by Siba Kumar Das

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

It’s not often that a new art movement shoots into life just as a nation needs it socio-politically. This is exactly what happened in 1947, the year India threw off the yoke of British imperial rule, when a group of young artists banded together in Mumbai (then Bombay) to launch the Progressive Artists’ Group with a view to creating, in the words of its manifesto, a “new art for a newly free India.”

By organizing from September 15, 2018 through January 20, 2019 a show comprehensively presenting the group’s vision and achievements, the Asia Society Museum in New York is making an indispensable contribution to art history. The group’s many achievements still reverberate today. Seven decades later, the Progressives’ ideas and legacy provide a lodestar for India and a wider world beset by the politics of insularity, division and exclusion – a world in which cultural freedom is under threat.

In the catalog accompanying the Asia Society show, curator Boon Hui Tan, also Museum Director and a Vice-President of the Society, complements the essay contributed by guest curator Zehra Jumabhoy by contextualizing the legacy of the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG) within a wider Asian context. He concludes in his essay, “The battles over the art of postcolonial Asia are essentially battles over the ideological basis and values of the new nation, which are shaped by the changing structures of power over time.” In her essay’s conclusion, Jumabhoy, also Associate Lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, calls for reclaiming the core message of hope embedded in PAG’s “progressive vision” – a message applicable, she believes, to the political landscapes of both India and the United States. In essence, the group’s vision and accomplishments, as articulated by the Asia Society show, have ramifications extending well beyond India’s political and cultural geography.

Back in 2010, art historian Iftikhar Dadi saw in PAG’s artistic adventure an aspiration to go beyond the boundaries of the national to open up “the self and the nation to a wider dialogue with universalist aspirations of equality and freedom.” How right he was, the show tells us. Discussing its timeliness and importance in a recent article, writer Tausif Noor suggests that it has become vital “to re-examine the Progressives’ vision of India as a nation of commingling and complementary differences.” But, taking our cue from Dadi, we might also assert this: the same vision throws light on the sustenance of pluralist democracy and cultural diversity amidst challenges now emerging not only in India but in many regions of the world.

What did the PAG artists mean by declaring themselves progressive? The deployment of the term in the context of culture had already become current in India since the 1930s with the founding of the Progressive Writers’ Association, which, as Dadi reminds us, “had rapidly emerged as a highly influential group of writers producing literature of socialist realism and critique across India in numerous languages.” Francis Newton Souza, the main driver propelling PAG’s creation, was, in his early youth, briefly a member of the Communist Party of India. Yet, within a year of PAG’s birth, in 1948, he wondered why his group still called itself progressive. “We have changed all the chauvinist and leftist fanaticism which we incorporated in our manifesto …Today we paint with absolute freedom for contents and techniques.” Over a decade later, when he was resident in London, having migrated there in 1949, Souza even said, “I don’t believe that a true artist paints for coteries or for the proletariat. I believe with all my soul that he paints solely for himself.” In saying this, Souza spoke for himself, and PAG had in any case disbanded in 1956. The Progressives clearly followed diverse, distinctive agendas that could not be distilled into a single artistic program. Yet, all of them willy-nilly responded to their socio-political milieus even as they expressed themselves, some clearly addressing issues with social implication, and, in the process, they evolved an aesthetic that spoke to the cultural needs of their time even as their personal artistic vocabularies diverged.

Present at PAG’s creation, as founding members, were Souza and five other artists: K.H. Ara, S.K. Bakre, H.A. Gade, M.F. Husain, and S.H. Raza. The six came from diverse social and religious backgrounds and were for the most part quite poor when they began their careers. Over time the group expanded to include six other artists: Akbar Padamsee, Tyeb Mehta, Krishen Khanna, V.S. Gaitonde, Ram Kumar, and Mohan Samant. Unfortunately, the only woman artist associated with the group, Bhanu Rajopadhye, did not maintain the link beyond 1953.i

The Progressives succeeded in their agenda of progressing beyond the artistic paradigm set by the cultural institutions founded during the British Raj, especially the Sir J.J. School of Art, as well as the achievements of twentieth century artistic predecessors – the Bengal School and Amrita Sher-Gill most prominently – by internalizing in a transformative way the insights of Western high modernism. This assimilation, as the Asia Society show brings home to us, became a profoundly imagined Indian construction because PAG artists integrated modernist concepts, especially things pushing outwards formalist possibilities, with ideas they inherited from India’s cultural history, an ancient history spanning many millennia. Two more influences need mentioning. The Progressives borrowed ideas from India’s extremely diverse folk art and culture. What’s more, they took ideas from sister civilizations in Asia, especially the arts of China, a country with which India has interacted for at least three millennia. To the Asia Society show’s curators we owe a big debt of gratitude for an art history contribution of great significance: their spotlighting of a significant intra-Asian connection.

