by Gary Michael Dault

All the good things that can be said about a painter have been said about Alex Cameron. Which is not to say that they ought not be said again and again and again. Especially now, after his grievous and entirely unexpected death from a serious fall not far from his Toronto studio last June 17. He was seventy-eight years old.

Much will rightly be said, now and in the future, about Cameron’s pauseless exuberance, about his adventurousness: about his working as a studio assistant to the legendary Jack Bush, about his serving for over a decade as a mechanic for champion Formula 1 and 2 motorcycle racer, Miles Baldwin, about his intrepid voyaging into the wildernesses of Northern Canada and Western Canada, of India and Nepal. Fearless and dashing stuff.

But while there is a lot to recount about Alex Cameron’s searching, expansive life—as an explorer in a tireless pursuit of colour and vista, form and transcendence—I just can’t bring myself to rehearse much of that bio-stuff here and now. Others will supply all that. For me, all I can think of right now is Alex Cameron and paint, Alex and the utter rapturousness of pigment. The Alex Cameron in my heart right now is the Alex Cameron who once explained to some interviewer that he saw his skies as “colour fields,” noting that he liked having skies in his paintings so that he could “stick stuff in them.” “Stuff” being paint.

I once began a catalogue essay for a Cameron exhibition at Toronto’s Moore Galley called (unhappily, I thought), “2001—A Paint Odyssey” (the Kubrick film had just come out), with a paragraph that I hoped simultaneously introduced and also summarized the kind of painter I felt Cameron was (and was still becoming): “Alex Cameron’s paintings,” I wrote, “are immensely, winningly genial. There is a painterly robustness about them that is remarkably infectious. And while this by no means denies them aesthetic ambition, it does mean that their seriousness lies behind and within the artist’s love of painting for its own sake. To look at a Cameron, to open yourself to one, means there is a good deal of joy to be got through before you come to the core of it—an onerous enough task in the generally repressed hedonism-wary times in which we live” (clearly nothing much has changed over the past quarter century).

The Cameron paintings I was writing about around this time (2000-2007) were usually large, airy, non-representational works which tended to be made up of painterly dots and swipes, flanges and rinds of colour, feathery sweeps of the brush over his gala surfaces, and a recourse to very hot, strident hues (plummy violets were big with Alex, I remember, and oxidized yellows and roasted tomato reds). Sometimes parts of the canvases were sprayed. I remember being a bit discomfited, though, when The Globe & Mail titled one of my full-tilt articles about Alex (April 21, 2007) “Fauvist Fandango” (newspaper writers do not get to title their own pieces).

In a discussion of a big oil painting called “Gabriell’s Wings” from 2001 that I wrote about for the Moore Gallery, I noted that Alex was “A skilled landscape painter when he chose to be (his idea of a good tine is to be helicoptered into the wilderness and set down amongst the bears and beavers to paint the solitude). Cameron,” I continued, “builds his abstractions on a firm footing of landscape-derived shapes—a bright swatch of lake-like horizontality across the bottom of a painting, above which a cheeky, serpentine wobble of pigment, an echo of a far shore, softens you up for entry into the aerial ballet taking place up in the rest of the picture.” I spoke of the “electric agitation” of his pictures. And I made admiring mention of the way Alex would smear paint onto his surfaces with his fingers or “let fly with it so that the deep space of the paintings is galvanized by infinitely small threads and hot wires of pigment—tiny, shrill utterances of hue.”

Eventually, inevitably, the Landscape-Idea shouldered its way decisively forward, informing the stream of vigorous, muscular landscape paintings that would now preoccupy him for the rest of his career.

And remarkable landscapes they always were. Alex gloried in the untouched forest and, in painting after painting, became its scribe, anthologist and, to some degree, its archivist. This latter tendency actually used to give me pause sometimes. The fact is, Alex painted trees so vividly and convincingly they were themselves—or so I thought—beginning to encroach, as an almost documentary subject, upon the progress of his painting qua painting.

