by Robert Egert

Carol Bruns’s work first caught my attention in 2018 at SRO gallery in Crown Heights. Her exhibition showcased a mix of sculpture and works on paper. Her figurative sculptures conveyed the presence of human bodies in space, twisting, straining to emerge from their own materiality. Despite the rough construction and exaggerated physicality of those figures, one could still discern vestiges of humanist dynamics or perhaps a loose tether to drawing or sculpting directly from a nude model.

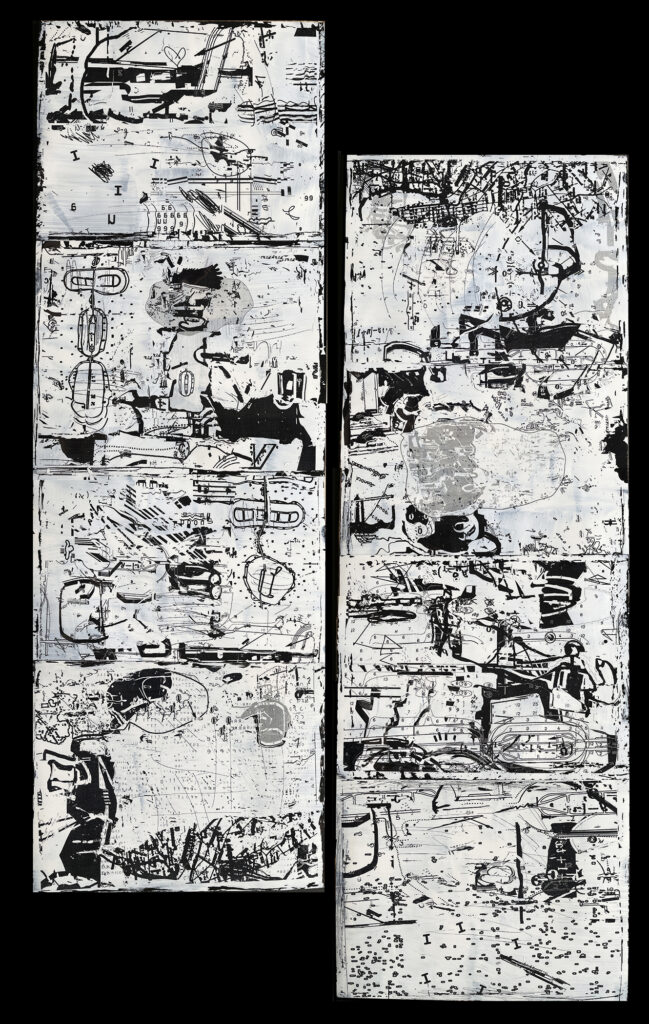

In her new, expansive show at White Columns, Bruns has departed entirely from the figurative tradition and embraced a kind of archaic, mythic approach. The gallery is filled with oversized masks, slender stacked totems, and distorted effigies. While these figures and heads still seem to struggle to emerge from the process of their making, once emerged they say less about the figure and more about the psyche.

As is true for many sculptors, materiality and process cannot be taken for granted, and Bruns has developed a unique process over several years. Her approach produces a papier mâché-like material that is thinner, lighter, and more malleable. It’s flexible enough for her to incorporate other materials such as hair, fibers, plant matter, and Styrofoam. The pieces are predominately painted in monochrome black or white, adding to their stark, confrontational presence while unifying the disparate elements. The final effect is disarmingly fresh, unpretentious, and incredibly present.

A cursory viewing evokes the art of West Africa, Polynesia and other pre-industrial cultures, including archaic Greece. While those connections to the art of past are clear, these pieces go beyond homage or derivation, for the clear influence of psychology and contemporary ideas about the self that are immanent in the work. Bruns cites early twentieth century modernists as an inspiration, in addition to the original, unnamed artists that inspired them, but her work is firmly rooted in the twenty-first century.

Every artist begins with intentions, and for Bruns I suspect the intention is to evoke mythos, to mine the archetypal psyche, to connect with the root forces and human experience that unites us simultaneously to pre-industrial, tribal artists as well as the early twentieth century modernists who referenced them. But, despite all intentions, none of us can help but be mediums for the zeitgeist, and the same is true for Bruns, whose work channels our contemporary state of being, clinging to individuality, polluted by industrialization, and disenfranchised by the post-industrial economy.

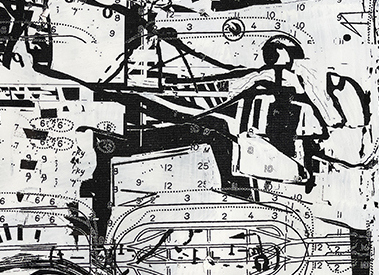

Consider Archaic Man, whose title and direct advancing aspect forces us to consider it relative to the Greek Kouros. We can take this to be a representation of a God in human form but unlike the ancient ones, this is one infiltrated by industrial elements. The classic forward stride of the Kouros is replaced by found objects stacked to an absurd approximation of an articulate leg, rendering a figure that one would more likely associate with having survived a terrible accident than a God descending from Mount Olympus.

Or Seeing in the Dark, which speaks to subjective, interior truth dissociated from shared sensory perception. Here’s a figure that is so totally inwardly focused that their sensory organs have essentially been swallowed back into the head, a totally modern idea that assigns priority to individual, subjective experience over shared truth.

The White Columns’ exhibition alternates free-standing totems, wall-hung objects, and pedestal-mounted head-like figures. This installation approach emphasizes variety and contrast among Bruns’s work and highlights subtleties among the pieces. This enables us to read the emotional and mental states depicted: Faces that appear crushed, silenced, or occluded, reduced to a mere gash for a mouth or two small holes for eyes. In these pieces the subject is always the interior self while the form is the distorted, tortured body.

Bruns selectively employs a non-transformative approach to materials, often incorporating recognizable found objects like Styrofoam packing into her work. This suggests a fluid connection between cultural vocabularies and expectations. Unlike her earlier work that maintained ties to traditional representation of the human body, Bruns’s new creations invest in the ability of myth and cultic power to transform materials as opposed to representation. Bruns is tapping into the realm of expression that flirts with primordial and introspective emotional states that don’t easily translate into language, evoking at once a sense of ancient mysticism, ritualistic power and contemporary psychology. Her pieces resonate with traditional objects from the distant past, yet they remain palpably contemporary and enigmatic.

Carol Bruns’s exhibition at White Columns serves as an invitation to explore the intersection of ancient symbolism with contemporary concepts of self. Her pieces remind us of the enduring potency of myth and ritual, while mining the contradictions of the contemporary psyche.

Carol Bruns at White Columns from July 13 – August 26, 2023. White Columns, 91 Horatio Street, New York, NY 10014. Tuesday–Saturday, 11AM–6 PM.