by Siba Kumar Das

Madhvi Parekh’s art embodies an intuition of significance that is wholly relevant to a world in the grip of a global ecological crisis. She is an artist for our times.

Susanne Langer, whose path-breaking work on aesthetics is again enjoying currency, thought that in a successful work of art “symbolic form, symbolic function, and symbolized import are all telescoped into one experience, a perception of beauty and an intuition of significance. “Look at Parekh’s paintings. You will see, possibly in a flash, that they exemplify Langer’s great insight.

Madhvi Parekh was born and grew up in Sanjaya, a village in the Indian state of Gujarat. Her father was simultaneously headmaster and a teacher at the local school and, in parallel, the village postmaster and apothecary. A devotee of Mahatma Gandhi, he spoke about the great Indian leader’s ideas and actions to fellow villagers and members of his family. As Parekh told me when I met her in New York in September 2019, she was deeply affected by the Gandhian thought her father passed on to her.

The colors and images Parekh saw as a child have stayed with her all her life. Art critic Kishore Singh, curator of the Parekh retrospective currently on show (September 12-December 6, 2019) at the New York space of DAG, a major Indian art gallery, says, “She was a dreamer and an observer.” The rich imagination that grew inside her melded with a sensibility that became at once artistic and ecological. Singh once asked her to close her eyes and tell him what color she saw. “I see green,” Parekh said, “It’s part of nature. Have you noticed how beautiful a tree looks in a village?”

Gandhi was an environmentalist before the term was invented. Because of his legacy and other factors, a modern environmental movement started in India well before similar movements elsewhere in Asia. Historian Prasenjit Duara thinks that outside the West the Indian movement may be the most diverse and robust in the world. Today’s Indians are environmental sinners just like people elsewhere, but counteracting forces are strong and are buttressed by multi-millennia old philosophical and spiritual thinking. Parekh is not an environmental activist, but she is a Gandhian.

Psychoanalyst and writer Sudhir Kakar sees in Parekh’s art a “magical humanism.” When you see a Parekh painting you grasp its presence instantly. It gives you transcendence, an experience of beauty that takes you beyond yourself. It also gives you an intimation of the interconnectedness of all things, inclusive of humanity, an insight that found a home in India’s ancient philosophy. It’s part of her Gandhian heritage.

