by Roy Bernardi

The art world is a realm where new discoveries occur on a daily basis. While some may argue that finding a life-changing bargain is improbable, the reality is that such opportunities do exist, often emerging unexpectedly. Artworks are unearthed regularly in the most surprising locations. One must simply open their eyes and comprehend what they are observing.

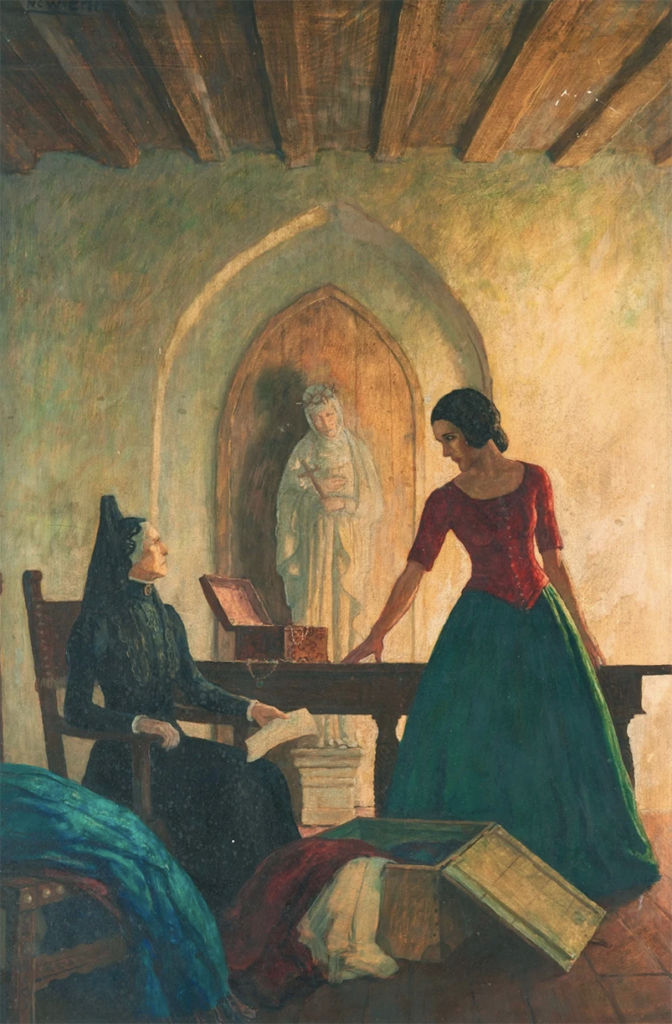

N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945). A woman bought a painting measuring 25-1/8 x 16-7/8 inches in a frame 28 x 19-1/2 inches for $4 at a thrift store, primarily for its frame. This was the aspiration of a woman as she rummaged through a collection of old frames during her visit to Savers, a thrift store located in New Hampshire. This situation highlights the notion that a frame can sometimes be more valuable than the artwork it holds. Only to later learn that the painting within the frame was an N.C. Wyeth original artwork valued at around $150,000 to $250,000 USD. The identification of the painting as the work of the esteemed American painter and illustrator N.C. Wyeth was facilitated by an art conservator based in Maine.

The American painter, whose life spanned from 1882 to 1945, had an extensive career that included creating illustrations for magazines and authors over several decades. The painting found in a thrift store has been identified as one of four potential cover designs for the 1939 edition of Helen Hunt Jackson’s novel, Ramona. This story follows the life of a fictional girl of mixed Scottish and Native American heritage, who is left orphaned shortly after the Mexican-American War concluded in 1848. In this piece, Wyeth illustrates a critical moment in the story, where Ramona adopts a defiant posture in front of her adoptive mother, Señora Moreno, whose chilly disposition is effectively represented by her stark black dress.

