by Steve Rockwell

The impulse to shred back issues of dArt magazine to make pulp and paper had yielded dozens of 21 x 16 inch sheets some five years after the 2011 dArt Burger exhibition at De Luca Fine Art in Toronto. The show co-producer Ben Marshall had insisted that we install an actual meat grinder in the show, its function having been symbolic. Practically speaking, neither grinding nor shredding paper is possible with it. A basic office shredder and a uniquely-designed blender are the sole equipment requirements for dArt magazine paper production. For James Cooper’s video on the collage potential of dArt click: Dart Onion.

Steve Rockwell, Minced dArt, 2011, meat grinder with shredded dArt magazine pages and cropped magazine

A lingering colloquialism since the horse and buggy days has been the tale of glue factories killing old horses and grinding up their bones to make glue. The bubbling up of the saying, of course, arises generally in response to some human inkling of its own mortality. I sense that it might be into this very psychic cranny that San Antonio artist Hills Snyder casts his Dickensian shadow. Here is my account of meeting the artist at the 2005 Artpace Chalk It Up event in San Antonio:

“Hills Snyder arrived in undertaker black to set up his Misery Repair Shoppe, comprised of a chair and a desk with a meat grinder with which to pulverize his chalk one stick at a time. He set up shop on the Houston bridge above the banks of the San Antonio River, in itself a bit chalky from limestone, I suppose. Grinding chalk is a dry, dusty job, as is purging despair. Snyder was making a connection with the white cliffs of Dover, specifically Shakespeare Cliff, where the Earl of Gloucester, blinded for his loyalty to King Lear, took his imaginary fall, demonstrating to the ages the cathartic power of tragedy.”

More can be said about the pulverizing of chalk over the centuries. Lessons have been sown and inculcated into the fertile cranial soil of blinking pupils facing dusty blackboards, generation upon generation, stick upon stick, scratched by the stern “chalk grinders” of yesteryear.

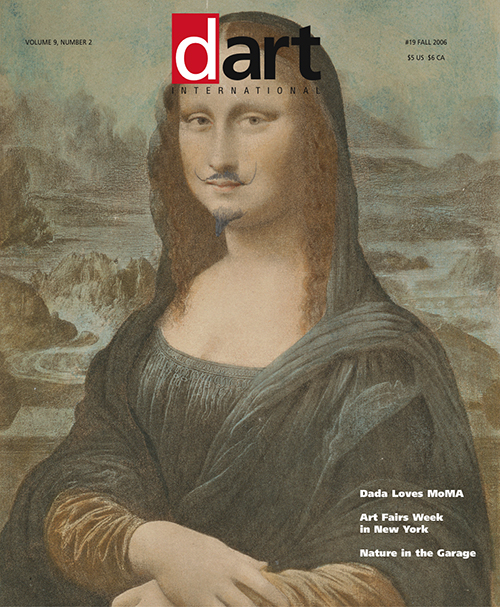

In the French city of Rouen in 1913, a young Marcel Duchamp chanced upon a chocolate grinder displayed in a confectioner’s window. The machine became the subject of two paintings, precise in the style of an engineering diagram with flattened planes, eschewing the artist’s hand. To the artist, however, its operational churning suggested something auto-erotic. Duchamp made it the subject of a major work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (1915-1923), its mechanical subject matter conversing in the language of the sexes. Frequently the artist would sign his art with his alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, or “Eros, that’s life,” as he had done with his 1919 L.H.O.O.Q. work, signifying the extent to which sexuality was at the heart of his philosophy of life.

I selected Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. as the “meat” for my own grinder, understanding that the gesture was consistent with at least one principle of Dada, the cycle of breaking and making – a shadow cast by Snyder’s chalk grinder. We all go to the same place. We all come from dust, and to dust we all return.

Above: Front cover dArt International #19 Fall 2006, : L.H.O.O.Q by Marcel Duchamp, 1919, rectified readymade of da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Courtesy Private Collection. ©2006 Marcel Duchamp /Artists Rights (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris