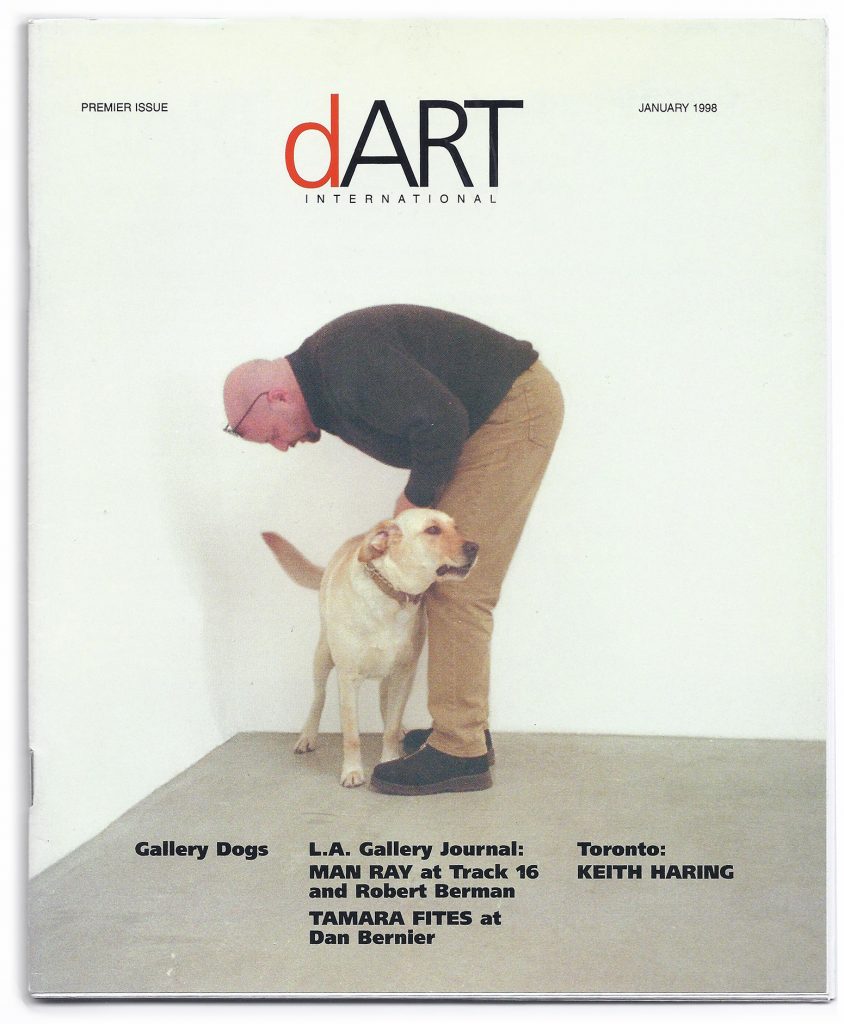

Gallery Dogs

An Affectionate Letter to Our Best Friend

Wolves and wild dogs, ancestors of the domesticated dog provide convenient models for the study of canine societies. Historically, in Europe and elsewhere, the wolf came to represent evil and licentiousness. It served as a template for nature’s baser instincts. When a girl loses her virginity in France, she has “seen the wolf.” Moreover, the wolves’ hunting skill are denigrated because they hunt in packs. The efficient kill is deemed cowardly when carried out by a gang.

Just as European societies feared and despised the wolf, the indigenous peoples of North America admired and emulated it. In the Old World the wolf was all but rubbed out, while many Indian tribes viewed the killing of a wolf as a bad omen. Their close identification with nature gave them an insight into the keen hunting skills of their canine cousins. Pack mentality was also good survival medicine in an often hostile world.

Recently, scientists have successfully infiltrated wolf colonies through imitative scent, vocalizations and food, and have found the wolves highly affectionate and considerate to one another. They even have what one could call a pension plan to care for those who are too old to take part in the hunt. Their food is shared.

Domestic dogs fit nicely into human society. They are genetically predisposed to hierarchies, ranking, and leaders. The cynical human view, of course, places the dog somewhere at the bottom. That’s not how the dog sees it. It’s about expediency, and they know that ranking is necessary for survival. They know instinctively where they are situated in people society. No domesticated animal accepts the role of the team player with as much fervor as the dog. It’s our best friend.

Guarding, herding, hunting, companionship, or whatever, the dog is there for us. Diana Smith from Tatistcheff/Rogers Gallery in Santa Monica said about Sparky, the dalmatian, “Sparky’s the general gallery dog. He does everything you ask him to do…”

Should we begrudge a little pampering for all those centuries of loyal service to humankind? Case in point: when Truman, Manny and Jackie Silverman’s wire-haired dachshund was denied his fluffing because the dog grooming truck broke down (and it’s not easy fluffing a wire-haired dachshund), he was deprived of something rightfully deserved. The transmission on the truck gave out, and it never got to the West Hollywood gallery. A dog is more reliable than a truck.

The effusiveness of the friendship with the beast often gives way to tawdriness. I suspect that the dog completely overlooks and forgives this because of its deep loyalty. Even in New York, Jackie Littlejohn’s Norwich terrier, Samantha, in her own dog way, winked at the little suggestive joke that came out of her name. Someone had called her Samantha Fox, and Jackie had liked the sound of the name. Two years later some said that it was the name of a porn queen.

