by Jonathan Goodman

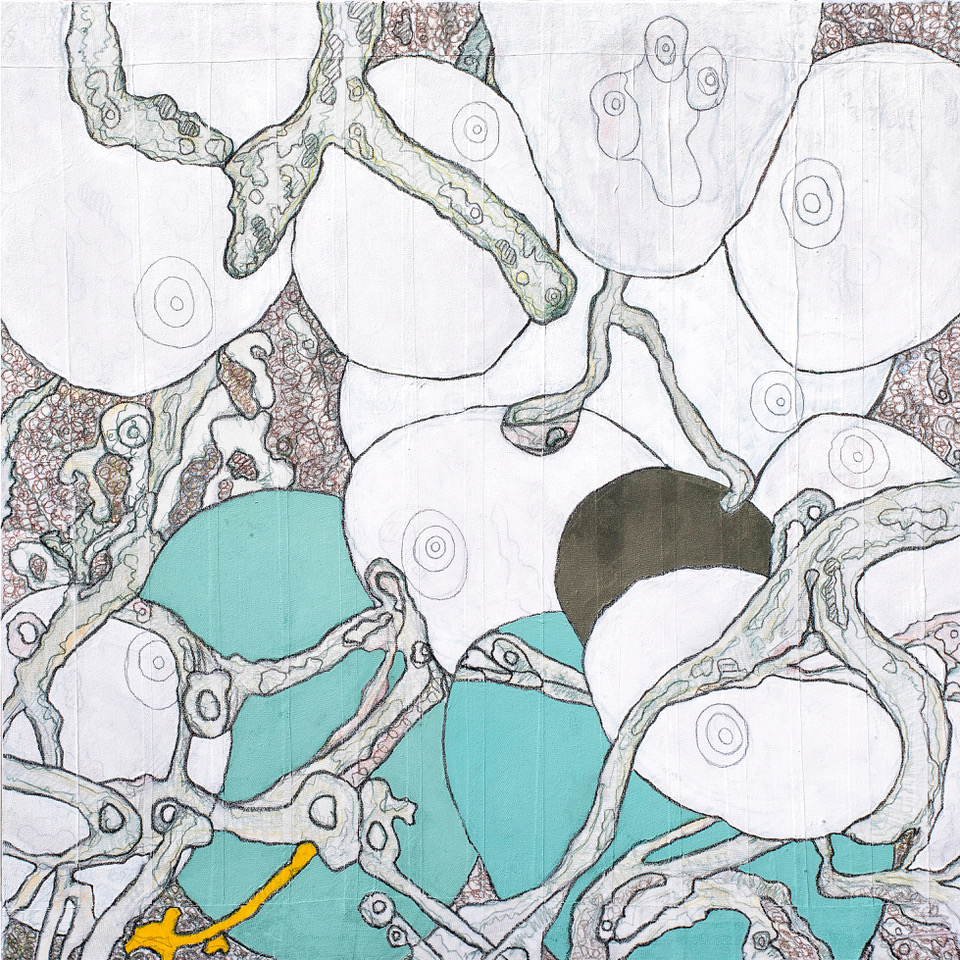

Costas Picadas comes from Greece, having been brought up in a family of doctors. But, eschewing that way of life, he decided to become an artist and studied in Paris before moving to New York City, where he now lives and works. A few years ago, his paintings were messy affairs, being taken up with dense overlays of rounded globular forms, much like the cells you might see in a microscope. Often, too, scribbles would make their way across the picture plane to the white sides framing the composition. The results were energetic and entertaining, as if the painting had forgotten its own boundaries.

But quite recently, Picadas has become a bit more restrained. His current works make use of similar drop-like forms, but the overlay of skeins of line is mostly gone. In consequence, the artist has moved more closely to classically defined abstract expressionism, an idiom so powerful it still effectively supports current efforts in the genre.

The ab-ex movement was enabled to a good extent by the efforts of foreign-born artists, and so Picadas is working within a decades-long tradition, It no longer makes sense to characterize this work as evidencing the original cultural influences on the artist practicing the style, Instead, the vernacular has become thoroughly international. The efflorescences of Picadas’s paintings are understood at once as joining the efforts of previous artists in New York.

Image courtesy of the artist

Yet there are differences, too. Remembering the medical background of Costas’s family, we can imagine his imagery as coming from pictures taken with a microscope’s magnification. The works are hardly compositions for doctors to study, but perhaps there is a trace of medical rigor to be found in the pictures. In the painting Biome 2 (2022), globules in white, with designs within them drawn in a very light gray, drift across the entire composition. They are painted on a grayish wall of bricks. In the lower part of the work, small splotches of black dot the areas between the globules accompanied by pale green, inchoate forms and even a single golden form. This piece surely looks like a slide of some foreign bacterium. The surface, which is busy, carries the interest, although we are unsure about a precise meaning beyond the dense arrangement of diverging shapes.. In Biomae 11 (2022), a black vertical column acts as the major support of the image, but light blue-gray lines, forming circles and rough, undefinable forms, cover the dark mass rising upward. Thinner lines adorn the sides of the column, whose brute force is softened by the embellishments.

