by Steve Rockwell

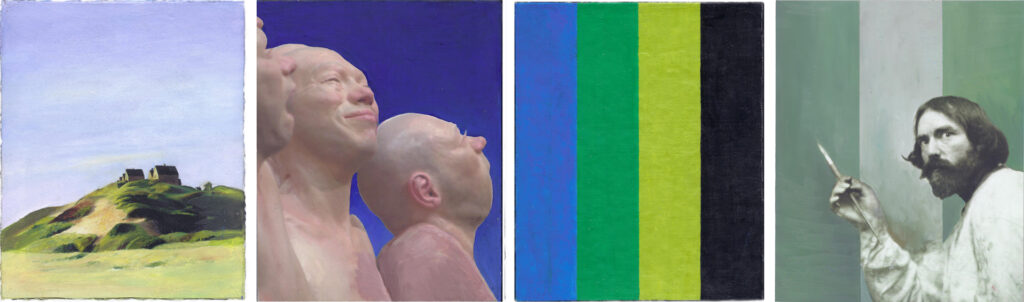

Hopper’s Corn Hill in the first panel makes use of an 1930 Edward Hopper oil that is part of the McNay Art Museum collection in San Antonio, Texas, of which I had a tour in 2005. The reproduction of the Truro, Cape Cod subject had occupied roughly the bottom half of the 8.5 x 7 inch page in dArt, which I had here expanded to the edges of the page in oils. It functions as an imaginary “framing” of what Hopper might have seen. The same device was used in the third panel, Jaan’s Divide, the original work by Jaan Poldaas, having been square, his stripes here extended to fill the rectangle. It was an adaptation to which the artist and I agreed for a dArt magazine back page to advertise his 1998 exhibition, Colours and Concepts.

The three stripes behind the image of Augustus John holding a brush allude to Barnett Newman’s 1967 Voice of Fire. The eighteen-foot acrylic on canvas had been a commission for Expo 67 in Montréal, Canada, and was part of the U.S. pavilion exhibition, American Painting Now, housed in a geodesic dome designed by Buckminster Fuller. It is not known to what extent Newman incorporated the aspect of three in Voice of Fire, aware that the work would figure prominently within a dome constructed of triangles. On principle, Jaan Poldaas would have objected this employment of the “three,” as he revealed in a discussion that contributed to a review about his Colours and Concepts work.

The image of Richard Stipl‘s sculpted self-portrait heads (panel 2), was used for advertisement of the artist’s work in the Fall 2002 edition of dArt. With the title, The Sleep of Reason, Stipl references the Goya series of aquatints, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, an attribution generally read as Goya’s acceptance of Enlightenment values, that the absence of reason invites the monstrous to proliferate. Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, a German-Austrian sculptor most famous for his “character heads” was a contemporary of Goya, who produced a series of busts with contorted facial expressions, tapping into paranoid ideas and hallucinations from which he allegedly began to suffer. Messerschmidt and Stipl, it seems, would make for a formidable art history tag team.

Five artist temperaments are featured in Curated Content #3. Though an obvious correspondence could be made between the sculpted contortions of the faces by Stipl and Messerschmidt, an unlikely pairing would be Edward Hopper and Barnett Newman. Ralph Waldo Emerson had served as life-long touchstone to Hopper, his painting output imbued with an aura of the “transcendental.” In Peter Halley’s 1982 essay Ross Bleckner: Painting at the End of History, Halley ascribes the transcendentalist wing of modernism as having its roots in French Symbolism and Emerson, informing the work of Pollock, Rothko, and Newman.

With Malcolm Arbuthnot’s image of Augustus John, on the other hand, we have a stereotype of the typical “bohemian.” It is suggested that the character of eccentric painter Gully Jimson in the 1958 Alec Guiness film The Horse’s Mouth was modelled on John.