Many factors enabled the Progressives’ achievement of a cross-cultural synthesis. This essay will address this issue in an attempt to extend the ground so well covered in the exhibition catalog. Three integrating factors are especially worth noting.

Iftikhar Dadi has identified one of these by saying that formalism–that is, formalism such as that catalyzed and promoted by modernism – “is itself more amenable to Indo-Persian aesthetics than is academic realism,” the nineteenth century European realism promoted by colonial British policy. Here, Dadi was of course referencing the great tradition of Indian miniature painting that reached its apogee in the sixteenth century through an integration of two traditions that were themselves products of centuries of cultural hybridity – Persian painting, embodying an Islamic aesthetic building upon earlier traditions, and an Indian art that represented the meeting of three streams emanating from the needs of three religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, especially the latter two, given the strong possibility that Indian miniature painting first sprang to life in the eighth century in the eastern part of India, under the umbrella of the Pala dynasty. Emerging from this immense, ancient, swirling backdrop was a natural desire for harmony and emotional balance. Formalist aspects of modernism in art were seen to respond well to this aspiration, especially through abstraction.

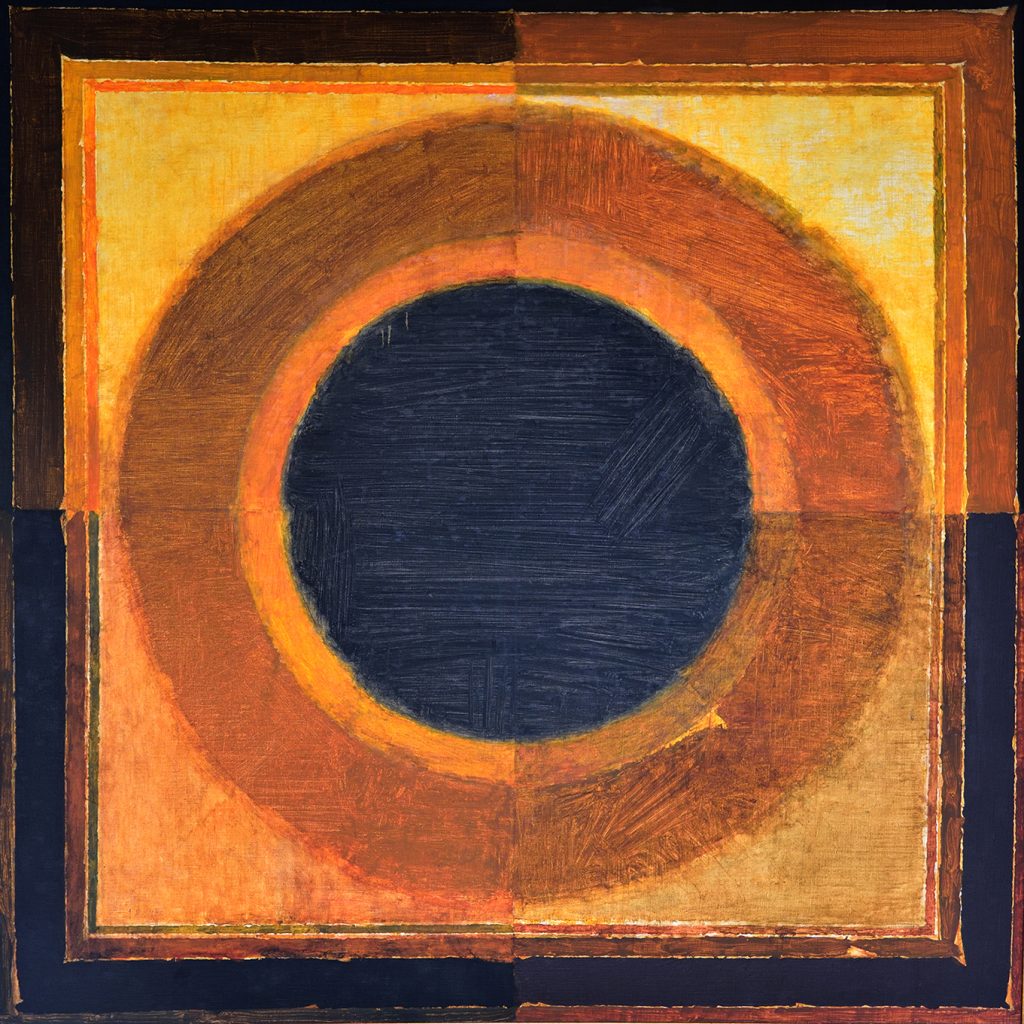

In thinking about this, one might recall the principle that Henri Matisse laid down when he said in his Notes of a Painter (1908) that even as color is used expressively, the content being expressed should be stable and harmonious. Discussing Matisse’s goal in a witty, wonderful book – What is Painting? – Julian Bell suggests that Matisse’s goal, while pursuing his intuitions about color, was “to reach beyond transient emotions: to arrive at a transpersonal, by way of the personal.” Surely, similar goals animated the numinous, transcendent art of both S.H. Raza and V.S. Gaitonde. In his memoir-essay Looking Out of the Looking Glass, published in 2013 as part of a substantial book on PAG published by DAG (Delhi Art Gallery), Krishen Khanna speaks of Raza’s engagement with symbolic metaphysical forms. Of Gaitonde, he says, “His gradual exploring of a colour with all its tonalities is reminiscent of a Vilambit Khayal.” This is the slower of two main stanzas of a North Indian vocal musical form embracing cycles of improvisation that, through melody and rhythm, transport you to a world beyond words.

The Darashaw Collection. Image courtesy of the lender

A second area of congruence arose from Indian miniatures employing color –frequently vibrant, intense stains – in both symbolic and expressive ways. Towards the end of the nineteenth century and early in the twentieth century, the desire to allude to a world beyond the arena of the painting as well as the desire to stimulate feeling in the beholder pushed European artists to shift boundaries. Eventually they crossed the frontier into modernism, brandishing a passport called color. Think of Vincent van Gogh now, and his friend for a while Paul Gauguin, whose