by Chunbum Park

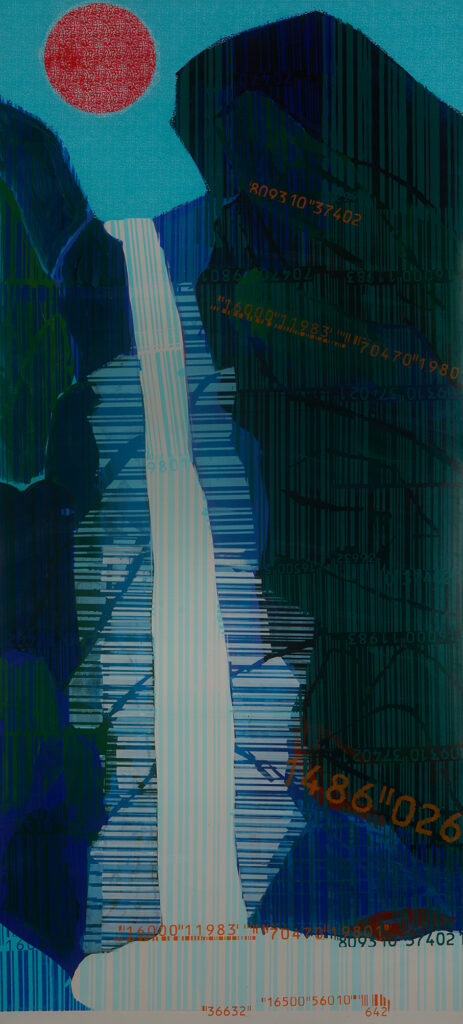

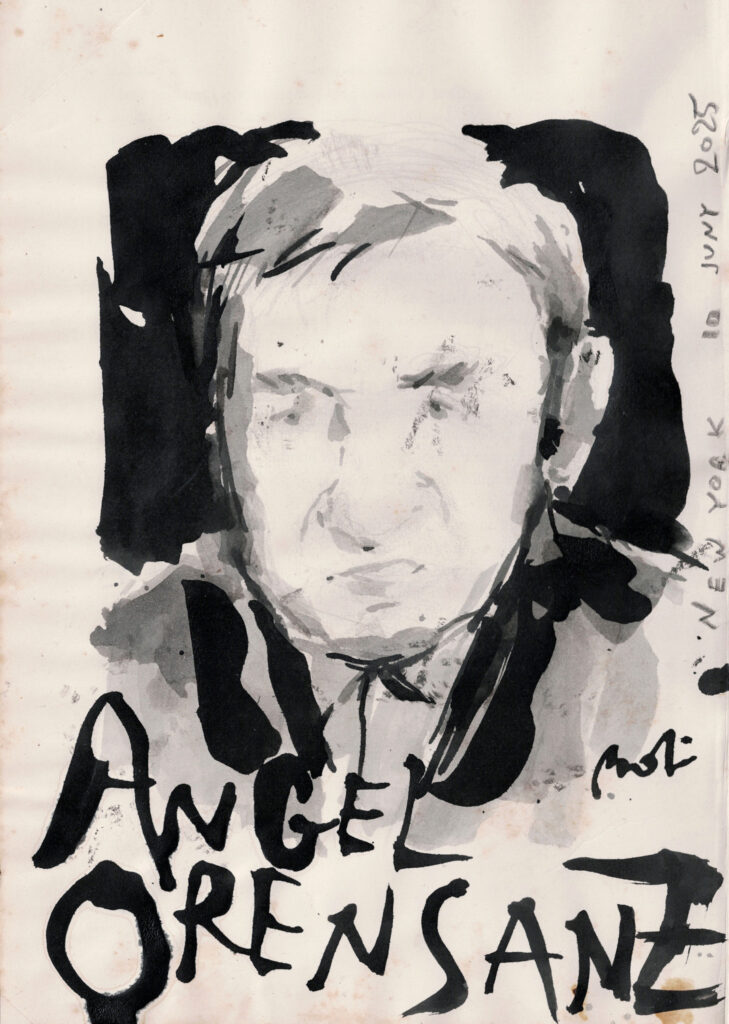

Joan Bofill, a Spanish visual artist and filmmaker, engages with a mode of portraiture which he calls “Double Portrait,” to capture a meaningful trace and record of his encounters with distinguished figures. At the Angel Orensanz Foundation’s gothic synagogue, Bofill’s exhibition, “Double Portrait: Paintings In Conversation” (October 16-17), takes place in collaboration with (Director) Sozita Goudouna’s The Opening Gallery. The Angel Orensanz Foundation for the Arts, established 1992 in New York City, is an artistic and cultural space/institution open to artists, writers, thinkers and leaders, including Philip Glass and Spike Lee; Arthur Miller, Alexander McQueen, Salman Rushdie, Maya Angelou and Alexander Borovsky; Elie Wiesel and Chuck Close. The current show brings together both large-scale paintings and the smaller “Double Portraits.” The “Double Portrait” project specifically involves both the filming of the encounter or interview and the artist’s drawing/painting of the figure with India ink and graphite. The series emerged from his documentary work, particularly his film about Hollywood producer Stuart Cornfeld (premiering at AFI Festival October 23). While conducting interviews for that film, Bofill began drawing his subjects simultaneously—a practice that evolved into something more deliberate.

“Double Portrait” is a synthetic process with dialogue based on mutual trust and the dynamic interplay of personalities – the artist’s and the interviewee’s. The artist envisions the “Double Portrait” as a principled endeavor – one that refuses to exploit or use people for their fame and which happens naturally and organically through a web or network of human connections. Throughout the continuation of this practice, Stuart Cornfield might introduce another filmmaker like David Lynch to the artist purely out of delight for the conversation that the artist engaged in with the person.

The manner in which Bofill tunes into the conversation with the figures with an observant, creative, and informed mind gains the trust of the interviewees, which allows them to open up to the artist to create together a playful and friendly synthesis of ideas, not necessarily as thesis and antithesis, but as intuition embracing intuitions, and experience empathizing with experience.

All the information garnered by the artist feeds into the artist’s psyche in interpreting and digesting the subject’s persona and history, which contributes to the final image through the subconscious.

