D. Dominick Lombardi

Over the past twelve years, artist Eleen Lin has looked to Herman Melville’s classic novel Moby Dick for inspiration, in the production of her long running series collectively titled Mythopoeia. With great and expanding depth and detail, Lin takes every angle, including “the idiosyncratic mistranslations between English and Mandarin versions of the book,” up to today’s lesser looked at undercurrents of homoeroticism and multiculturalism to guide her layered narratives. As a result, this stunningly beautiful and curiously complex solo exhibition stands as a must see show for art lovers and artists alike.

In Shining Seas, Lin reveals in exquisite style and varied technical transitions of color and clarity a mystical world in a slightly upturned space that slowly builds in detail and thickness of paint. Here, viewers are left with an expanding experience with surprising clarity that at times crackles and glows in works like The young philosopher (2015), where the ship’s decorative railing, or what is left of the bulwark from the Pequod, appears to protect a nest of eggs perched atop a dangerously damaged deck. Then there are the secondary and tertiary objects like the Chinese yo-yo that hangs from the main mast, the clothespins and the plastic bag attached to one of the cross ropes, the classic red and white life preserver in the distant seas and the large looming ‘shape of water’ woman that bounds up on the horizon. All these components point to both a playful and purposeful approach, adding personal history and global environmental concerns that seep into our subconscious.

Born in Taiwan, raised in Thailand and now living and working in New York City, Lin carries with her three distinct aesthetic influences that produce surprisingly clean color, a flair for the striking narrative and a pliable use of the metaphor. The central moral of the story that has inspired Lin all these years is the dangers of unrelenting thoughts of revenge. In the novel, all the characters die except the novel’s narrator Ishmael, who survives by using his good friend Queequeg’s coffin as a flotation device. In this presentation of the series, the sense of the fruitlessness of revenge moves from the central theme allowing the artist more range to explore the novel’s after effects on her personal past and present.

As the Mythopoeia series has evolved and expanded over the past dozen or so years, Lin continues to push the narrative both inwardly and outward resulting in visual spaces that pull you into the action, tweaking the viewer’s awareness of the natural trajectory of life. A sensation especially felt in the two larger works The young philosopher (2015) and Life folded Death; Death trellised Life (2024), and the medium sized Crow’s nest (2015).

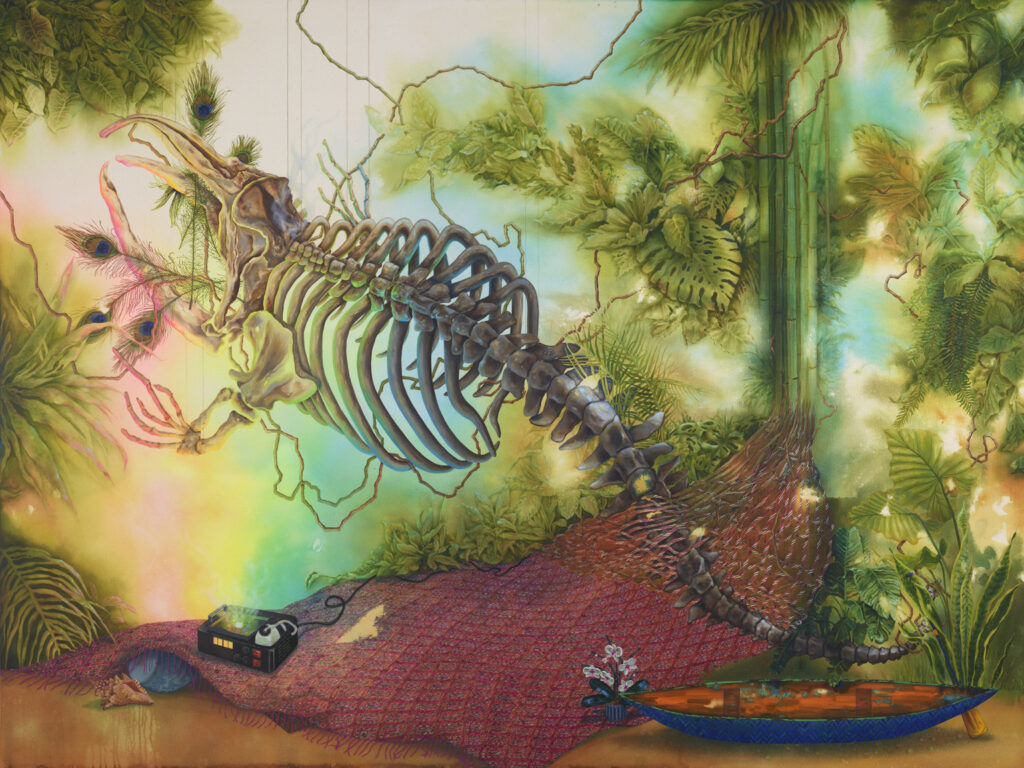

Of the three works mentioned so far, Life folded Death; Death trellised Life is the one that takes place on what looks like a stage set made to look as if it is completely under water. Technically speaking, this painting clearly shows the artist’s process working first with thinned layers of acrylic paint applied to a stretched, unprimed cotton canvas, which in this instance sets up a prismatic background that dazzles the eye. A second layer of thin paint is applied with edgy details revealing large leaf flora and shoots of bamboo rendered just enough not to take attention away from the main subject in center stage, the great sperm whale’s complete skeleton. From there, it looks like Lin switches to oils, painting in the precisely rendered whale remains emerging from the confines of a large net, with its head adorned with peacock feathers. Animated as a puppet hanging from several thin black strings, the whale performs on a stage that has curious details, including a computerized light source that periodically changes color.

Meet. Greet. Fleet. (2018), one of the first paintings you will encounter when entering the exhibit, is one that addresses the homoerotic aspect Lin finds in Moby Dick. Here we see two fishermen meeting in the open sea, in multi-colored boats set against a colorful rainbowed sky. Like the preliminary painting method previously mentioned, Lin begins with a stunning wash of bright colors across an unprimed canvas. Over this, the artist adds a swirling sea populated by a feisty swordfish who pierces the checkered side of one vessel as it fights for its freedom. Since the many-colored rope that winds around the fish to its imperiled state spools out from a box in the boat on the left, and the fact that the attached fish is nosed nicely into the adjacent boat on the right links the two men together in an extended virtual embrace. An embrace that portends to end in a more personal encounter as signified by the unseen sperm whale that spouts water up and into the point where the two men touch.

What I find most telling in Meet. Greet. Fleet. (2018) is the thickly textured clouds in the sky. Using plaster or perhaps modeling paste in the acrylic paint, Lin attaches weighty clouds that seem to suggest trouble ahead, even though both Thailand and Taiwan had or were debating protections for same sex couples at the time of this painting. Then there are the intricately painted hats and shadows that obscure the men’s faces. Perhaps it is a prophetic reference to the middle of the Trump era as we see so clearly today, how certain politicians and supreme court judges are trying hard to turn back the sands of time.

The exhibition Eleen Lin: Shining Seas features paintings, drawings and watercolor, gouache and graphite on paper by Eleen Lin, and runs through July 19 at C24 Gallery in Chelsea, New York City.