colorism was a big influence on Amrita Sher-Gil. The PAG artists rejected her legacy but, in practice, succumbed to the logic that moved her artistic practice. Color’s expressiveness and its ability to create feeling played into their agenda of responding to a new nation’s concerns, which they personally felt to be their own. So, for example, M.F. Hussainii drew upon the colors and images of Basohli miniature painting (and other Indian sources) even as he borrowed ideas from Picasso and other Western artists.

The third integrating factor is this: the PAG artists operated in a cultural milieu that was decisively influenced by thinkers like Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Not only a writer and educator, he emerged late in life as an innovative artist. In 1921, Tagore claimed that the ‘idea of India’ militated “against the intense consciousness of the separateness of one’s own people from others.” Discussing Tagore’s statement in The Argumentative Indian, a collection of essays on Indian history, culture and identity, economist and philosopher Amartya Sen, another Nobel laureate, suggests that it has implications within India and the arena in which India relates to the world. Sen’s suggestion is that, both internally and externally, Tagore’s claim “proposes an inclusionary form for the idea of Indian identity.” Sen admits, “It would be hard to claim that there is some exact, homogeneous concept of Indian identity that emerged during the [country’s] independence movement as a kind of national consensus.” Different leaders and thinkers, such as Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, took diverse approaches on many aspects of the idea of India. But all of them shared “an inclusionary reading of Indian identity that tolerates, protects and indeed celebrates diversity within a pluralist India.” It is this inclusionary idea that brought the Progressives together, in terms of their art and the social legitimation they aspired to in different ways. And along with it, hand in hand, came their openness to a millennia-old Indian cultural syncretism that fertilized their absorption of modernist ideas.

In the early twentieth century, thanks to developments in the West, a paradigm change had taken place in the world of art, and it was only appropriate that Indian artists should engage with the new paradigm. In fact, well before PAG, as art historian Partha Mitter has shown, Indian artists such as Rabindranath Tagore and Jamini Roy found in Western avant-garde thinking ammunition for their anti-colonial resistance. Mitter also reminds us that, in the nineteenth century, Western Romanticism received from Indian philosophical thought a most important infusion, and the resulting synthesis had produced many mutations all the way to the twentieth-century Existentialists as well as Henri Bergson and Wilhelm Worringer. This stream of influence and confluence affected artistic modernism, by contributing to the cultural climate that created and sustained it. It was reflected, for example, in the thinking and practices of Wassily Kandinsky and other modernists in their development of a flat, non-figurative art and their search for an alternative to materialism.

