The Artwork that Led to the Publication of a Magazine

by Steve Rockwell

I had dropped out of the art scene already in 1972. When I came up with the idea for Pick a Number Between 1 and 99 in 1987, my contact with people I had known from art school and the early studio days had all but ceased. To quote Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone, professionally I was essentially “…a complete unknown.” Distanced from my past efforts, my future presented a blank slate. The situation was at once liberating, yet tinged by a sense of urgency.

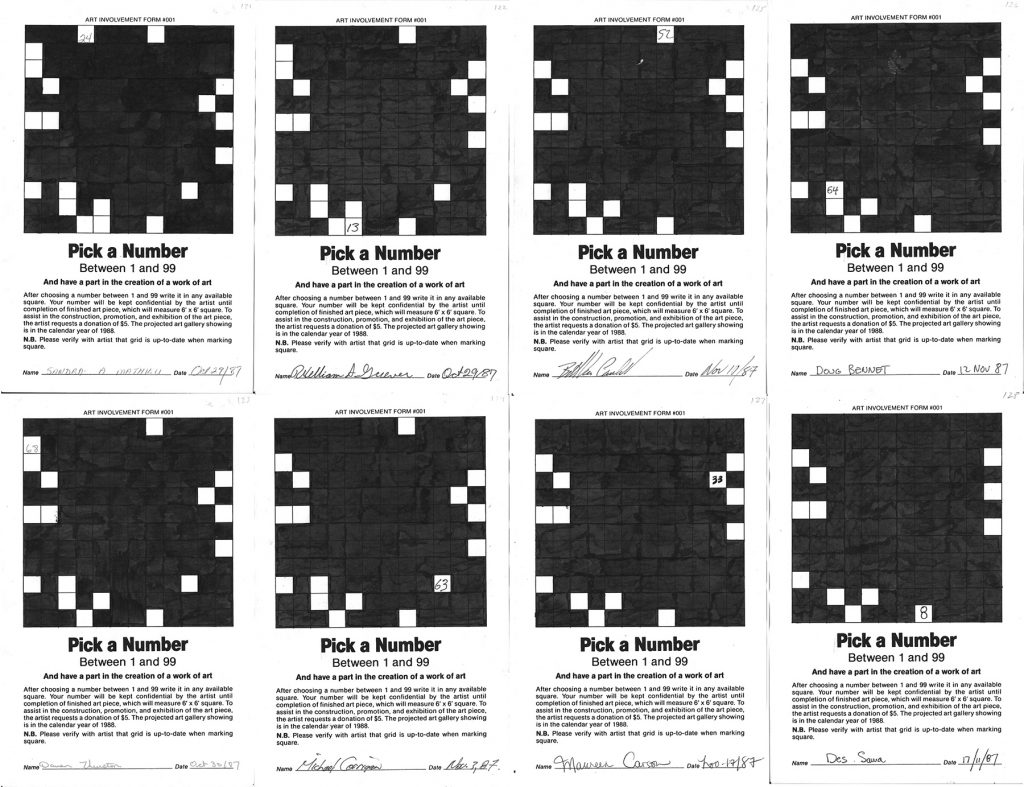

Work on Pick a Number was designed to progress incrementally in the expanse of a public arena, not the hermetic, catacomb strictures of a studio. From this point, my normal working space would be consigned to the finishing aspect of the art – its fabrication. The approach felt fresh and invigorating in a way that I imagined, the impressionists may have experienced working en plein air. Essential to the project was an intent to make the endeavor as idiot proof as possible, allaying the burden of having to plumb any arcane pretensions that the participant may have associated with conceptual art. It really came down to just picking a number and selecting a square. With profundity and import deferred, I soldiered on, adopting the habit of toting my half-letter-sized paper forms as I went, a bit like a photographer with his camera, I suppose – at the ready to frame and capture my subject anywhere, any time.

In point of practice, the project unfolded in a predictably routine way: supported by friends, family, and work colleagues – the low-hanging fruit. Even then, I found myself in an awkward role as somewhat of a huckster in having to sell people on the idea. I needed a cover if I hoped to carry this thing off. In my mind, the right persona might be just the ticket. Steve Rockwell was born April 12, 1987, just two days after Bea Egolf, a typesetter at the company for which I worked, scribed the number 32 into the first Pick a Number grid.

Good or bad at this point, the initiative had at least brought me into a fresh consideration of my creative approach. How far can I stretch this artist character? How will it affect my working method as I progress? Admittedly, all this had been a wry jab at the solemnity and, in my view, needless complexity of Sol Lewitt’s approach to conceptualism. His Wall Drawing #232: The location of a square had been the singular springboard for this new direction. The 19-line geyser of a sentence in Lewitt’s set of instructions, however, gave me a headache. I would rather have assembled an IKEA bookcase. “A square, each side of which is equal to a tenth of the total length of three lines, the first of which is drawn from a point halfway between the center of the wall and a point halfway between the wall and the upper left corner and the midpoint…” and so on. Nevertheless, I did like its precision and aura of certainty – its final executive clarity.

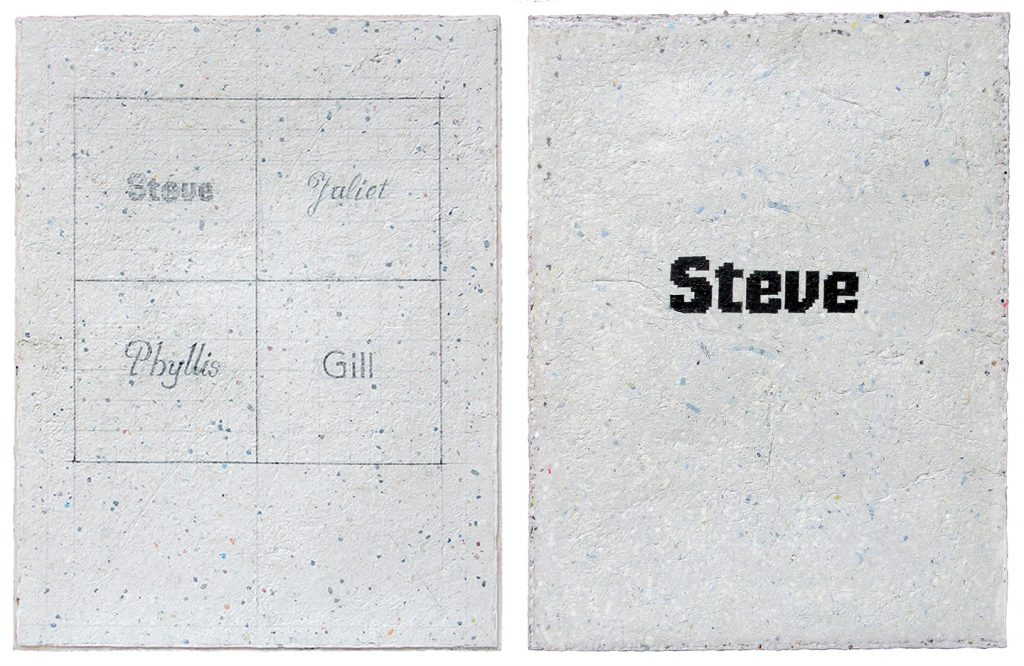

Looking back now, I see that the complexity that I had dispensed with in Lewitt’s instructions, had merely been displaced by the Steve Rockwell character, as played out in the 139 separate negotiations with the participating individuals over the eight month period required to complete my Art Involvement Form #001 project. An important distinction lay also in the final product. While Lewitt employed fabricators and assistants to complete his work, following detailed instructions to a specific end, the final product in the Art Involvement pieces were provisional and generally arbitrary. Decisions about the look of these pieces could be made once the information had been collected. There were two key aspects to my approach – data generation and data implementation, necessarily facilitated by a social network. It wasn’t lost on me that their conception occurred in tandem with the 80s development and proliferation of the personal computer. It’s worth considering the role that Steve Jobs played in hyping the warm, human aspects of computing, made conspicuous with the 1983 release of the Apple Lisa, named for his daughter.

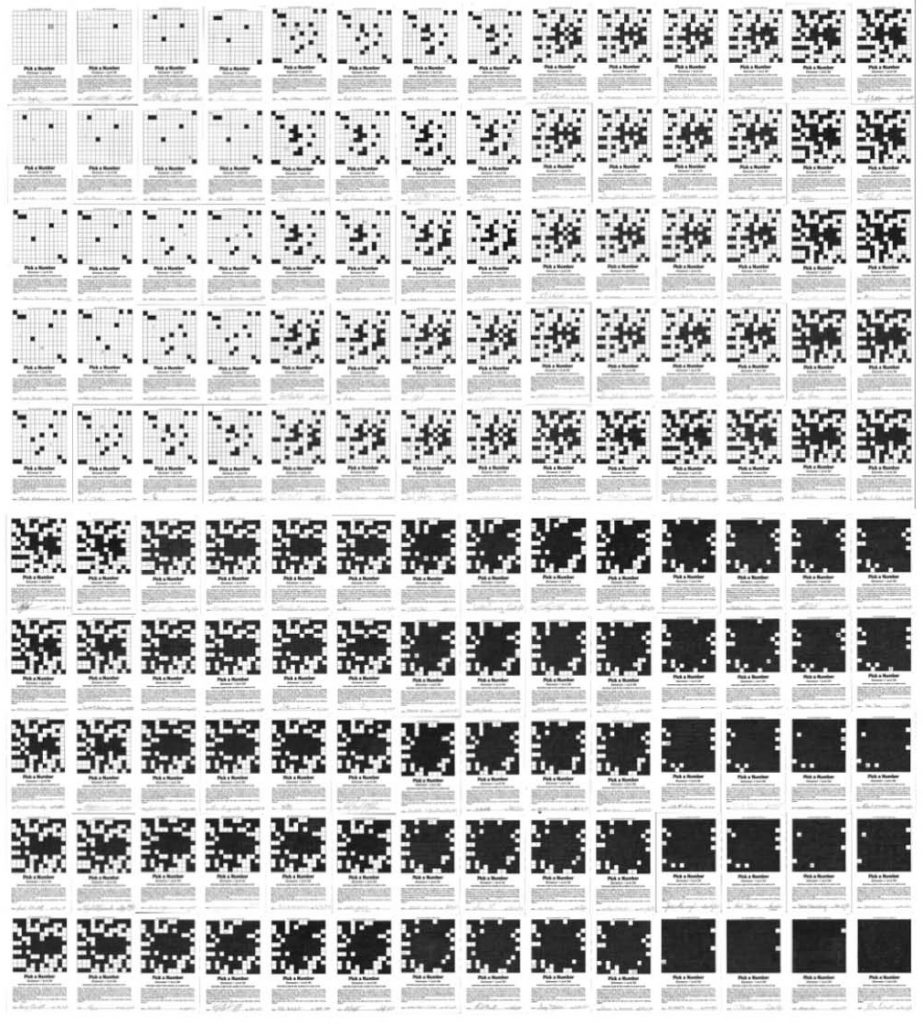

Despite my best efforts to manage the progress of the Pick a Number piece, a fly dropped into the ointment with author Jerzy Kosinski’s contribution. After a lecture he had given in Toronto, he either didn’t catch, or simply ignored my instruction to mark a single number into the space of his choice. Instead, he gobbled up all of six squares, scribbling in three combinations of sixes and nines with an obvious eagerness. At the time, I thought that the blunder had spoiled the intended symmetry of the piece. Participants in the 12 by 12 grid project ought to have generated a tidy 144 completed forms. When displayed at their exhibition, the wall installation of Pick a Number sheets were arranged into 24 rows six deep as planned, but with five unintended blanks spaces remaining at the end. Kosinski had inadvertently blocked five people from taking part in the project and given the piece something of an unfinished look. In retrospect, the “mistake” may have turned out to be fortuitous. It had bothered me somewhat that the white square on the last participant’s form would remain without the blackening. In the preparation of this article, and seeking a way to best configure the 139 sheets of paper, a possible solution presented itself. Why not ink in that last counter and punctuate the form by my own signature? This would make it an even 140 and allow for its display as a grid arranged five forms deep with 28 rows across.

Not surprisingly, given its social aspect, the Pick a Number project had quickly edged towards a narrative, the generation of ciphers progressively threading disparate individuals into a kind of information tapestry, even more so with the passage of time. The first tragic instance of it, as I recall, was the sudden passing of a work associate, Leo, who had once played Olympic hockey for Italy. Hearing the news affected me in a strange way. His contributing datum had made him inadvertently part of a larger story, the transcription to which I had served as a witness. Leo’s number pick had been a peg driven into the tent of a specific moment in time and place.

To be expected, life passages are the Pick a Number events that etch the deepest into relief. Represented on the form as a fade from white to black, they analogize the nakedly sharp edge of our existence. From the beginning on April 10th, 1987 to its completion on December 2nd of that year, various personal stories constitute an ever-expanding tableau vivant, the forms serving as delineating markers, a canvas upon which a mélange of dramas continue to play out into the present. All along, it had been the personal part of the information gathering that had made the simple act of selecting numbers into something of a life moment – and as long as narratives are being tracked, Pick a Number seems never to close out.

I have come to appreciate the project as a private diary – people clustered into specific times and places, a sequential log of family, friends, and people that I knew, worked with, and met casually in 1987. Two Toronto mayors became part of Pick A Number. I bumped into Art Eggleton, the longest serving Mayor of Toronto, striding past Henry Moore’s Archer and across Nathan Phillips Square, the mayor presumably fresh from a council meeting at the adjacent City Hall. After a brief verbal joust, he relented and signed the form. Then mayor of North York, Mel Lastman signed my form without hesitation at a public function. He would preside over an amalgamated Toronto from 1998 to 2003.

I can see from the dates on the forms #11-20 that Thursday evening on April 16 would have involved a drive with the family to parents in Northern Ontario for Easter. The next day on Good Friday seven family members signed forms at our stay at my parents. Three more were numbered on Easter Sunday, indicating that we had paid a visit to the in-laws.

All of 22 forms were inscribed on a single day, August 30th at Toronto’s Canadian National Exhibition. The North York Arts Council had provided some booth space for artists, giving my outing there a carnivalesque step-right-up-folks flavor. While at the exhibition, I took in a set by rockabilly legend Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins, who obliged me with a 69 on his Pick a Number form. The three members of another CNE act, the Aussie band, Mind The Gap, also picked numbers. A quick Google search just revealed that their head-banging anthems and reflective ballads are still reverberating. Before his success in Canada, lead singer, Patrick McMahon, had arrived at the Vancouver Airport in 1986 with a suitcase and a guitar, not knowing a soul. My recollection is that McMahon had picked the name for his group from the caution signs that he observed riding on the Toronto subway.

My local in 1987 was the Ben Wicks – a lode rich in Pick a Number participants, which included a former Playboy bunny who had apparently once worked at Hef’s Chicago club, and Maury Mason, a Greenpeace spokesman who now manages the Vipassana Meditation Center in British Columbia. It was Mason who had reported on the six Greenpeace members who were chained to the British vessel The Gem in the protest of the dumping of 5,000 barrels of radioactive waste into the Atlantic.

Pick a Number was the first of several art involvement projects that would sprout from the original seed idea, the second being Decade, which had its showing as part of a group exhibit in December 1988. This work involved putting up for sale days of a purchasor’s choice of the ten years leading up to the year 2000. Although begun and created in December 1987, Color Match Game would not be exhibited until 2004, undergoing refinements and developments that continue into the present. In that respect, the work shares a characteristic common to all of these pieces. Since the final visual appearance of each is provisional, there is a regenerative aspect to the works that lends unpredictability and frequently a surprise of outcome.

These three columns of type constrained by the pages of dArt magazine owe their direct genesis to the burgeoning line of art involvement projects, the eighth being the sculptural Gallery Space, which led to the book work Meditations on Space in 1996, and finally dArt International magazine in 1998. In the strictest sense the subject, of course, is still space.

