by John Mendelsohn

The paintings of Bobbie Oliver have undergone a transformation. They have moved from monochrome to full-color, and from clouds of troubled washes to more defined shapes floating in humid atmospheres. The revolution in Oliver’s work goes beyond the formal – it is attitudinal, with the emergence of a complex of moods.

The four large paintings in the exhibition are six-feet tall, with strong passages on the left and right that open up to a central emptiness. The canvas surfaces are painted in a variety of tones, from soft pink to a range of subtly warmer and cooler grays. The grays evoke the colors of aged paper, while passages of diffused pigment suggest an affinity of Oliver’s work with the tradition of Chinese landscape painting, in which form is continually dissolving into space.

On top of the nearly neutral grounds are suspended blocky forms in fluorescent orange and yellow, and in highly saturated turquoise and pink. The forms variously recall signs of urban life such as road repairs and graffiti. There are echoes of earlier pictographic practices such as Mayan glyphs and Chinese seals.

Transparent clouds of black pigment pass over the vivid shapes like disturbing thought or diesel exhaust. The fugitive forms suggest organic life, magnified, passing across a microscope slide. Oliver’s is an improvisational art, laying down forms, flooding them with water, allowing blotted color to appear in the wash, only to dissipate.

In the exhibition are four smaller works, which share many of the elements of the larger ones. However, here they are concentrated in the paintings’ centers with a few large entities filling our view.

The overall effect of the paintings, both larger and smaller, is a kind of joyful melancholy which recognizes that phenomena arising and passing away encompass many things – the weather, the city, the art of painting, and our life and times.

Bobbie Oliver: Found Objects. High Noon Gallery, 124 Forsyth Street, New York. March 7-April 21, 2024

Dana Gordon’s exhibition of twenty-eight paintings, all from 2023, is too much. We are asked to navigate many walls of paintings that seem to slowly progress from one related mode to another. Why so many paintings? We could hazard a few guesses: the artist as obsessive completist, or as chronicler of his own productivity. Despite the challenge it may present the viewer, the best reason for the plethora of work is witness a painter’s progress – finding his way by impulse and invention, to some unanticipated place.

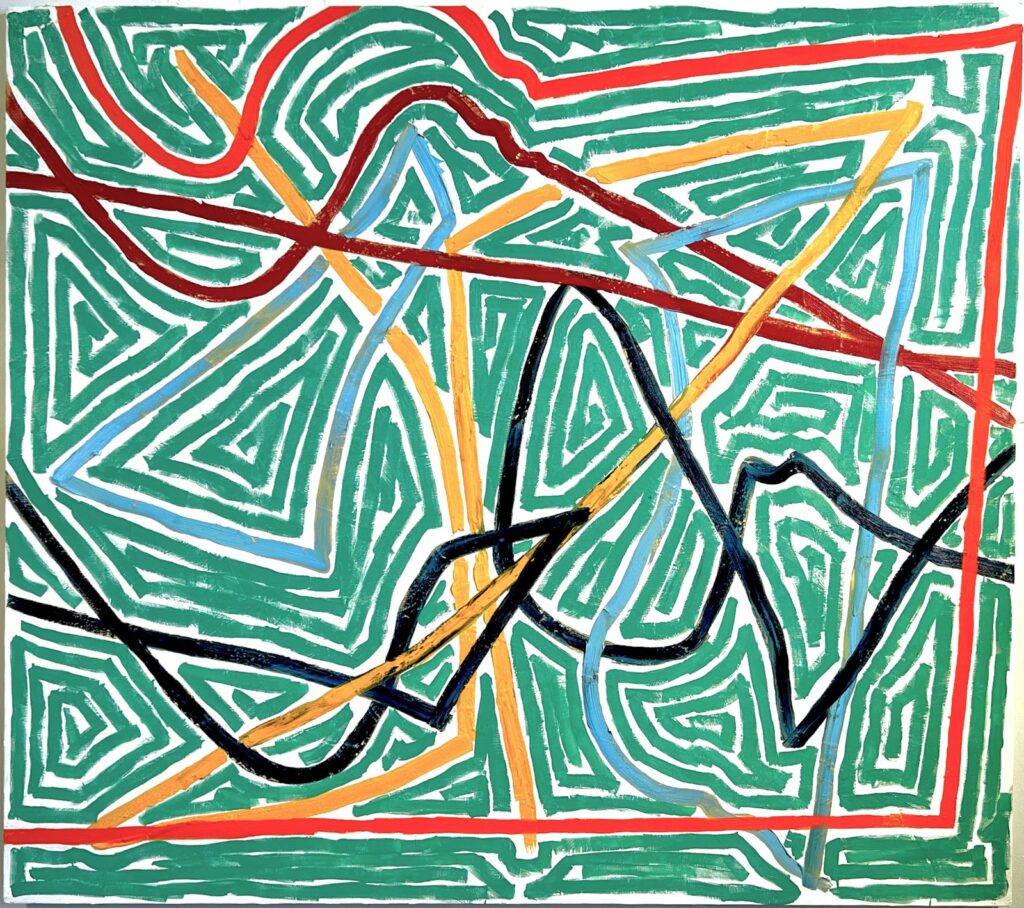

Early on, the paintings move in this sequence: first, fields of jangly, black linear gestures on white grounds, that then become arrays of colored lines, again on white. In both cases, the thick, brushed strokes do not touch, but move around each other like touchy guests at a cocktail party. These are energized, anxious marks, too charged to coalesce – distant relatives of Keith Haring’s graphic, social bacchanals.