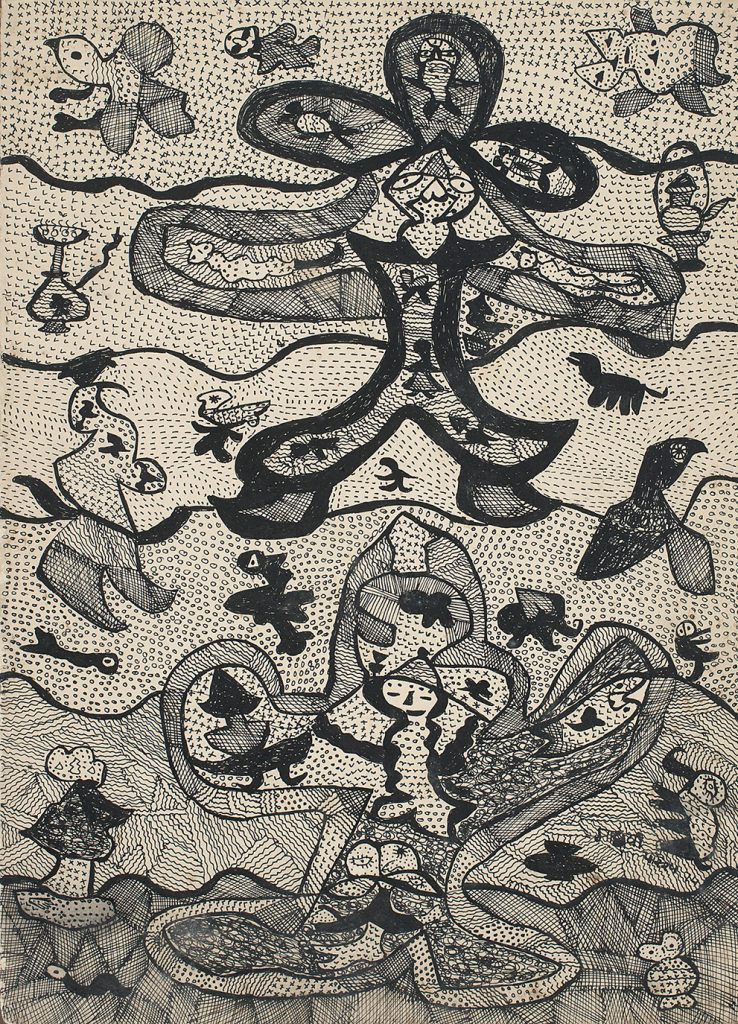

Look at two early works of Parekh’s, both sketches: Running Figure(1972) and Flying Figure (1974). A DAG wall-note highlights the “innate synergy” that connects the myriad elements of each. Wholly apt is this reference to innate synergy. The hybrid figures populating both pictures are whimsically delightful; they also tell you that a form of self-organization may be at play in the world of the biosphere.

Parekh is not an academically trained artist, unlike her husband, Manu, whom she married very young and who took an art degree from India’s famed Sir J.J. School of Art. He was her art mentor during the early years of their marriage – in which task he used Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook. You see the Swiss artist’s influence in these two sketches even as you see Parekh striking out on her own. You see her responding spontaneously to Klee’s dictum: “For the artist communication with nature remains the most essential condition. The artist is human; himself nature; part of nature within natural space.”