Gallery Space was part of the first Steve Rockwell solo exhibition at the Arnold Gottlieb Gallery in January 1989. That summer, Gottlieb featured the Steve Rockwell Sandwich, driving home the idea that the application of a program, or menu retains its freshness in the perpetuity of production. Since then, the sandwich has appeared on restaurant menus and been featured at a 2004 Arts and Eats fair in San Antonio, Texas. The sandwich inspired a new food product, the dArt Burger, made available to order from a Toronto restaurant menu in 2011.

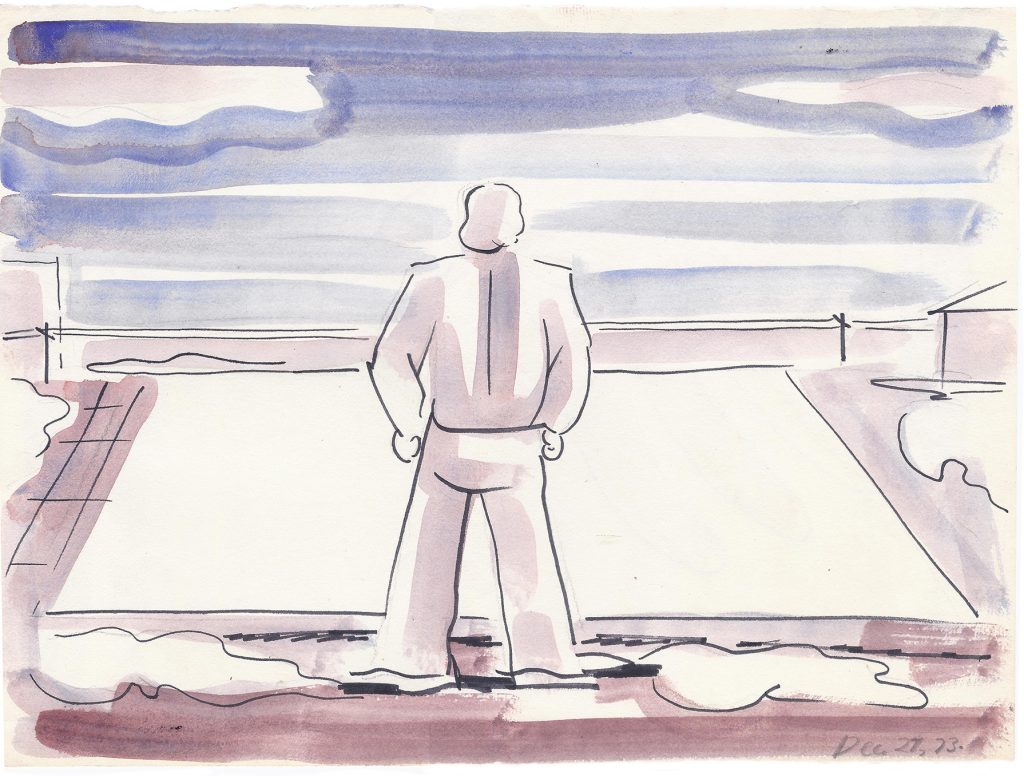

Long before Pick a Number and all that followed, is an ink and water color sketch that I came across by Jouko Salomaa done in 1973 that foreshadows the reflections on space that found expression in the late 80s, created by the individual who would rebrand his art in the persona of Steve Rockwell. Originally an untitled sketch, I decided to name it Field Work in the preparation of this article, as a way to knit together what went before with what came later. At the moment of its rendering, not much context could be inferred, that is until the current reconsideration of Pick a Number, where the arena of my labor would drift from one side of the studio wall to its exterior.

Little did I know when I sat down for the lecture by The Hermit of 69th Street, that strands in the narrative of a writer of “autofiction,” would eventually be woven into the visual art of another fictive persona. Since Kosinski spent a good part of his late career dodging accusations of plagiarism, the questions that arise have validity and currency. How much of what an artist reflects is genuinely his own? Admittedly, by Kosinski’s definition, the writer of autofiction was a teller of neither truth nor lies. I’d like to think that Steve tells truths.