by Chunbum Park

Allan Rand’s solo exhibition titled, “Transportation,” at YveYang is an earnest exploration of painting in all of its conceptual, material, and formal dimensions. How does Rand treat painting as a material and aesthetic object rather than an illustrational endeavor? This is a body of work, which Rand began as he researched the subjects sent to the penal colony of Australia, where he currently lives (he is from Denmark). The artist exhibits an ideological affinity for egalitarian and progressive thought that questions the state power and the oppressive nature of the law by the nature of its uniformity.

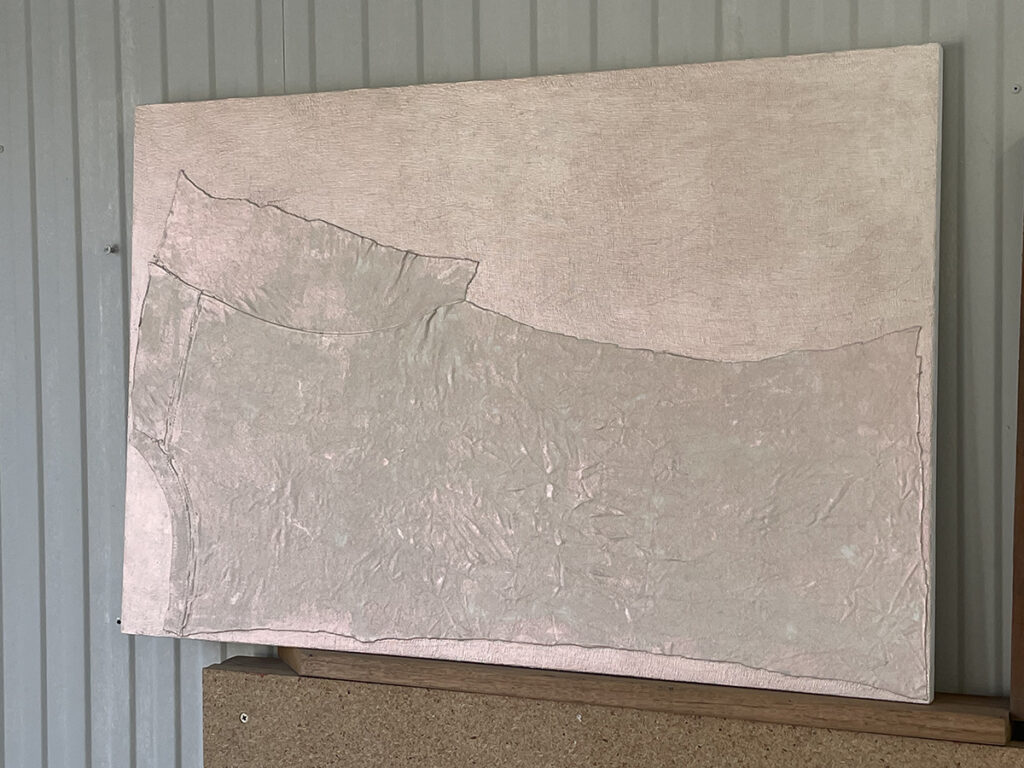

To an uninformed eye, “Icon for Safe Passage across the Seas” (2025) could be literally seen as a t-shirt fragment pasted onto a cotton stretched onto a wooden board. However, the work expands the material vocabulary, substituting the large brush work with the pasting of the fabric, which then becomes this wide expanse of a turbulent sea. The use of iridescent medium invokes the mysterious quality of the light of the celestial bodies visible in the night sky (perhaps within the eye of a hurricane or typhoon), as in J. M. W. Turner’s paintings. The work is very much a post-minimalist type that asks the viewer to give more in order to receive. It neither illustrates nor gives in a literal fashion; the work is highly abstract and minimal, asking the viewer to settle into the quietness of the painting and to ask questions within a slow, meditational-style state of mind.

What are we looking at? Is this representational or abstract, or both? Is this a cropping of a life-sized portrait or a scene cut from an expansive landscape? Are the colors staying consistent, or are they flipping between warm and cool colors, and what does this mean for the painting? The use of abalone shell glitter alongside the iridescent paint material is highly symbolic, conjuring up the idea or the metaphor of a defensive shell that protects a treasure-like core. Furthermore, the flipping of hues suggests the artist’s inclination to seek freedom and to resist conformity or uniformity. A lot is being said, and a great deal needs to be heard, despite the silent nature of this painting.

A favorite in the show could be “Stoop Culture (for B.B.)” (2025), which the artist began off a story that he had heard of a building in the West Village of Manhattan that had its front facade fall off during a hurricane. Rand also heard stories of a demi-monde badger game taking place in another building, where extortionists had men lured by women into having sexual intercourse with them and then exposed the men through the setup by kicking down the door (and entering at the moment of climax). Rand’s work does not involve illustration in a literal fashion, but combines the two buildings into an atemporal archetype that stands outside a particular reference to a time within a linear or historical timeline. The narrative elements manifest as lines of charcoal, gently colored with passionate, rosy, and warm pinks and hot burnt siennas, some of which are made with ground-up bricks that originate from the Australian prisons.

This is the contradiction of Rand’s work – he positions the criminal figures in the story as the protagonists , like the movie “Ocean’s Eleven,” rather than automatically condemning them. This tendency of Rand’s to question the uniform requirement of the law, for everyone to obey the law and to not question it, could serve as a healthy dose of counter narrative or non-conformity against easy condemnation and judgment. Similar to how Philip Guston tried to understand the KKK by depicting himself as one, Rand feels the need to investigate the inner workings of the criminal mindset and psyche and thereby positions them within his own imaginative framework as the protagonists and the self. It is akin to method acting, in which the artist positions himself as true to the roles of his story, whether they are the “good” or “bad” characters.

It is this flipping of color, value, or perspective, which gives us the hint that Rand’s art is actively trying to understand… He is attempting to comprehend criminality in relation to the law and the subjectivity of the criminals. This understanding for the criminals involves the psychological, and the qualitative and quantitative complexity of and the subjective reasons for the criminal acts and the subjecthood of the criminals themselves. The complexity could manifest as a graph or a spectrum (in terms of the degree and the nature of the crime, whether petty or severe, and the person’s situational difficulty). (The law would be Procrustean if it treated petty and severe crimes with similar or same sentencing beyond the seas.)

What is justice if we are not allowed to question and challenge it? The bedrock for Rand is the need to understand the subjectivity and the shared humanity… or the need to respect criminals as human beings, despite their denigrated status and their denied humanity. This is the kind of painting and the accompanying dialogue that we should all learn to appreciate, despite their demanding nature… which requires bravery and honesty from us for ourselves… for the sake of truth, whichever that may be.