The details regarding how this artwork came to be in a New Hampshire thrift shop are still unknown. The painting was eventually sold 19 September 2023 for $191,000 USD at Bonhams Skinner Auctions in Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669). The painting titled The Adoration of The Kings, an oil on oak panel measuring 24.5 x 18.5 cm (9-5/8 x 7-1/4 inches), created circa 1628 which possesses a distinctive provenance that traces back to Amsterdam. It was first recorded in an estate inventory sale on 17 May 1715, listed as lot 1. Subsequently, it was sold in London at Phillips on 2 June 1814, listed as lot 40, where it fetched 215 Guineas. The artwork was later presented for sale again in London at Phillips on 29 June 1822, identified as “by” Rembrandt van Rijn, under the title The Adoration of the Magi. On 27 March 1963, it was auctioned at Sotheby’s in London listed as lot 13, as “by” Rembrandt van Rijn, but went unsold at £3,800. The piece was eventually sold in Amsterdam at Christie’s on 3 December 1985, cataloged as “Circle of” Rembrandt van Rijn. It reappeared at an online auction at Christie’s in Amsterdam on 6 October 2021, listed as lot 7, also attributed to “Circle of” Rembrandt van Rijn, with an estimated value of 10,000-15,000 EUR, ultimately achieving a sale price of 860,000 EUR. The auction house catalogued it as a work from the “circle of” Rembrandt however the interest shown in the bidding indicated that several bidders suspected it might truly be a creation of the Old Master.

Following a thorough analysis that incorporated infrared and x-ray imaging, along with evaluations by prominent Rembrandt scholars, experts have reattributed the small Biblical painting, which had been absent from historical records for many years, to Rembrandt van Rijn. The characteristics typical of his late 1620s style are apparent in both the visible painted surface and the underlying layers uncovered through scientific methods, revealing numerous alterations made during its creation and providing new insights into his artistic process.

Sotheby’s has confirmed that the artwork is indeed an authentic Rembrandt. It was featured in the auction house’s evening sale of Old Masters and 19th Century Paintings listed as lot 11, held in London on 6 December 2023, with an estimated value ranging from 10,000,000 to 15,000,000 GBP. Ultimately, the piece was sold for a final bid price of 10,965,300 GBP.

Giorgio da Castelfranco (Giorgione) (1473/74–1510). A remarkable discovery has been made by an interdisciplinary team of scholars and scientists at the Alte Pinakothek and the Doerner Institute in Munich, Germany. Comprehensive art-historical and art-technological studies, undertaken as part of a research initiative focused on the Venetian Renaissance paintings within the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen (Bavarian State Painting Collections), have validated the insights that began to surface during the exhibition ‘Venezia 500 The Gentle Revolution of Venetian Painting’ from October 2023 to February 2024.

The enigmatic double portrait, titled Portrait of Giovanni Borgherini and Trifone Gabriele, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 67 cm (36 x 26-1/4 inches) painted in 1509/10 previously showcased at the Grüne Galerie in the Munich Residenz since 2011 and currently housed in the Alte Pinakothek, has been ascribed to Giorgio da Castelfranco, commonly referred to as Giorgione.

Giorgione, an influential Italian painter of the Venetian school during the High Renaissance, died in 1510 at a young age in his thirties. Originating from the quaint town of Castelfranco Veneto, which is also the birthplace of my father, Peter Bernardi, who was born in 1935. The town is situated 40 kilometers inland from Venice. An important milestone in Giorgione’s life was his encounter with Leonardo da Vinci in the year 1500. Giorgione is celebrated for the elusive and poetic nature of his artwork. However, only a limited number of paintings can be definitively attributed to him. The ambiguity surrounding the identity and interpretation of his pieces has rendered Giorgione one of the most enigmatic figures in European art history. He is widely regarded as the first Italian to incorporate landscapes as a background for figures in his paintings. In addition to altarpieces and portraits, he created works that lacked a narrative, whether biblical or classical, focusing instead on conveying moods of lyrical or romantic sentiment through form and colour.

This attribution positions it among the rare known works of this remarkably gifted artist, whose brief career significantly transformed Renaissance painting. The research results, represent a remarkable breakthrough in the study of Italian Renaissance art.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653). The Kimbell Art Museum, located in Fort Worth, Texas, USA, has acquired a significant work by Artemisia Gentileschi. This painting is believed to be the original of a composition that has been replicated in several copies, a masterpiece once thought to be lost. Numerous reproductions of this artwork exist, including one that was auctioned in Genoa at Cambi Auction House on 30 June 2020. This particular copy, Lot 121 listed as “After” Artemisia Gentileschi, had an estimated value of 5,000-6,000 EUR but ultimately sold for 47,500 EUR.