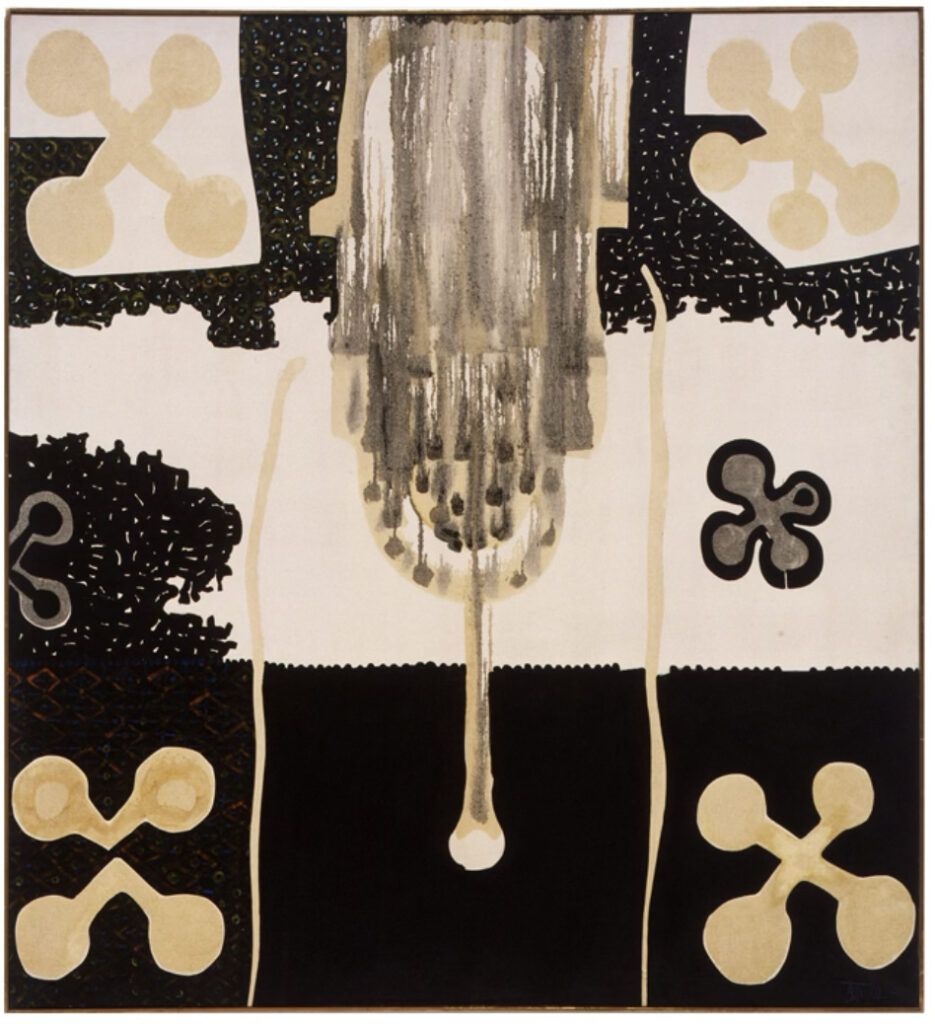

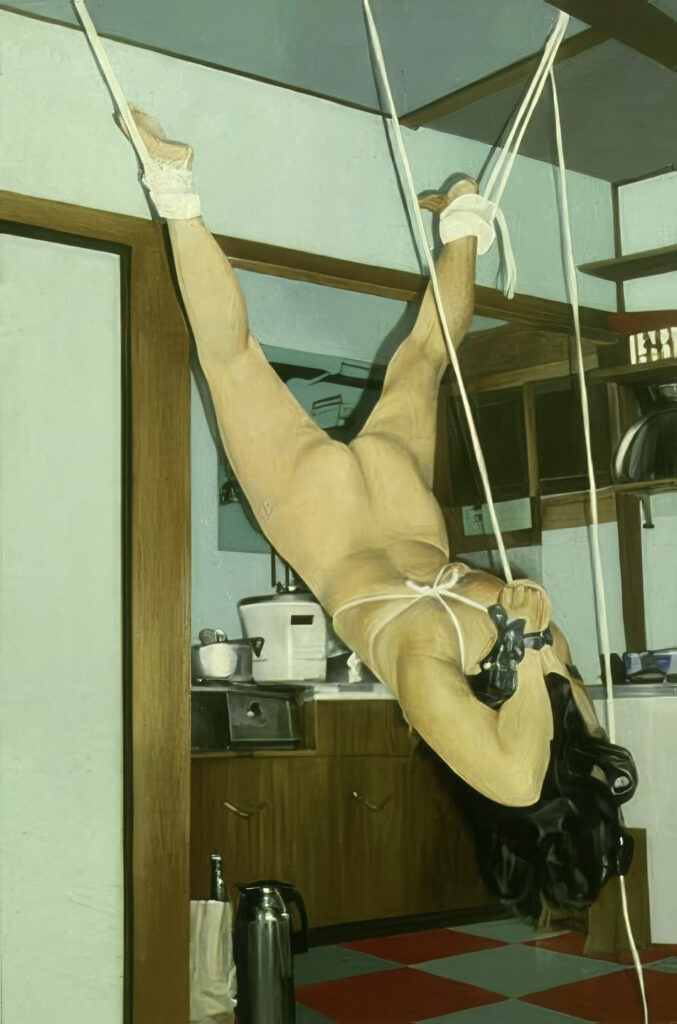

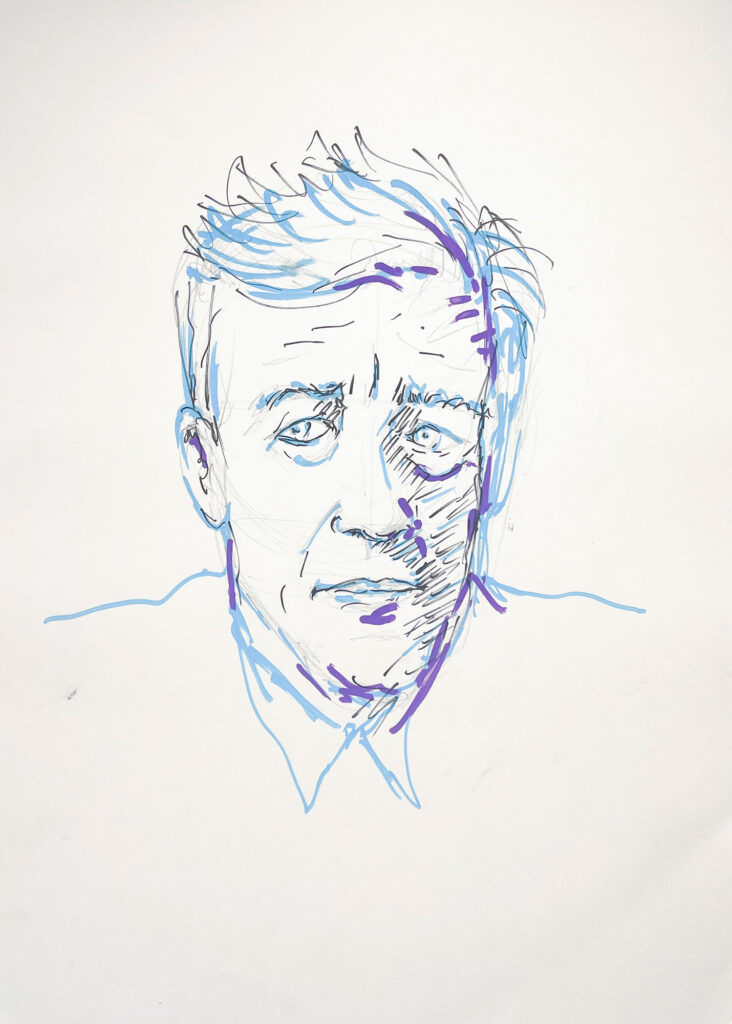

Being heavily influenced by Surrealism, of which Spanish painters Salvador Dali and Joan Miro were key figures, the artist’s visual renderings of the subjects traverse the territories of the transient, ephemeral, spectral, and angelic. A uniquely different kind of visual qualia or style can be detected in this kind of work from the artist’s usual repertoire of figurative and abstract painting. It should be humbly assessed that Bofill’s most successful and consistent body of work to date is the “Double Portrait” not because of its ambitious and large scale but because of its narrowed down scope, clarity of purpose and originality of vision, and its historical and cultural significance in dealing with iconic figures.