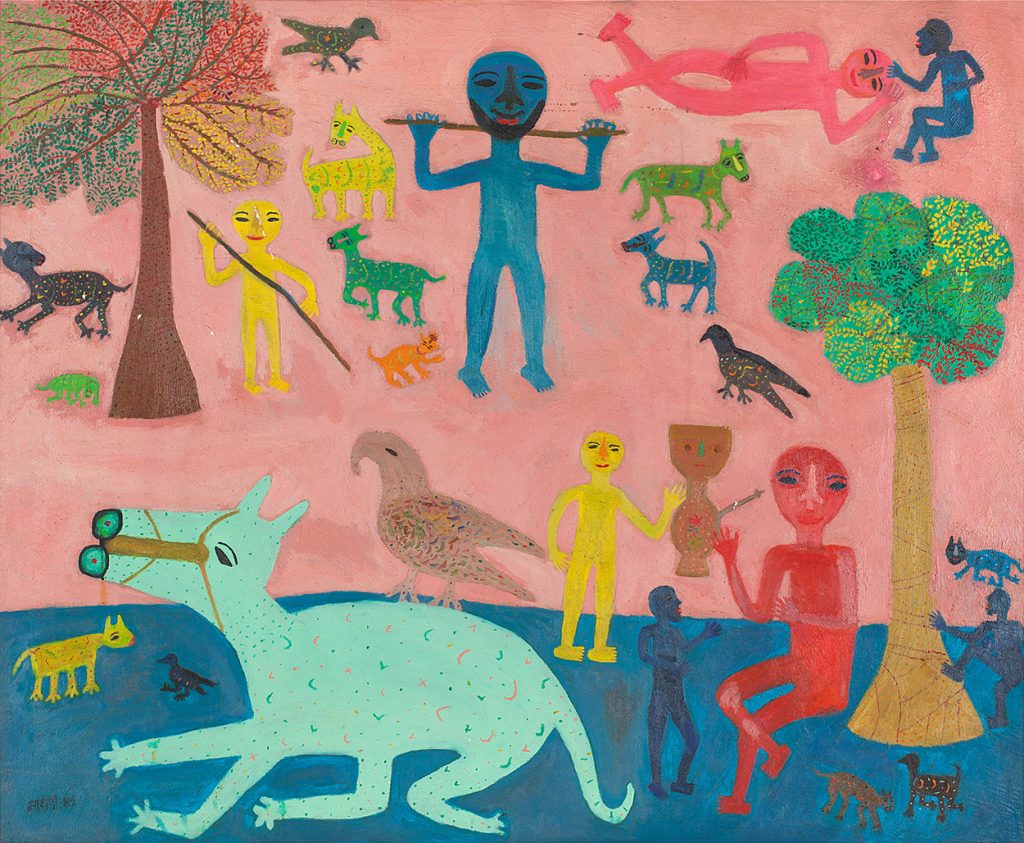

Imbued with a mysticism linked to the nineteenth century German Romanticists, who were influenced by classical Indian philosophy, Klee was attracted to children’s art and so-called Primitive Art. So was Joan Miro, whose approach to shape and form also influenced Parekh. You see Klee’s influence and Miro’s in Playing With Animals,a 1989 oil-on-canvas painting. In this, Parekh is recalling childhood images from Sanjaya. And, as the retrospective’s wall note says, “animals and humans freely commingle, echoing each other in color and line.” The color commingling makes you think of Matisse saying that a goal of his was to make colors sing together. You also recall the colors of Indian ragamalaart, miniature paintings that incarnate visually the modes of Indian music known as ragas. Like Klee, Miro thought that an artist should remain “close to nature.” He said, “Each grain of dust possesses a marvelous soul. But to understand this it is necessary to rediscover the religious and magic sense of things…” Once you’ve seen Parekh’s marvelous painting, you understand Miro’s point straight away.

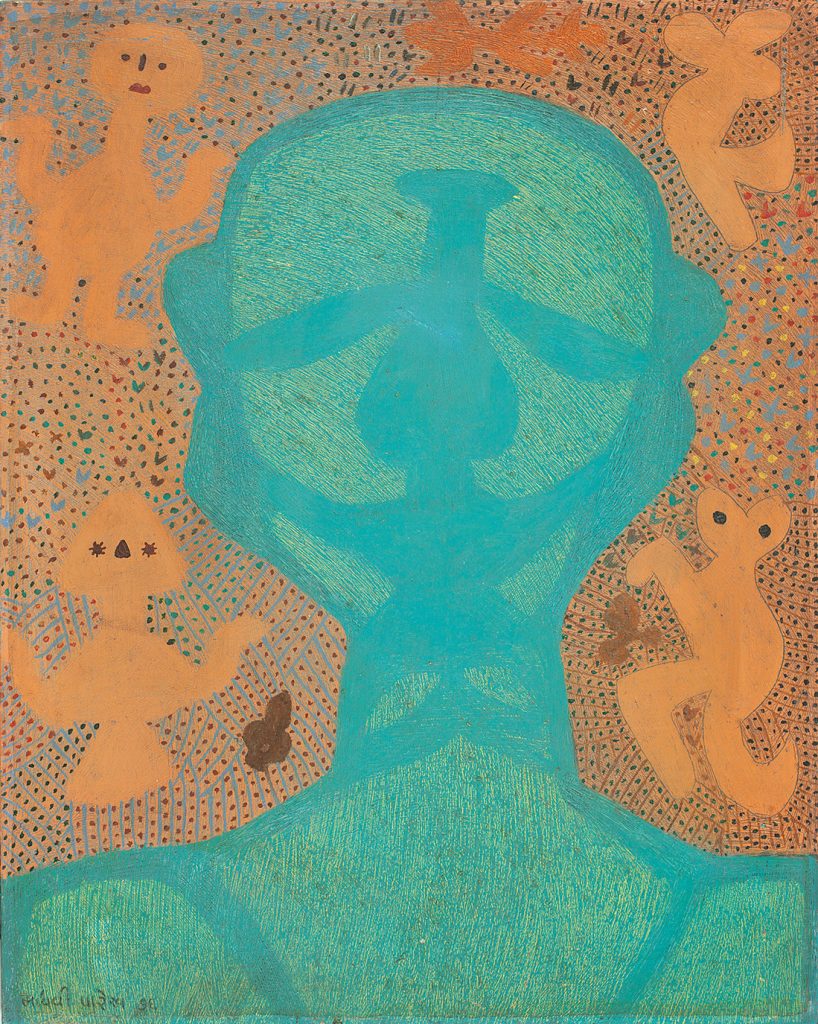

If you keep looking at Playing With Animals and look also at other paintings of Parekh’s, such as Sea God (1971) and Fantasy (Under Sea) (1979), you will understand how insightful art critic Gayatri Sinha is when, in a catalogue essay, she sees as “cognate creatures” the human, animal, and hybrid life forms (tree snakes, snake flowers, etc.) that populate Parekh’s ecosphere. These cognate creatures live in a “flattened perspective” that Sinha highlights – a setting in which they enjoy equality and kinship, gods included, in accordance with the previously noted Indian thinking.

