by Jonathan Goodman

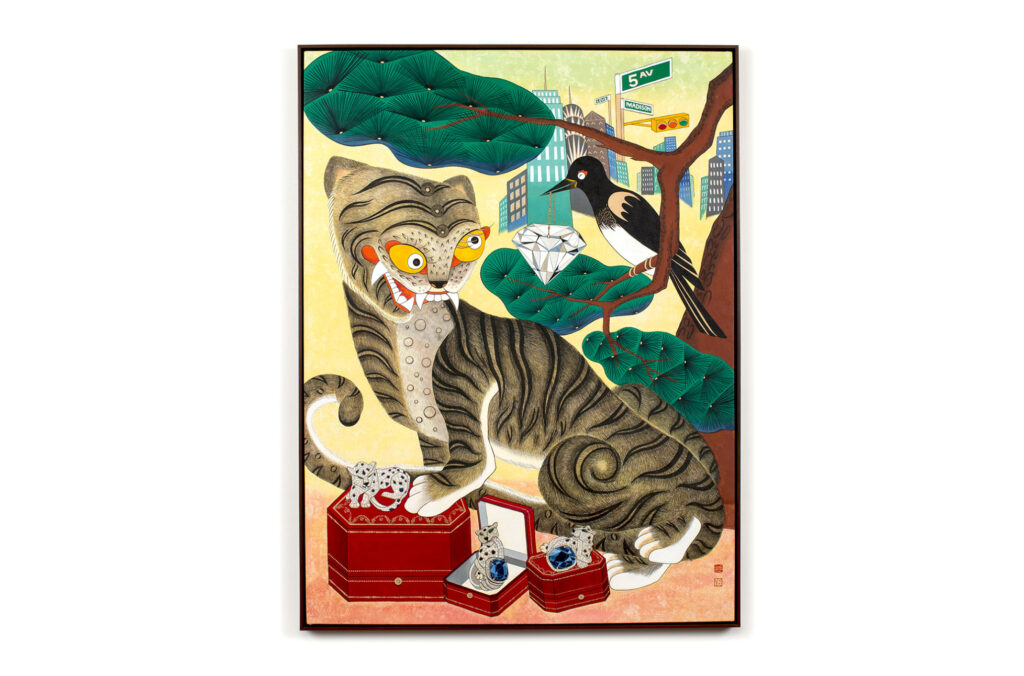

“Ouroboros,” the solo show by Korean-born, New York-based artist Stephanie S. Lee, can best be described as an amalgam of influences. The Ouroboros, an image of a snake swallowing its own tail, dates back to ancient Egyptian and Greek mythologies. It symbolizes eternity and is wholly associated with Western culture. At the same time, Lee regularly uses the minhwa, or folk art, associated with presenting traditional Korean narratives, wishing and sharing good fortune and well-being among commoners in everyday life. In such work, traditional animals – tigers, dragons, and magpies – appear in the midst of modern New York City. Lee, a highly active resident in her community, to the point of having her own gallery called The Garage Art Center (www.garageartcenter.org) (her garage transformed into a showing space!), shows artists from around the city. Besides curatorial, design, and teaching Korean folk art, she paints regularly and considers herself an active artist. This show, very nicely installed within the spacious Town Hall gallery, indicates Lee’s sense of received form and an ongoing belief in doing good things, as demonstrated in her involvement with other artists and the community.