For years, scholars have been in pursuit of this artwork, which had been thought to be lost. The painting titled Penitent Mary Magdalene circa 1625-1626, oil on canvas, 109.22 x 93.98 cm (43 x 37 inches) was first acquired, by Fernando Enríquez Afán de Ribera, the third duke of Alcalá and viceroy of Naples, during his role as the Spanish ambassador to Rome from 1625 to 1626. It was believed in the 18th century that the duke might have commissioned Artemisia, as indicated by the references to the painting in the inventories of his collection. The painting was later displayed in his Seville home, the Casa de Pilatos, where it became renowned and was widely reproduced.

Following the passing of the Duke of Alcalá, the painting was retained by his heirs in Seville until it vanished completely. It resurfaced at Tajan Auction House Old Master Paintings sale in France 19 December 2001, Lot 7, where it was attributed to the “studio/workshop” of Artemisia Gentileschi. Bidders, under the impression that it was an original creation, ultimately purchased it for $206,441, a figure that greatly exceeded the high estimate of $11,000. Artemisia’s artwork has achieved sales figures reaching as high as $5,259,897 USD. Subsequently, it was acquired by a private collection and remained there until Adam Williams Fine Art Ltd. of New York purchased it on behalf of the Kimbell Art Museum in 2024. The artwork is displayed in the section of the museum dedicated to showcasing other masterpieces of early 17th-century Italian painting, alongside renowned works such as Caravaggio’s The Bari (circa 1595) and Guercino’s Christ and the Samaritan Woman (circa 1619-1620).

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (Il Guercino) (1591-1666). An oil on canvas painting depicting Moses, and measuring 72 x 63 cm (28-1/4 x 24-3/4 inches), was consigned to a sale held at Hôtel Drouot in Paris 25 November 2022, which was organized by the Paris auction house Chayette & Cheval. At that time, the artwork was attributed to an unidentified “follower’ of Guido Reni from the 17th-century Bolognese school, with an estimated value ranging from €5,000 to €6,000.The catalogue of Chayette & Cheval indicated that the auction house had contemplated attributing the work to Guercino, citing the fact that a replica of the same composition by his student Benedetto Zalone was presented by the Franco Semenzato auction house in Venice in 2001. However, the catalogue did not disclose the reasons for dismissing this evidence.

The artwork evidently attracted the discerning attention of at least two bidders, who engaged in a competitive auction. Ultimately, an Italian Old Master expert emerged victorious, securing the piece for an impressive €590,000. However, this amount pales in comparison to the painting’s true worth, which is estimated to be around €2 million.

Over the following year, the astute dealer commenced the process of restoring the painting and verifying its provenance. After months of careful examination, experts announced that the newly discovered painting was actually completed bythe Italian Baroque master Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, better known as Il Guercino. A measured risk was undertaken, as acquiring a painting in a dirty condition inherently carries a degree of uncertainty.

Recent studies indicate that this artwork was created circa 1618 or 1619, during Guercino’s late twenties while he resided in Cento, near Bologna. This timeframe positions it as a quintessential representation of the artist’s esteemed prima maniera, a term that refers to the pieces he crafted prior to his relocation to Rome in 1621.

The painting of Moses was initially part of the esteemed collection belonging to Cardinal Alessandro d’Este in Rome. Following his passing in 1624, it remained within his family. It is believed that during the years 1796-97, the painting was likely seized by Napoleon’s troops in Modena and transported to France.

Guercino’s depiction of Moses has been purchased by the charitable foundation of Jacob Rothschild. The painting is set to be permanently showcased at Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, managed by the Rothschild Foundation on behalf of the National Trust.

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641). An Anthony van Dyck painting, titled A Study for Saint Jerome, has been rediscovered. This oil on canvas piece measures 95 by 58.5 cm (37½ by 23 inches) and was previously left in a dilapidated state in a farm shed located in Kinderhook, New York. It was acquired for a mere $600 USD. It was not until after the collector’s death in 2021 that his family opted to auction the piece, at which point it was identified as a Van Dyck.

The portrait depicts a nude man sitting on a stool and was likely painted between 1615 and 1618 when Van Dyck was working with Peter Paul Rubens in Antwerp. This piece serves as a study for a subsequent work by the Flemish master titled St. Jerome. The completed painting is currently housed in the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam.

The artwork was offered for sale at Sotheby’s Old Master Painting auction in New York on 26 January 2023, listed as Lot 110, with an estimated value of $2,000,000 to $3,000,000 USD, ultimately selling for $3,075,000 USD.