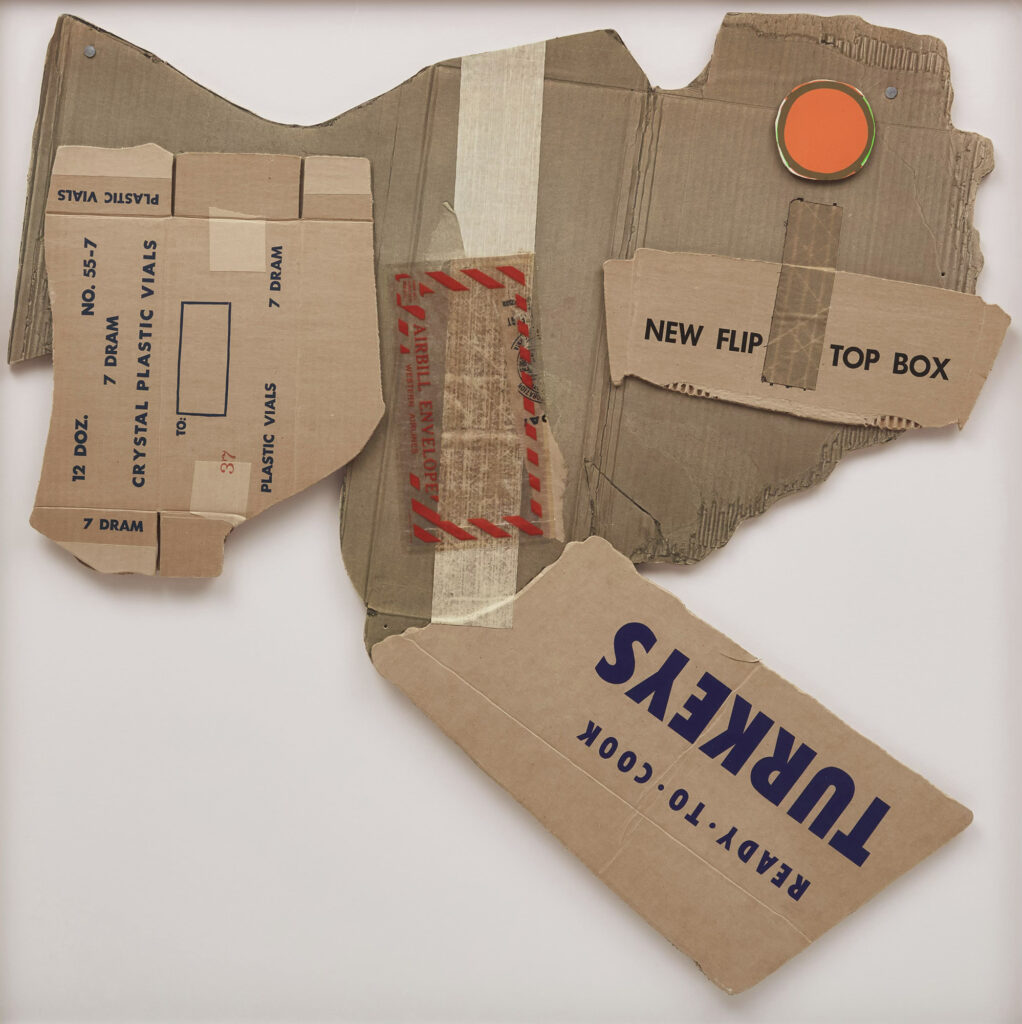

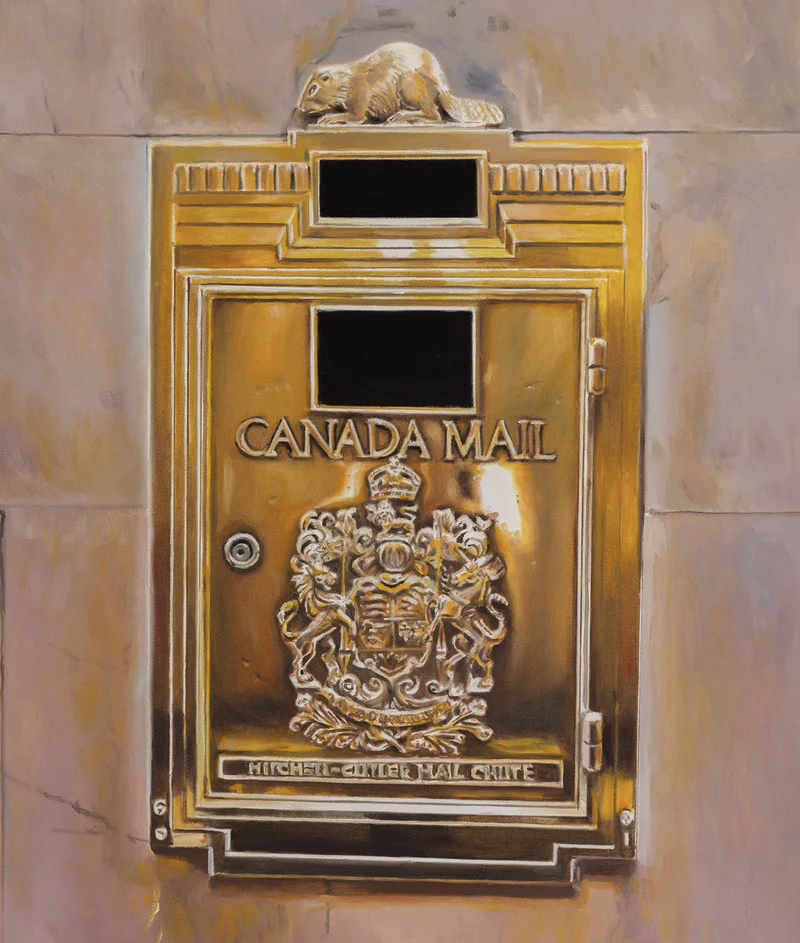

The paper on which the “Double Portrait” is executed takes on a special meaning or significance because the artist often rips out a page from an old art history book or monograph without the image or the slide of the artwork, which the artist purposefully removes, leaving a blank white space for the drawing and painting. This act is akin to the making of a palimpsest, in which the artist recognizes the historical significance of the continuity of tradition, lineage, and canon over long centuries and millennia. The artist appears to suggest, in engaging with figures from the Spanish-speaking domains, the American mainstream, and African and Caribbean origins, that the “Western” history and culture has evolved into a global union of people and ideas and not strictly limited to the history and the cultures of people with a European ancestry. What remains is no longer purely Western people and society but a globalized cultural network of institutions, ideas, trade, and encounters.

A clear distinction can be observed between Bofill and the other “artists” in the streets chasing after famous people: Bofill approaches the “Double Portrait” project with sincerity and lucidity, with the goal of earning the trust of the other by maintaining his own artistic integrity and sensitivity. There is no wax or fluff in Bofill’s work; it is neither over nor underworked; it is made just about right, which is very difficult to achieve for many artists who may overshoot or undershoot from the most ideal outcome. The accidents are no longer accidents but serve as the patterns of an organic and creative process based on discovery and an earnest investigation (for the truth of what they may discuss). While Bofill may not be Picasso just yet, he is a young master in his own rights.

Through repetition of the “Double Portrait,” Bofill slowly accumulates the structure and the voice of his unique style, which is ghostly or angelic at times, traversing into the spiritual and the metaphysical territories, perhaps because the artist is acutely aware of the passage of time and our own mortality.

Why “Double Portrait”? What is the effect of assigning a QR code to each drawing or painting, which leads to a video interview of the person depicted in the artwork?

The answers may be obvious, but the truth requires a great deal of thought and effort to be properly excavated. The video interview may capture in real time the various facial expressions, the speech patterns, the voice, and gestures and the manners of the person. The video may be the shadow of the object, which is the drawn portrait, or it may be the object itself, with the shadow being the drawn portrait. Sometimes, the video may contain more information than the drawing or painting itself.

