by Dominque Nahas

JIZI: Journey of the Spirit is an eye-opening exhibition of exhilarating contemporary shanshui style works made of ink on paper by one of the originators of China’s “New Ink Painting” school of artists, Wang Yunchan (1941- 2015), otherwise known as Jizi. Jizi was not academically trained but was an erudite self-educated individual steeped in Eastern and Western traditions of literature and painting. His own mature paintings have multiple ideational provenances. One of their origin points is a style of fifth century Chinese painting that emphasizes fantastical imagery to with mountain and water images, and are further grounded in later tradition of formal brushstroke developments exemplified through the work of landscape painter Shi Tao (1642-1707) and his canonical writings Thoughts on Painting. Jizi only became known to a wider public in the Chinese art world and beyond in the last ten years of his life, that period of production taking place in his modest studio in the Guanzhuang district of Beijing. By that period of his life he was consistently honing his works, eliminating all unnecessary elements, making monumentally dense, powerful works, “…whose large brushstrokes…” as described by art historian, museum curator, critic and the artist’s son Wang Chunchen in his monograph on Jizi’s life and art, “…made the voids seem like strokes and the strokes seem like voids.”Dr. Wang continues, “…Naturally, my father’s life was devoted to exploring his own art, but when he found a form that he believed to be his own, it was an art that belonged to China.” Such a statement also confirms my feelings about how unique Jizi’s aesthetic achievement – taking traditional ink painting, remaining true to a great degree to its originary principles, rules and objectives as written down in theses by literati masters of eons past while simultaneously taking ink-painting out of its culturally-circumscribed Asian identity and making it, somehow, come alive in a universal way to audiences in the East and West has not gone unnoticed. Jizi’s mature work took decades of devotion and intense willpower to achieve. His legacy is quite remarkably a brilliant amalgamation of traditional brush effects brought to the point of intense expressive urgency that while remaining securely rooted in centuries-old Asian ink-wash painting tradition, also tips the work into the realm of spectral imagination, into what Westerner art-historians would call romantic, even symbolist territory. Jizi’s artworks, like their ancient predecessors, are philosophical musings infused with Daoist imagery and motifs and stress the interrelationship of the human presence vis-à-vis the cosmic universe. In order to make this point such paintings have traditionally depicted tiny figures in vast landscapes (although Jizi does not included direct depictions of the full human form in any of his work;) to depict the vastness of the cosmos that is beyond human comprehension. Again, traditionally, such paintings depict natural forces by suggestively painting the landscape using a variety of naturalistic patterns, outer conditions suggestive of inner states of mind or moods, all of which invoke the way of the Dao. Jizi takes on this painterly tradition, remains true to its essential primordializing and essentializing spirit, but ramps it up, hybridizes it. Jizi has tremendous powers of invention, even wit, but without a hint of irony. Through his

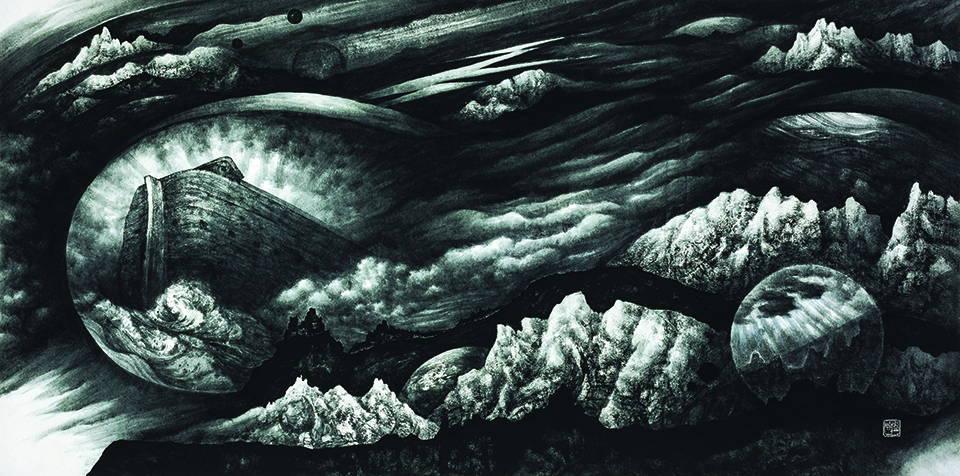

astounding brushwork he finds ways and means of anthropromorphisizing the Dao (for example using the image of the boat in Ark of Heaven of 2013, and the use of a radiant human profile set against celestial halo in Sky Aura, 2009) as he teasingly inflects transhistorical cultural Western snippets in the work. For example in Between Earth and Sky of 2009 his global landscape places that might as well be drawn from an interplanetary sketchbook one sees crenelated structures referring to the great Wall, crumbling, set against drawn the ruins of Greco-Roman pediments and entablatures. It is impossible to see such passages in Jizi’s work and not reflect on Thomas Cole’s 1837 Course of Empire: Desolation painterly masterpiece, a meditation on the forces of history and eventual disintegrating passage of earthly ambitions and powers. In many of Jizi’s later work we sense that he invokes a circulatory stream of Western influences that reverberate through his works. When we gaze at Jizi’s exalted, ferocious brushstrokes, his cascading, swirling line work that captures the interplay of voids and plenitudes we feel something ancient but also remarkably alive and pertinent to our own time, something cinematic. Jizi’s works have kinship with the mystical throbbing of visionary science-fiction movies of the like of Andrey Tarovsky. In Jizi’s paintings we feel the space age and space traveling to the infinite reaches of the cosmos just as much as we are in the presence of Ming and Sung masters of the brush and ink. Whipsawed into yet other time and space continuums Jizi’s artworks also lead us into the imaginal depths of demiurgic worlds and underworld scenes with their concomitant sensations of dread and oceanic awe in the drawings of William Blake, the scintillating glints of clouds and air in the most numinous engravings of Gustave Doré and the mezzotint illustrations of John Martin. His visual energetics that compel the postmodern mind’s eye to take in what he has to offer, which is unnervingly complex and contradictory. Jizi’s artworks are unexpectedly large–scale while his brushstrokes, depictions and compositions have an exhilaratingly fierce quality to them that bespeaks both of estrangement and deeply sonorous feelings of rapture. The apotheosis of Jizi’s aesthetic mastery and fervid complexity is embodied in his monumentally sized masterwork The Great Scroll of Dao which is 1 meter high and 40 meters long. This artwork giant scrollwork contains no images of humans but is strictly confined to multi-dimensional shifting perspectives of changing landscape elements pertaining to air, water, sky, water and rock. The Great Scroll is staggering in its complexity and rapturous beauty with passages that stun the mind with their imbricated passion and delicacy. In this work all of the varying passions, sensations, feelings, sensations, thoughts of Jizi are embodied through the application of his brush and ink on paper. In doing so he created a self-portrait of his innermost being, depicting a variety of patterns that refer and infer to cosmic and vital chi energy that courses through this, what is essentially an abstract painting that crackles with devotional intensity and psychical alertness.