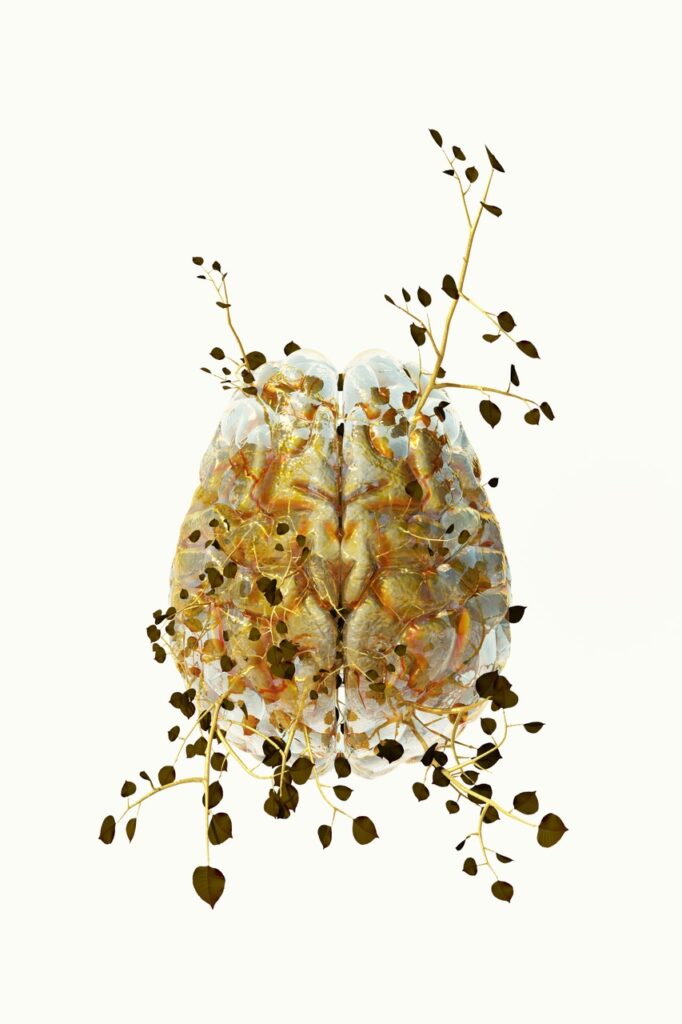

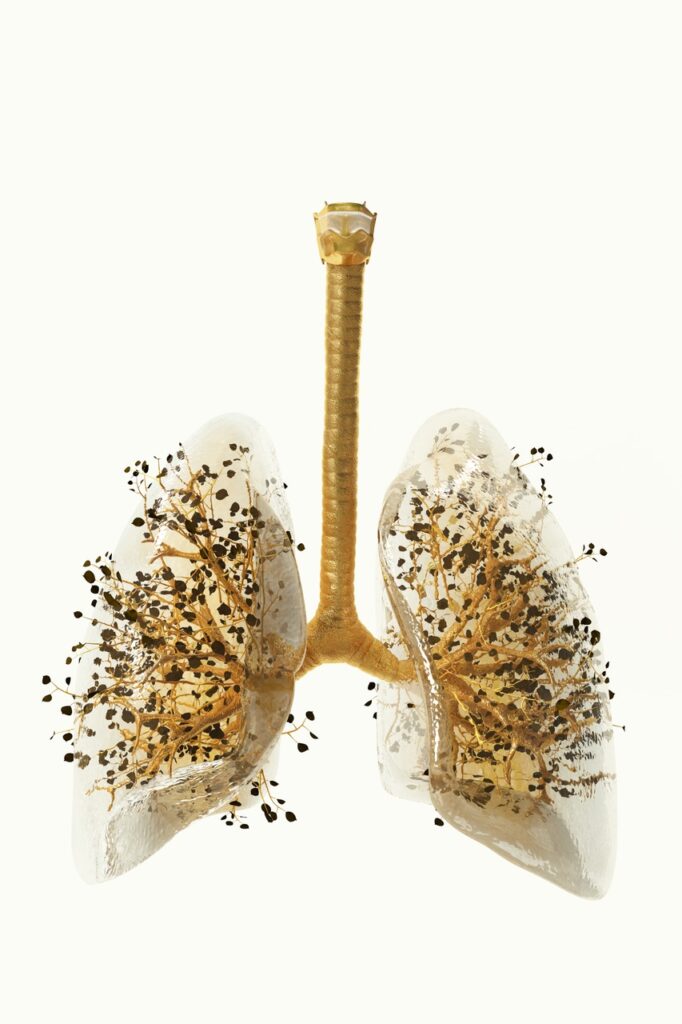

In a separate but strikingly effective group of works, Picadas uses a computer process to generate imagery closely aligned with the body and with nature. The work is small and figurative, but exquisitely detailed in ways that emphasize not only the overall gestalt, but also the sharp details. Lungs (YEAR?), Costas posts a highly detailed, highly realistic vision of the organs of breath: a trachea moves down the composition to split into two pipes, one each going to the semi-oval shape of each lung. Covering the lungs are small black blotches that combine with a tree-like maze of slender stems, ostensibly to carry the oxygen to the rest of the body. The graphic immediacy of the image astonishes; the sharpness of detail feels microscopic. In another image, called Heart (YEAR?), the reddish-brown semi-oval shape of a human heart anchors the thin stalks bearing black blossoms that rise from the upper surface of the organ. Here anatomy meets the lyrical bent of nature, and both appear enhanced by the affiliation.

Picadas’s art reverses our expectations by merging the intuitions of the process, its justifications as an interpretation of what we see, with the much more stringent detailing of natural (or scientific) imaging. In his case, the merger makes sense in that he comes from a family whose vocation was scientific in nature. By softening his effects a bit, Picadas mkes it clear that the scientific methods contribute well to a view most effectively disposed toward painting, rather than to the rigors of the lab. Picadas uses his background well, but medicine never overtakes his pictorial intelligence. We can conclude that the painter’s merger, between cellular depiction and free-wheeling abstraction, consistently results in compelling art.