by D. Dominick Lombardi

With three exhibitions opening at the Hammond Museum, the big surprise is the work of Sam Bartman. Born in Brooklyn, NY in 1922, Bartman has spent the last 60 years of his life creating stirring paintings that combine some of the most the incompatible materials. In experimenting with what he calls his “special sauce”, Bartman has somehow tamed a mix of resins, varnishes, motor oil, glitter and automotive paints with oils and acrylics that results in everything from endlessly crackling surfaces and minute swirling storms of color. There are even the occasional brushstrokes that push the variously drying materials around leaving fossil like impressions of battered brush hairs sorrowfully spent in a furious wake of swished paint.

Bartman is an outsider. His unconventional and periled approach to previously incompatible materials could only have come from a place of pure, unrestrained, fearless experimentation common to this type. He scrapes, he pours, he projects his insights and instincts directly onto strange repurposed square surfaces comprised of millions of tiny glass beads attached to a sour yellow ground. In some instances, it all comes together looking somewhere between the more vigorous works of Vincent van Gogh and the paintings by Max Ernst that feature his decalcomania or grattage technique.

In reference to, or perhaps in his channeling of Van Gogh, you can see in Untitled (2008) and in First Attempt (1998) a similar heaviness and deliberateness in the paint application between the two artists. Comparatively, where Van Gogh is painting highly expressive and intensely colorful works en plein air; Bartman paints at night, indoors, using artificial light and in the solitude of his basement on a commandeered Ping-Pong table. Surrounded by the wafting waves of fumes and off gases his techniques produce, Bartman pulls from his daily observations filtered through a subconscious that allows all and any twist or turn.

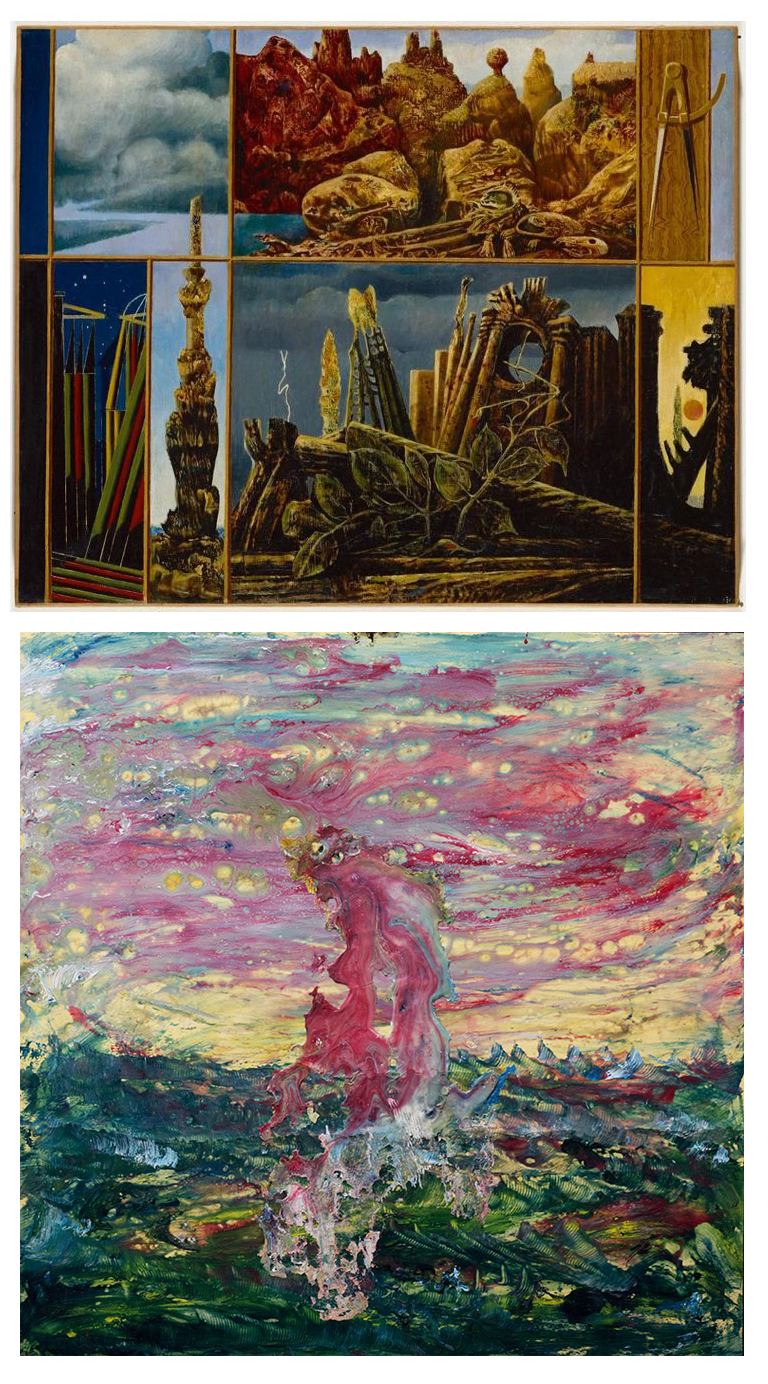

With Ernst, when you look at the techniques he used to create Painting For Young People (1943) you see decalcomania, a transfer of paint onto the surface on the large panel in the upper portion of this multi-segmented work; and grattage, a scraping away of material in the large panel on the bottom. You see similar look in A New World (n.d.) by Bartman, only in Bartman’s painting the resulting appearance of the top, where you have the organic swirls of color, is more the result of a chemical reaction relative to the incompatibility of materials used, than it is the chance blending of a somewhat blind transference of medium. And with both artists, there is the addition of facial features to personify the humanoid forms that inhabit these paintings giving some the impression of a lost soul in a threatening space.

