by Matthew Garrison

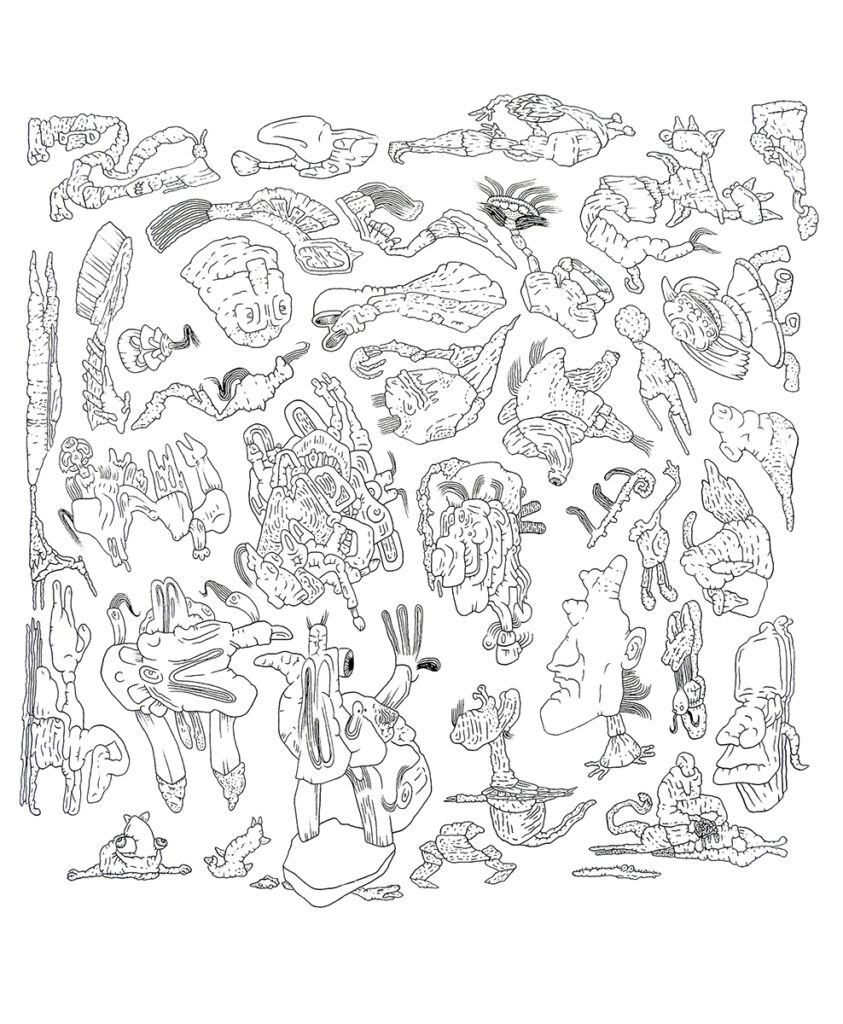

D. Dominick Lombardi’s exhibition, Cross Contamination with Stickers, at Albright College’s Freedman Gallery brings together recent work that implodes linear expectations in art by attaching a subversive cast of characters and abstract forms on stickers to paintings, drawings and objects grounded in traditional techniques and figuration. The sticker imagery emerges from an automatic drawing process where Lombardi allows his hand and mind to move freely on the page, uninhibited, in the creation of bodies, faces and amorphous forms with anatomical implications. A clue to the origins of his stickers is evident in the drawing, D-6-21, where the subconscious is accessed through a constellation of linear characters and intestinal contours. Embedded in the lines are faces, bodies and colonic forms in dialogue with one another, yet isolated in placement and spacing. The drawings might even be the dissection of a poor soul pinned across the page; each organ animated by its own disposition. While this process has its roots in Surrealism and automatic writing, it also brings to mind the drawings and distracted doodles of teens and the young at heart inspired by underground comics, animation and tattoos. The association of Surrealist history with adolescent attitudes and daydreams is further underscored by Lombardi’s use of satire and dissent in a collision of unruly worlds.

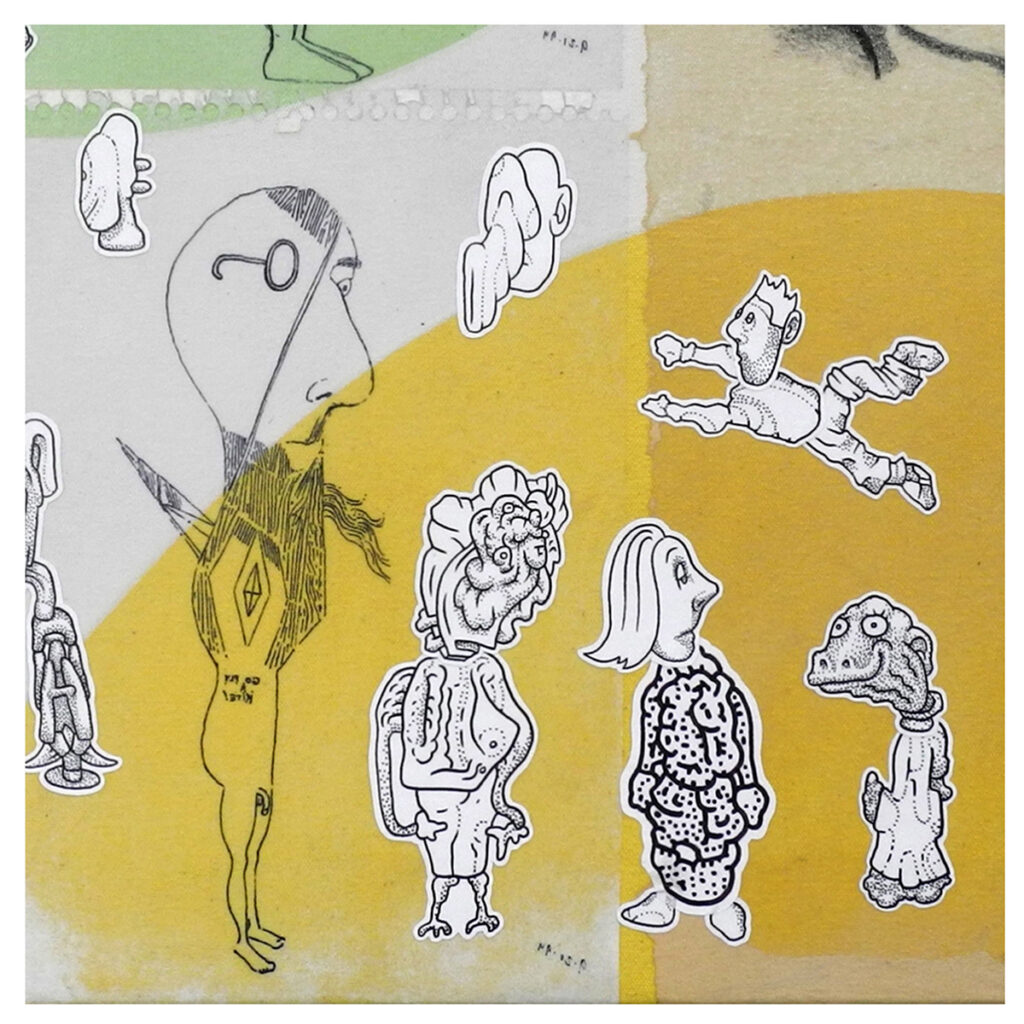

Lombardi’s application of stickers to charcoal drawings, album covers and sculpture brings into sharp contrast the disparate traditions and values embodied by their respective methodologies and subject matter. The figure drawings are repurposed from Lombardi’s demonstrations for students during his twenty-seven years of teaching life drawing. Well executed in composition and representation, they succeed in depicting the likeness and proportions of their subjects. Although, in the context of Lombardi’s work it feels absurd to look at these drawings through a formalist, academic lens. Together the drawings and stickers destabilize the histories and sensibilities behind their realization. Yes, there’s harmony in their composition and hue, but the combined attitudes and methodologies are unsettling. Lombardi negotiates an uncomfortable alliance in his work. While the figure drawings endeavor to attain classical representation, the stickers undermine these traditions with humorous impropriety; an affront to the well-intentioned studies. Both hold their own by asserting divergent values all the more apparent by their proximity.

Analogous to graffiti, Lombardi’s stickers bring to mind the “hello my name is” stickers filled in with the swirling, jagged monikers of their makers that dot New York City’s transit system. A misdemeanor tag rarely worth pursuing by the authorities, the graffiti artists interject themselves into the monotonous, engineered aesthetics of commuting. A declaration of self and markers of time, the subway stickers exist until peeled off or worn away. Lombardi’s stickers, on the other hand, tag an introductory foundations course, life drawing, pitting the traditions of proportion and representation against the raucous attitudes of underground comics.