In their next phase, the colored lines become thicker, and begin to cross over each other many times, creating a dense tangle on patterned and then solid colored grounds, suggesting an anarchic play on Paul Klee. Then something interesting happens at painting eighteen in the exhibition – the restless, impatient brushstrokes take on a new deliberateness and solidity. The structure is labyrinthine, suggesting that a path out of life’s coils might somehow be possible.

The last turn in the exhibition is the simplest and most satisfying. The layered, competing lines have been combed smooth into a new order of discrete, concentric triangular webs. Resembling plowed fields crisscrossed by diagonal roads, these final seven works have a kind of resolution that is both formal and emotional. The blunt, brash attack is still there, but it is at the service of something that feels like hard-won grace.

Dana Gordon: Signs of Life. Westbeth Gallery, 55 Bethune Street, New York. February 3-24, 2024

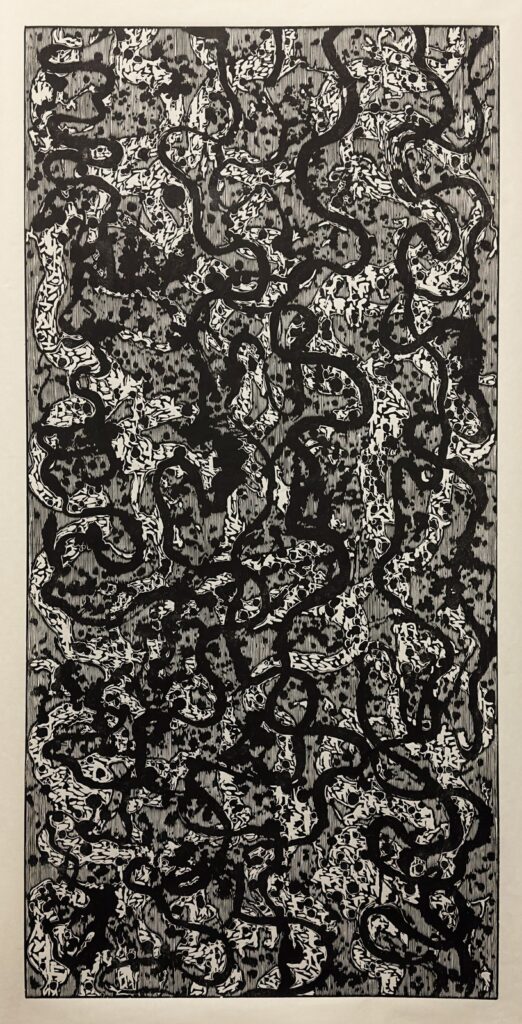

Bill Pangburn’s woodcuts, monoprints, and paintings on paper all evoke a watery world of perpetual movement. Sinuous lines suggest the liquid movements of undulating, streaming, and cascading. The fluid imagery offers a variety of ways to contemplate that which never stays still, and moves through and around the solid and the fixed in nature and in us, as well.

There are several distinct modes of Pangburn’s art in this exhibition, curated by Soojung Hyun. The large woodcuts are striking in their size and complexity. Typically, a dense ground of finely-detailed shapes or striations is riven by snaking black lines. In some of the prints, the shapes become gnarly and agitated. We sense the play of rippling water with bright reflections, and deep shadows. There is an ominous feeling that in these highly graphic images, nature is showing us how delight and danger are inextricably woven together.

In twined, large-scale reduction woodcuts, with a narrow vertical format favored by the artist, fine lines with bulbous serrations create streaming fields. Figure and ground, in black and silver, are constantly changing identity. All of Pangburn’s black and white prints, with their intense, almost narrative quality, bring to mind the appropriation of art nouveau by the graphic artists of the psychedelic 1960s.

There are three series of work that employ the arabesque. A color relief monoprint displays interpenetrating vine-like curves in mottled indigo on a field of pale lines. Smaller works with tangled lines evoke both the island of Crete, and the currents of the Hudson River.

Among the strongest works in the exhibition are three large watercolor and gouache paintings on paper. Deep blue, thick and powerful lines connect us with the Five Elements of the exhibition’s title. In the Chinese philosophy of Wu Xing, wood, fire, earth, metal, and water embody the cosmic energy manifested in nature. In these works, we feel the writhing of dragons, the labyrinths of the psyche, and the flowing waters of the world.

Five Elements: Bill Pangburn’s Rivers. Artego Gallery, March 1–30, 2024. 32-88 48th Street, Queens, New York