Already by the eleventh century, as art historian John Guy has shown, a Pan-Indian artistic sensibility had developed in the subcontinent. This “shared style and expressive language” was dominated by two aesthetic concerns: “a striving for fidelity to nature” that was balanced by “a desire to generate powerful emotions through pictorial imagery and literary allusion.” Let me now suggest that this Indian aesthetic came into play most vividly and expressively when, in the sixteenth century, Indian art absorbed an earlier infusion of European artistic ideas via contact with the European Renaissance – a topic addressed in a most original way by art historian Kavita Singh. Painters of miniatures at the Mughal court took readily to European ideas regarding naturalism, chiaroscuro, and perspective but did not progress in linear fashion towards a full-fledged adoption of European practices. Rather Mughal painters preferred a hybrid aesthetic wherein these ideas were imaginatively combined with an art that continued to draw upon Persian conventions with regard to symbolism, allusive practices, and composition. Moreover, given the fact that most Mughal court painters were not Persian expatriates but indigenous Indian artists, it seems to me that the Pan-Indian style identified by Guy was still a living force, especially with regard to the importance of symbolic imagery and artful allusiveness.

Let me now go on to suggest that this Pan-Indian style was a vigorous force even in the second half of the twentieth century. Subliminally and perhaps even overtly, it directed the hands of the PAG artists as they sought the ‘new art’ they proclaimed in 1947. It guided them as they selectively took ideas from Western modernism to create a ‘decentered’ modernism in India. It guided them as they propelled the forging of a new synthesis, which also absorbed ideas from other Asian artistic traditions. If you visited the Asia Society show and took it all in one sweep, albeit a slow one permitting deep looking, you would be struck by the salience of a few themes.