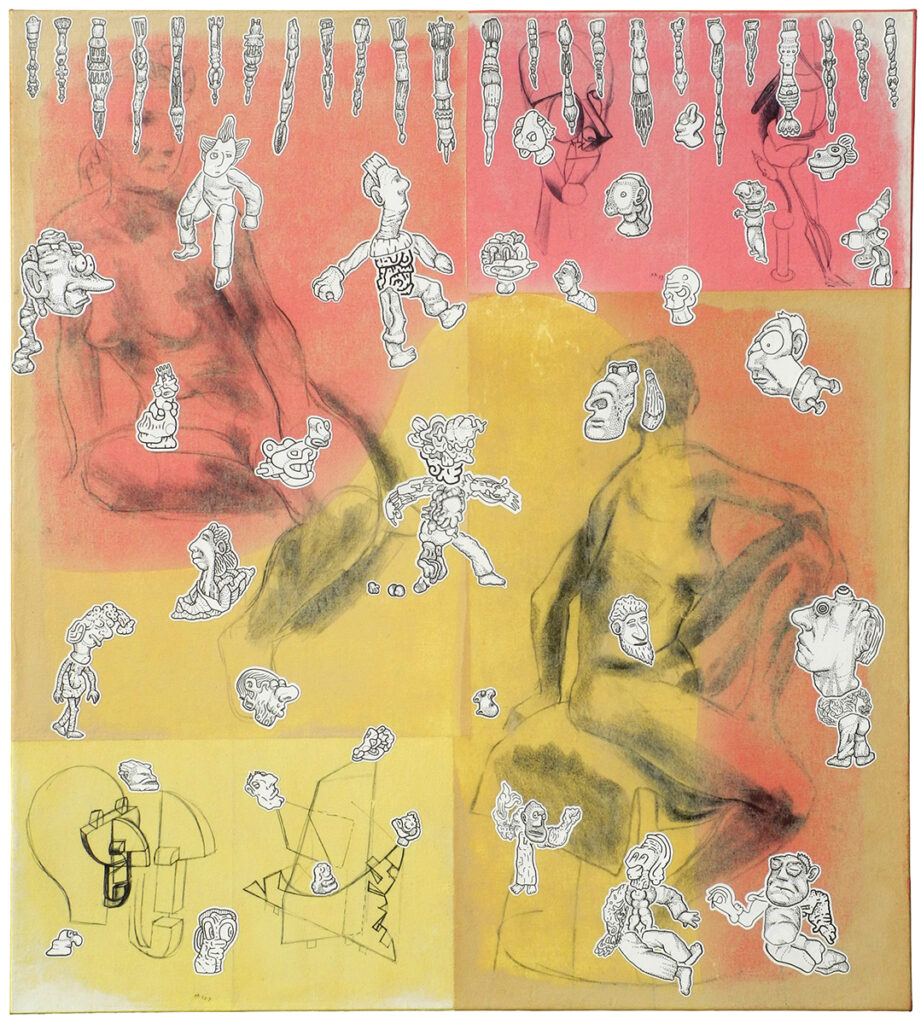

The painting, CCWS 92, exemplifies this tension between dissimilar practices. The canvas consists of six sketches interspersed with black and white stickers. Two of the six are charcoal drawings repurposed from the figure drawing classes and four are studies in marker reminiscent of early 20th century abstraction. Suspended like stalactites across the top are stickers of gelatinous mechanical forms. Throughout the canvas are Lombardi’s ill-behaved characters. Disembodied heads hover over models while exaggerated figures are in dialogue with each other and the models on fields of pink and yellow. Internal organs seem to have developed outside the bodies of some. The best artists instill their unique perspective and spirit irrespective of the subject matter. Lombardi accomplishes this by disrupting the technical origins of the charcoal drawings with stickers rooted in underground pop influences. Lombardi’s fusion of academic concerns with an alternative mindset questions assumptions around “high and low” art by presenting contradicting motivations side by side with equal authority.