At some distant point in the past, when the first wolves crossed over the line that divides animal society from human society, they had already evolved a highly developed intelligence. A wolf howl is audible over several miles, an instant and effective communications link. Wolf packs manage and control vast tracks of wilderness, through a sophisticated network of trails marked by their own scent.

This territorial instinct was expressed the first time that I visited the Regen Projects gallery in West Hollywood a couple of years ago. As I turned into the North Almont lane, the dog Gordo was already observing my approach. When I got there, Chip told me that “Gordo is like the symbol of the gallery. He’ll lick you to death.” Gordon jumped up on me. Chip said, “Down, Gordo, down…”

Man Ray in Hollywood

The January 1997 Exhibition at Track 16 and Robert Berman Galleries at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica

Man Ray in Hollywood 1940-1951 by Dickran Tashjian, edited by Pilar Perez. Introduction by Robert Berman and Tom Patchett. Published by Smart Art Press, Santa Monica CA 1996

When Man Ray arrived by boat in Hoboken, New Jersey on August 16, 1940, he felt dislocated and stressed from a rough ocean crossing. A previous attempt to escape by car from Paris had ended in failure. This time, his elation at having eluded the Nazis in France, according to Dickran Tashizian’s exhibition catalogue text, had been short-lived. Furthermore, when he arrived, he discovered that his camera equipment had been stolen.

Depressed, he couldn’t quite face staying in New York, and considered Tahiti as a destination. A family friend, Harry Kantor, persuaded Man Ray to accompany him to Los Angeles on a business trip. Setting out by car via Chicago, and catching Route 66, they arrived in Hollywood at night to searchlights sweeping the sky. The beams weren’t seeking out the Luftwaffe, and it might have been at this point, that he felt that an extended vacation was about to begin.

He didn’t entirely ignore the movie industry, being an avant-garde filmmaker himself, but he hated the idea of collaborating. Being “beyond the control of one,” it became a social effort, making it something else entirely. He also felt that the amount of time, money, and effort that went into making a movie was out of proportion with the result, a “distracted” public, “aroused” by “hopeless envies and desires.”

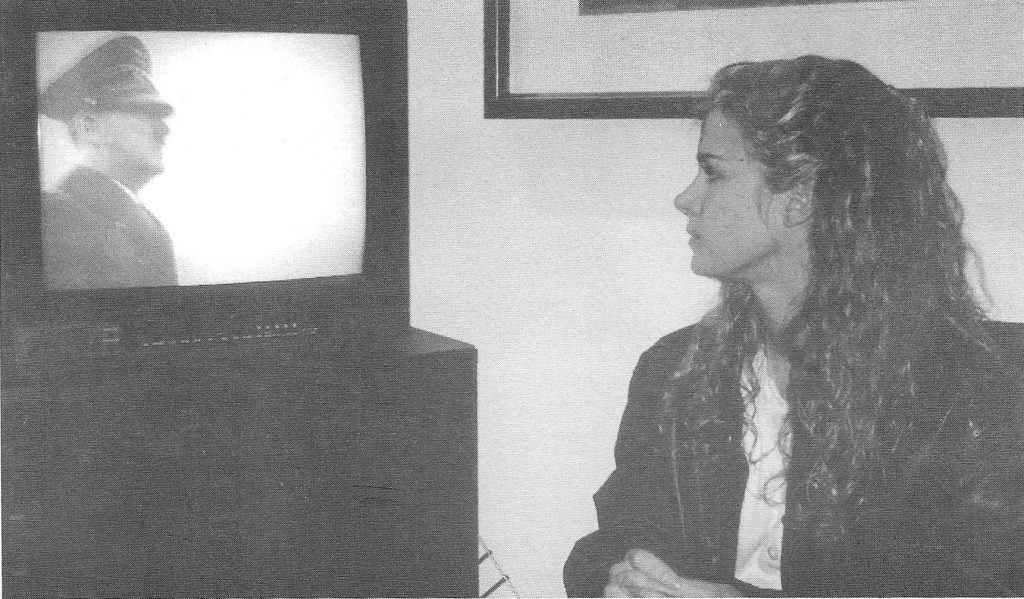

The centerpiece of the January 1997 Man Ray exhibition at Track 16 and Robert Berman Galleries was Le Beau Temps, a painting that held particular significance for Man Ray. Ironically titled, Fair Weather, it was in part a comment on the monstrous political climate in Europe at the outset of the war. A further irony was Man Ray’s repainting of it in smaller form after his arrival in sunny California.

Remaining in storage in Paris for decades, it became a cause for Robert Berman, in his effort through the Man Ray estate, to make it public. Its dramatic uncrossing became the subject of a documentary. When Le Beau Temps arrived from France for the exhibition, it came with a condition for its return if it didn’t sell. Negotiations with various American museums were unfruitful until the Philadelphia Museum of Art expressed an interest. A favorable French franc eventually facilitated the sale, and it sold for $1.87 million U.S. It now hangs in Philadelphia, Man Ray’s birthplace, next to a room devoted to Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray’s dear friend.