But art is the process or the act of curation of information. In photography, it is the cropping of the subject, filtering out the unnecessary details or noise. Similarly, the video component of the “Double Portrait” serves to provide context for the framed information and to create an ecosystem of ideas and meaning, of which only a small amount makes it into the visual rendering like the tip of the iceberg.

But, really, art should transcend this kind of curation and accumulation of information, going beyond to capture something invisible and essential, which can never be found in the recorded video of the interview.

And this is where the true test for the artist lies. Even when the artist could not communicate properly with the subject, due to the limitations or differences of language, the artist connected with the subject. And this shows in the paintings. The artist allows the subject to subconsciously alter the internal state of the artist’s own being, which makes Double Portrait in essence an interactive and collaborative project.

“Double Portrait” is not just the words or the act of sitting down and conversing with one another, but it is the intermingling of personalities, the interaction of personal energies, and the interconnection and trust between the two – the observer and the subject. The subject opens up to the observer (who is the artist) because the observer opens up to the subject with great sincerity; the observer/artist also allows the subject to enter into the observer/artist’s psyche, just as the observer/artist is doing the same to read into the subject’s own feelings, lived experiences, and ideological stance. And what results is that the artist’s hand serves as the subject’s hand, on a psychological or subconscious level, which is consistent with the Surrealist and even Dadaist (which evolved from the Surrealist) practice and philosophy. In effect, the observer is observed, and the observed, observing.

Bofill’s portrait of David Lynch is filled with sparks of light (which metaphorically becomes the spark of ideas) that penetrate into the shadows of his face. His strong and determined depiction of Angel Orensanz keeps his identity and ideological persona as a revolutionary and advocate for the advancement of art and culture.

In conclusion, the artist achieves something greater than the sum of its parts for the “Double Portrait” project, by the very nature of its limited focus and artistic philosophy and sensitivity that reflects highly of the artist’s own fine-tuned and intellectual nature. Bofill approaches the subject not as an object of portraiture but as a subjecthood for empathy and human connection, and this is what makes the people respond to and engage so brilliantly and meaningfully with the project.