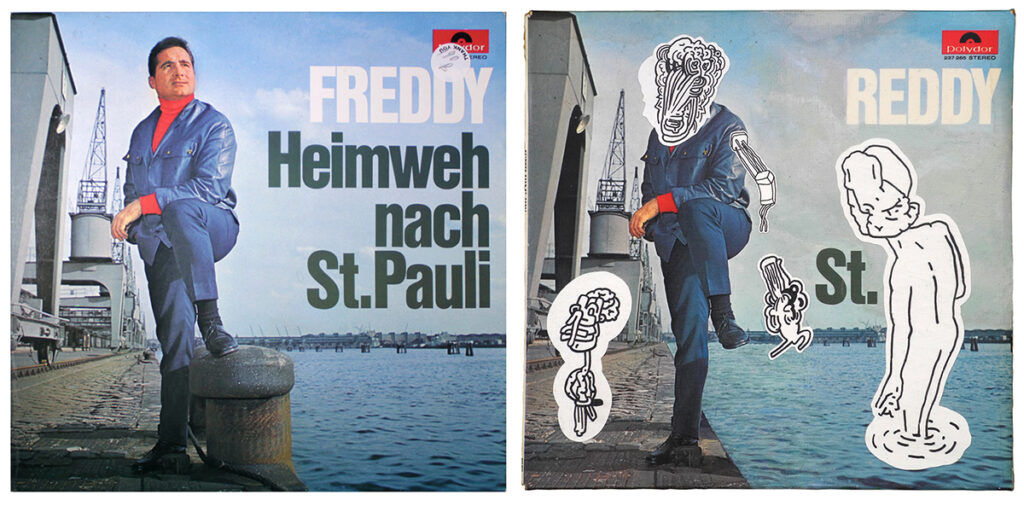

Humor is central to Contamination with Stickers. For instance, Lombardi has placed stickers in conversation with the remains of imagery and text on album covers. The wit in this work not only stems from connecting disparate aesthetics, but also from his seamless over-painting of elements on the albums. The humor is subtle, labor-intensive and easy to miss. There’s no Photoshop to assist Lombardi with the detail and time required to remove by hand all the text on a Barry White album, or text and a section of the dock on a Freddy Heimweh cover. Lombardi’s modifications separate the artists from their personas. Instead, Freddy Heimway is reenvisioned as “Reddy St.” and the faces of both are covered with stickers. Now unrecognizable by most, the album format remains while promotional expectations are subverted with irony and finesse.

The most audacious piece in the show is the freestanding painted assemblage, CCWS 25. Visitors to the exhibition openly laughed when confronted with its punchline, a rare reaction in the polite confines of an art gallery. The armature of the sculpture consists of plastic bottles from various products and discarded wood objects embedded in a biomorphic paper mâché arrangement. Although the bottles are no longer visible, their origins reference ubiquitous plastic waste and determine the shape of the sculpture with implications of mutation and survival. A table leg serves as one of its legs and the rounded end of a wooden spoon is recast as an ear. The proportions of the sculpture are reminiscent of a teddy bear except here the creature is headless with ears protruding from its torso. A green and yellow appendage in the form of a grapefruit is attached to its side. Stickers of abstract designs punctuate the sculpture. CCWS 25 seems to have taken shape from one of the stickers on a nearby painting.

The sculpture greets its guests with a cheerful, positive demeanor. Its pudgy proportions and stickers function as a comedic buildup to the sculpture’s posterior. Moving around CCWS 25 reveals a cherubic figurine with its face buried in the creature’s buttocks. The discovery is jarring and unnerving. Most will respond to this encounter by recoiling, laughing or both. The conditions are difficult to discern and impossible to ignore. This might even be interpreted as an investigation into sensory deprivation and teamwork. The figurine with arms wide open does not appear to be distressed and, perhaps within the conditions proposed by Lombardi’s exhibition, is in an amenable and unremarkable situation. It’s as though the figures in CCWS 25 and throughout the exhibition need each other to navigate the intractable worlds they inhabit.

This is where the collision of ideologies in Contamination with Stickers is most subversive. Assurances found in taking sides are called into question. Lombardi destabilizes bias in the exhibition by composing dissimilar characters, values and forms into harmonious pandemonium. Discomfort with the show most likely arises from the assumptions and predilections projected onto the work, while the work itself remains confident in its lively exchange between high and low aesthetics and ethos. Meanwhile, the characters and figures sourced from personal history and internal realms remain in buoyant conversation – happily indifferent to outside decree and assessment.

D. Dominick Lombardi: Cross Contamination with Stickers runs through December 8th, 2022 at the Freedman Gallery, Albright College, Reading, Pennsylvania.