Overall, and despite the similarities to artists that have come before him, the art of Bartman is striking and powerful and worth much more attention than he has garnered to date.

In the same room of the Bartman paintings you will find the mood-laden paintings of Laura Von Rosk. Her landscapes are also rather intimately sized, as her intended visions look like they might reside in a cleverly crafted storybook, albethey dark at times, as her representations often beg narration.

In the front room as you first enter the museum is a circular space with six built-in vitrines. Each one of the display cases hold large sheets of paper filled with delicately drawn, subtly abstracted shapes that are clearly informed by nature. In each instance, Randy Orzano offers us his collaboration between himself and the bees he keeps. By placing his completed drawings flat or folded into the very beehives he tends to, Orzano gathers the residue of an orderly and purposeful social network. As the busy inhabitants eat away at and add wax and propolis to the hive and the bordering artist’s paper a new curious design takes shape that enhances the works on paper, while maintaining an indelible link between the artist and the industrious engineers.

Featured in the large main room of the museum is an exhibition titled Arirang Grace – Between Dislocation and Settlement. All of the 16 artists in this exhibition are Korean and all are quite different in their use of materials and intended message. The loan North Korean Artist is easy to spot. Kun Hak Ri’s Rope Skipping (2003) shows a group of five children jumping with joy above a flower laden rope painted in a style that is both ideal in its representations and over-the-top in its positivity.

Bong Jung Kim, one accomplished artist whose work I have come to know quite well, offers a new series of figurative works constructed of fragments common to our fast-paced, ‘everything-is-quickly-outdated’ conditioning. In his longtime quest to project his addictions and obsessions, Kim bares his soul each and every time he makes his art. Additionally, he is showing us that the vast and endless amount of materials that is largely and quickly considered to be junk, can be seen as a treasure trove of inspiration in the hands of an artist.

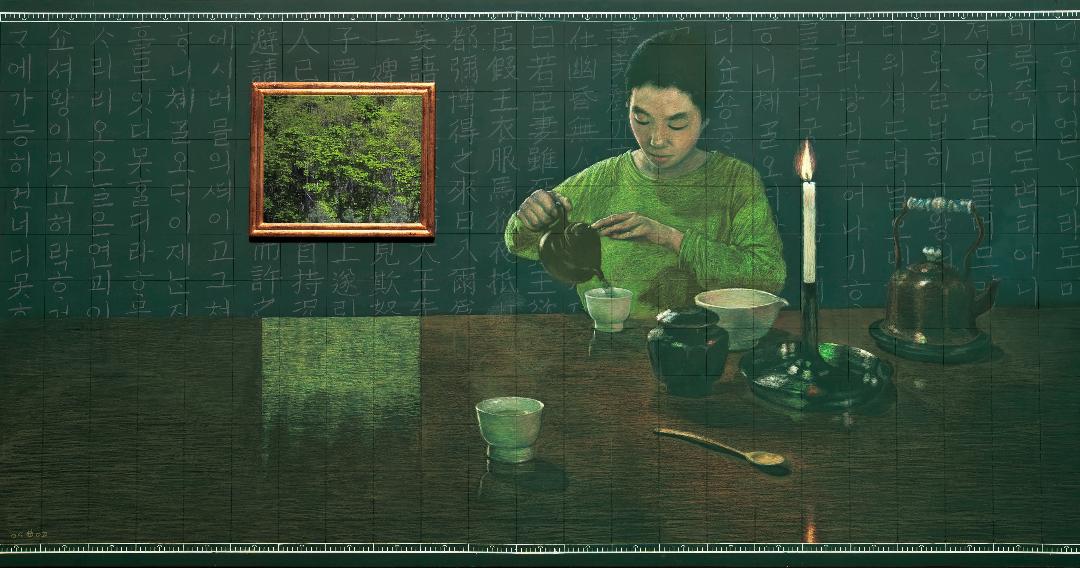

Myong Hi Kim’s Tea (2004) is a curious piece whereby the artist uses the recently abandoned school chalkboards she finds in rural South Korean towns that have lost students to the migration to cities. Working with oil pastels and chalk, and with the addition of a video of the foliage of the countryside, Kim art speaks volumes about the disappearing traditions of a simpler, more peaceful and rewarding life that is being erased by the promises of the modern era. Conversely, her husband Tchah Sup Kim opens and splays his paper coffee cup every morning in a shape reminiscent of a traditional folding fan and proceeds to paint or draw on them in various ways and in styles suggestive of his inspirations and interests. Both artists blend era and tradition in fascinating ways and both present the ages old discussion that pits the perils of progress against the tried and true qualities of life.

All three exhibitions end November 10th. There are also sculptures in various media displayed throughout the grounds of the museum by a number of artists including Joy Brown, Mimi Czajka Graminski and Tom Holmes. Thanks to the hard work of individuals like Curator Bibiana Huang Matheis, Director Lorraine Laken and a dedicated board led by its President Evelyn Tapani-Rosenthal, the Hammond Museum & Japanese Stroll Garden has maintained its pivotal position in the arts and culture of Westchester County for over 60 years.