a measure of peace and self-understanding through art making, that is essential in a challenging life.

Quinn’s work is an example of the level of commitment the twenty-first century public deserves to see. It is relevant to the critical issues we face in the world today. Personal stress and conflicts parallel the global climate crisis, but many painters overlook the importance of authenticity because they notice that artistic labels are manipulated or concepts are inappropriately applied to familiar works. Market forces alone do not dominate the art world; the collective creative energy of artists is a powerful influence. Once it is diminished something like weeds, in art typically called schlock, proliferates. This does no one any good.

Quinn’s composite paintings on canvas and on paper are symbols of a tenacious spirit who refuses to deny his truth, in art that arises from unresolved emotions and fixed belief systems that have been established at a critical point in an impressionable age, without parental elucidation or support. The artist grew up in the Robert Taylor Homes on Chicago’s South Side which was then one of the nation’s most dangerous residences. In ninth grade he received a scholarship for the Culver Military Academy in Indiana. While away, his mother Mary died of a stroke. When he arrived back in Chicago for Thanksgiving, his dad and brother had abandoned their home. The artist determined to focus on his education rather than sinking into an existence of poverty. He has had a tough life, which has evidently spurred him to reach beyond the mundane, to spell out how such bitter life events can act as a life-transporting metamorphosis into an art of prodigious revelation.

Quinn expresses his pathos through the look in his subject’s eyes as well as in his bodily distortions. In sacred rituals African masks traditionally display animal features and body parts, to camouflage the bearer’s identity. In contrast, Quinn specifically intends to offer glimpses that evoke the trauma his life experiences have triggered. He likes to accent bulging muscular forms, suggesting time spent in the process of body building, that conceivably strengthen his emotional life as well. Quinn’s subjects stare out intently, as he discloses his heart and his inner life by putting viewers in touch with the suffering inherent in being human sans socially acceptable masks or protective psychic armor.

The artist has found a frank way to probe the depths of others in art that potentially inspires them to pursue their own truth. His foreshortened figures and fragmented features seem to function as metaphors for his jarring experiences. Unveiling these parts discloses residues of grief, in the effort to become whole. The intuitive paintings are rendered in powerful yet sensitively made forms, vibrant with brownish-pinks, saffron, citrus gone green, deep reds for lips, and dark brown but not black eyes. Quinn paints at a genuinely high level of focus apparently driven to perfection in order to create intricate passages in layered images.

This is the beauty of art; being in the moment without conscious thinking, the energy that drives the creative process concurrently reduces the tendency to resort to analytical thinking. This drive establishes inner and outer resolution powered not by thought, but by the unconscious creativity of our deepest level of being. By incorporating his mother in his works, he presumably brings her into his present state of mind and existence. Quinn explores his unconscious feelings and assumptions with their attendant angst by excavating the chunks of his experiences and relationships, with concentration so strong that a sense of safety and resolution can arise from the process. This level of dedicated initiative embodies the inspiration that hopefully reaches every viewer, including the artists among them.