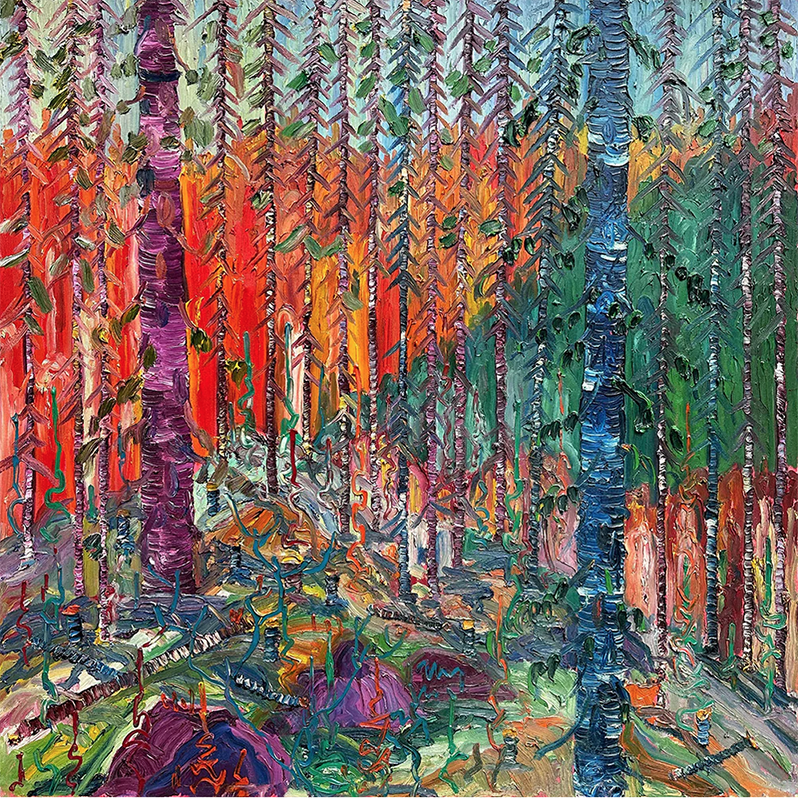

Alex seemed to sense this himself. And he gradually began throttling up the paintings so that the contretemps between his beloved subject (trees) and his handling of them (in daring acts of pigment) turned increasingly into a virtuoso tussle than a dutiful homage.

Which is to say that just when the paintings were on the edge of becoming too nakedly arboreal, Alex began using the trees—the forest skyline—as his armature upon which to drape and generally festoon his increasingly writhing and tumultuous attacks of pigment. The artist’s forest increasingly became trees, not as they could be taxonomically described, but as they were felt—as purely visual objects in a scintillating visual field, as gloriously life-enhancing vectors thrusting up into the painterly light.

It strikes me that these descriptions of Alex’s excitingly lush and scrappy production of big sinewy wilderness paintings might position him, in the minds of people who didn’t know him, as a big, brawny, rather Paul Bunyan-esque figure, bestriding the waiting landscape like a colossus. The truth is, Alex was a slight, tensile, quick and rather elfin man—with a boyish grin so infectious it was almost impossible not to see something leprechaunish in him.

While this enjoyable, mercurial joie-de-vivre was a sort of admirable constant in Alex’s life, he endured a number of distressing medical events which might well have stilled and silenced a less perpetually resilient man. I remember an afternoon in which painter David Bolduc—Alex’s best friend and mine too—and I were chatting at a Toronto coffee shop we liked called Il Gatto Nero (it was maybe 2007 or 2008) when Alex came to join us. I remember how, during one gregarious moment, he causally mentioned that he had just suffered a slight stroke which had left him with a strange floating rectangle of pure white blocking his eye—I think it was his right eye. David and I were distressed, but Alex gave us the impression that he would simply soldier cheerfully on, seeing the world around this intrusive white spot. I can’t recall his ever mentioning it again. Then, in 2012, he suffered a much more serious stroke which left him entirely unable to use his right arm. Anyone else might have given up painting in despair. Alex being Alex, however, he simply set about learning how to paint with his left arm alone.

Not only did this would-be deprivation not appear to alter or diminish Alex’s progress as a painter, the paintings he would make from 2012 until his death this year would be the most brawny, restless, opulent and downright ecstatic of his career. His trees and lakes commingled exuberantly with his clouds and skies until each of his canvases shuddered and heaved with convulsive, painterly life. These later canvases grabbed you by the lapel and shook you until your sensibility rattled.

Look at a painting like My Dad’s Forest (2015) or the exquisite Colours (also from 2015). Pictures like these offer—just as a technical feat—the best, most virtuoso paint-handling I’ve seen in Canadian painting for decades. Look hard at them and your eyes will never be the same.

The late Camerons are not so much landscapes as paintscapes. If the wilderness is in peril (and when is it not?), then Alex Cameron would try to brush it back to life.

He loved to paint. And now his paintings will live for him.