The Alkazi Galleries Inc. The Alkazi Collection of Art. Image Richard Goodbody

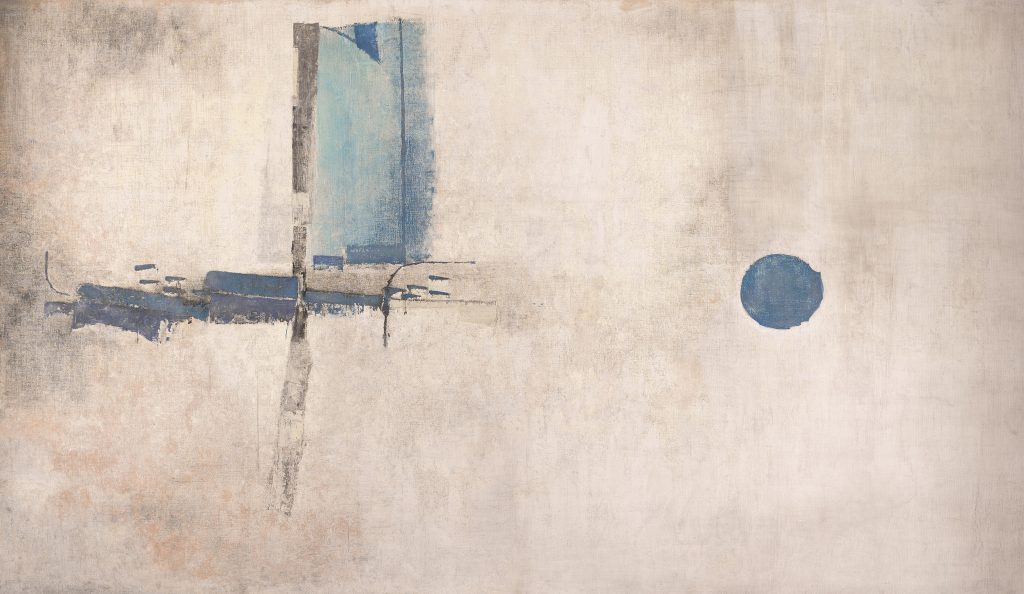

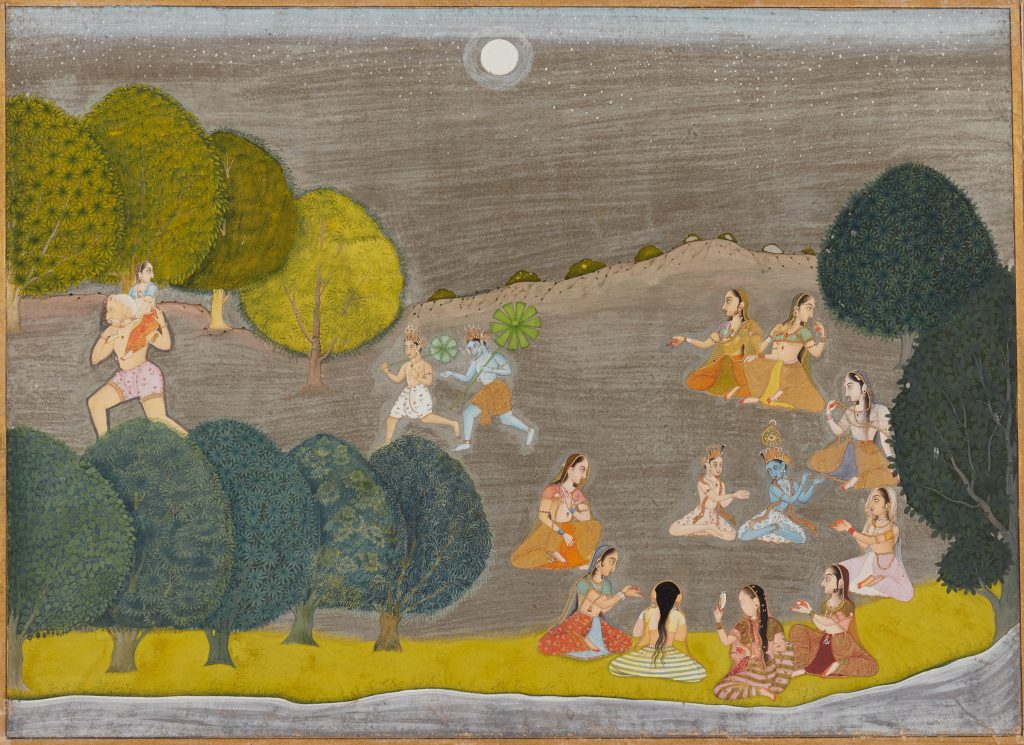

To varying degrees and in different ways, the PAG artists showed that there is but a porous frontier between abstraction and figuration. Applying the previously noted syncretism of Indian culture, the Progressives created different combinations of the two styles. Think of Souza’s symbolism-laden figures embodying an intense experience of alienation and suffering – here was an artist who stretched the possibilities of painting. Think of Husain’s admixture of simplified, Cubism-inflected figuration with an expressiveness arising from his use of color to create feeling and to compose the picture; think too of his employing color in combination with imagery to allude to ideas emerging from Indian art and culture, including the quotidian culture of ordinary Indian people. And now think of the forms of abstraction towards which Gaitonde and Raza and S.K. Bakre gravitated – abstract styles that were also in their own ways highly suggestive and allusive, pointing to Indian and, in Gaitonde’s case, other Asian artistic and philosophical ideas, and even transporting you beyond the picture frame. During your visit to the show, make it a point to look intently at a Rajput miniature painting from ca. 1690 titled Krishna and Balarama in Pursuit of the Demon Shankashura, which the exhibition’s curators have juxtaposed with S.H. Raza’s Bindu (ca.1980s). It’s astonishingly close to a modernist painting. Consider its flatness, its simplification of landscape elements, its employment of color at once to stimulate delight and compose the picture, its juxtaposition of multiple narratives, its suggestiveness and symbolism – modernism is not a stone’s throw away, but it is not far down the road. Yes, Raza’s painting could be seen as a response to the aesthetic embedded in the Rajput miniature. But, applying your imagination adventurously, you could even say that the Progressives’ entire oeuvre, broadly speaking, is just such a response. All in all, a glorious creativity arose when the Pan-Indian aesthetic, incarnated in the sensibilities of the PAG artists, encountered the ideas that these artists took from Western modernism.

Collection of Jamshyd and Pheroza Godrej. Courtesy of the lender

The Progressives succeeded in creating “a new art for a newly free India” by marrying their individual imaginations to their commitment as a group to a pluralistic India, an idea completely in accord with the inclusionary syncretism they inherited as Indians. Their art solidified and enlarged a new edifice – Indian modernism. Some of them pursued career trajectories abroad, carrying forward their creative evolution through the urgency and stimulation that came from their interaction with new influences. Over time international recognition and impact followed for them and the PAG artists who stayed home. The art world has come to accept the reality that modernism had many centers.

Zehra Jumabhoy rightly asks, “Is it not time to give the Progressives’ visualization of a plural India a second chance?” At a time when India is experiencing a high economic growth rate but finding challenges in making that growth inclusive and environmentally sustainable, the pluralist vision embodied in India’s constitution is not simply a desirable, aspirational idea but a critical necessity for generating the innovation and creativity at all levels without which India could not create widespread prosperity for its citizens. And those citizens now comprise a share of world population that will soon reach 18 per cent. Jumabhoy’s question has ramifications for India and the world.

i We know of Bhanu Rajopadhye’s association with PAG because of some smart

sleuthing by Zehra Jumabhoy.

ii Worth noting is M.F. Husain: Restless Traveler, an exhibition mounted by New York

City’s Aicon Gallery from October 26-December 1, 2018 partially paralleling the Asia

Society show. Themed around Husain’s constant travels throughout the world and the

inspiration they had upon his work, the exhibition’s centerpiece is a monumental nearly

sixteen feet long acrylic-on-canvas painting called “Beyond Theoria”.