The imagery Parekh carries with her through her childhood memories include not only forms derived from the natural world but also the folk stories and village legends that were a part of her day-to-day life. They include, too, the traditional folk art – such as the floor decorations called rangoli – that enliven the religious rituals and the myriad festivals that punctuate the Indian calendar. She also draws inspiration from traditional Indian textiles, such as the hand printed or block printed Kalamkari cottons. Equally inspirational for her: Pichwai paintings made on cloth or paper, devotional pictures that tell stories about the god Krishna.

Critical commentary on Parekh’s oeuvre often asks questions such as these: Is she a folk artist? Or is she a modernist painter? Such binary thinking does a disservice to Parekh’s achievement. Embedded in India’s folk art traditions as well as in classical Indian painting and sculpture is a deep culture that has endured over millennia even as it has absorbed and metamorphosed ideas injected by successive waves of external influence. Parekh has synthesized the diverse influences she has taken from both inside and outside India, drawing upon this profound wellspring. Emerging from this is a distinctive modernist idiom. Kishore Singh says she belongs to India’s modernist pantheon, and he’s surely right, it being understood her roots lie in the country’s deep culture.

When I met Parekh in September 2019, I asked her about her artistic connection to Francesco Clemente, the Italian modernist who has engaged with India over four decades. She drew my attention to the long, attenuated figures that began to dominate her art in the 1990s, particularly in her depiction of Hindu goddesses. Looking at them makes you think of long, fluid sea creatures, the sea being the earthly kingdom where life most likely began.

Clemente interacted with India’s craft traditions in a highly original way, giving inspiration to art critic Girish Shahane speaking insightfully of India’s deep culture in an essay about the Italian artist. Indeed, it is Shahane who set me thinking about this enduring reality. Each painting of Parekh’s is an independent, freestanding thing: a world unto itself. Yet, instantly, magically, it immerses you in the waters of a deep river.

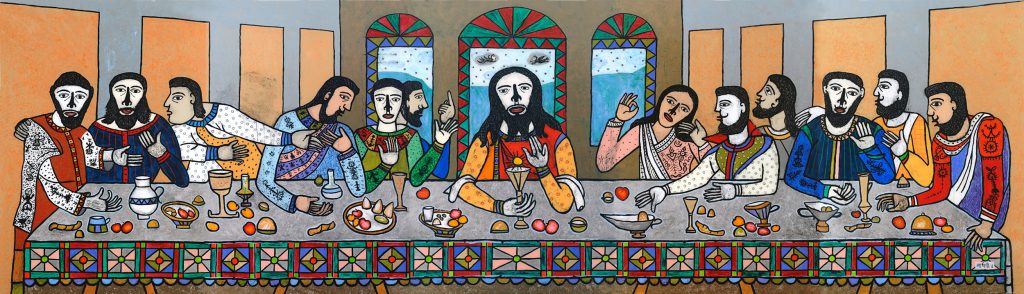

Writing in a catalogue essay about Parekh’s monumental painting The LastSupper (2011), an interpretation of Leonardo da Vinci’s monumental masterpiece, art historian Annapurna Garimella discusses the strategies Parekh uses “to foster identification and empathy” between the viewer and Christ and his disciples. These include depicting Christ holding his left hand in the abhayamudragesture, which represents protection, peace, and the dispelling of fear. Garimella also draws attention to the figures in Parekh’s painting being linked to her earlier efforts to create “animal-like human bodies.” India’s deep culture is at work in the painting, refracted through the prism of Parekh’s great imagination.

In his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, novelist Amitav Ghosh makes this striking remark: “The climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination.” Ghosh calls upon the novel to transform itself as a genre, the better to negotiate the challenging terrain that this crisis represents. Surely, visual art must also rise to the challenge. Environmental art is a growing sub-genre, but much of the art being produced tends to be instrumental. It does not quite live up to the great insight of Susanne Langer’s that I referenced at the start of this article. Madhvi Parekh’s art, on the other hand, gives us visual delight even as it symbolizes our kinship with all other beings in the world. In a time of global crisis, she shows us that art can be a positive ecological force.