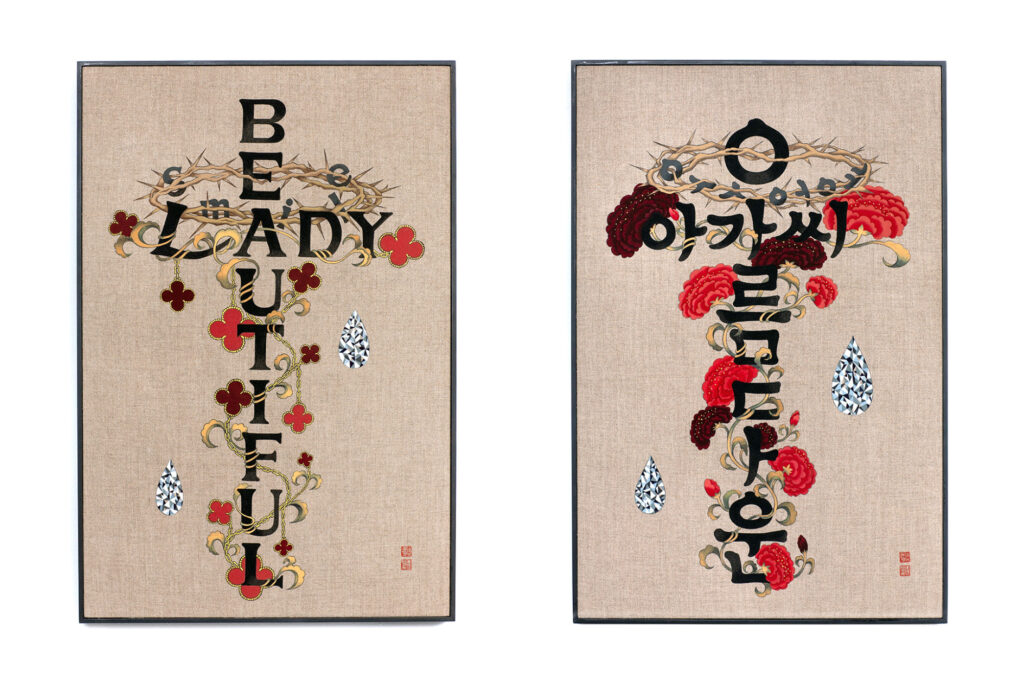

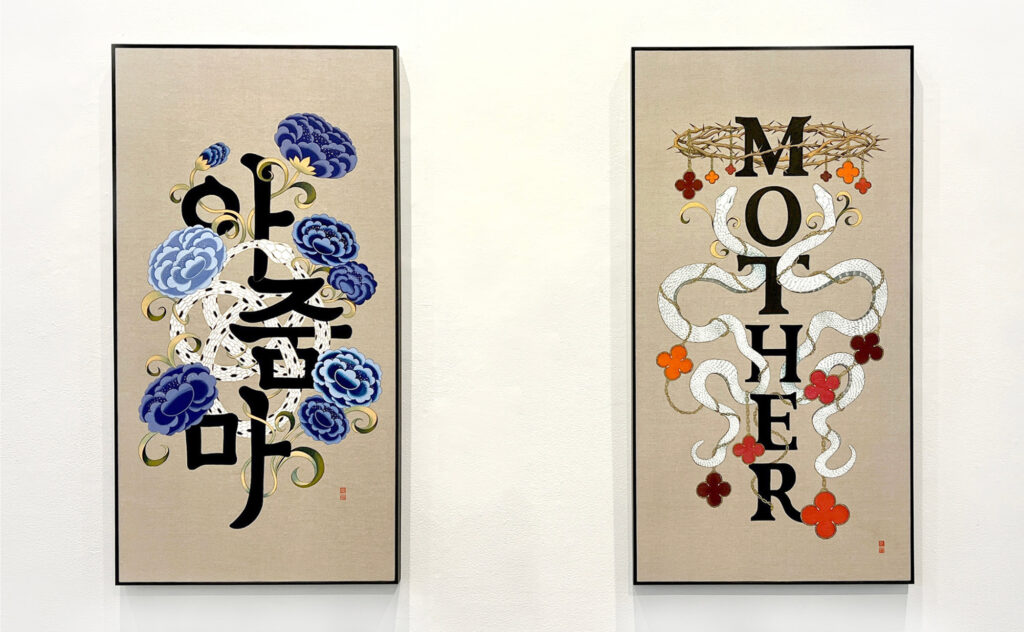

In this show, Lee combines Korean and English letter forms with images such as traditional animals, diamonds (a symbol of pure goodness that overcame hardships), or Ouroboros (the symbol of eternal destruction and reincarnation).

This series depicts her journey to finding happiness and hope while going through repetitive everyday life as a mother, wife, and middle-aged female artist. A good deal of the work in this show consists of diptychs with Korean characters, usually expressing Confucian terminology in one painting, which is then accompanied by a second, often spelling out the meaning of the Korean language in English. Other works of art include characters depicted on black diamond-shaped faux leather canvases or hanging scrolls. In her wish to merge imagery, textual references, and a nearly palpable sense of moral integrity, Lee is pursuing a language that owes its depth to Korean thought despite having lived in New York City for two decades.

Korean life in New York City, both in Manhattan and the outer boroughs (especially Queens), often determinedly remains Korean. Yet, inevitably, the city’s social structure and international culture makes its impact on all foreign cultures, no matter how insulated its immigrant inhabitants may wish to be. Certainly, this does not describe Lee’s own outlook. Instead, she embraces the diversity of New York City, even as she relies on the suggestion, sometimes overt and sometimes not, of Confucianism and Christianity for an approach to life and art. Lee studied graphic design for her BFA in Brooklyn and Museum Studies for her MS in Manhattan at Pratt Institute and learned folk art painting at Busan National University. Her work in school is reflected in her art; her paintings are exquisitely designed and are usually rendered in the naive style of the folk art she follows. In her ‘Munjado’ (Pictorial Ideograph) series, English alphabet and the Korean lettering is beautifully expressed, being indicative of the calligraphy of both culture she experienced.

Given that her art, inspired by folk tradition, reintroduces a historical Korean tradition, Lee’s work travels a long distance, both geographically and culturally. But Lee’s message is hardly antiquated; her work shows a very good sense of contemporary design and thought. On one wall, facing the viewer walking into the show, three pieces occur: in the middle, we see a large hanging scroll created in 2022. Its twisting, vertical shape establishes the symbol of infinity, with its mouth grasping its tail near the top of the hanging canvas. There are the words “useless” and “unproductive” in Korean on each snake, representing unanswered questions to herself on why she keeps creating artwork despite hardships. The symbol’s center is an open sphere created by the curves of two thin, interwoven Ouroboros, held together in the middle by a horizontal circle. On either side is a black diamond, serving as a background for single words. On the left, we see the neon-lit word “Value” in a script, and on the right, we come across the word “Art,” also in neon and written in script. When Lee presents the word “Value” on the left work, she clearly intends for the word to be understood in a non- commercial sense. (But Americans, accustomed to the economic worth of things, may take the term differently.) Her use of the word “Art” is universally understood in a moment. As for the Ouroboros, the snake symbolizes infinite possibility–from a Western point of view.

Lee is giving the nod to different traditions as she works. It can be asked if the incorporation of Western mythology with the Asian folk imagination is a bit awkward; my own feeling is that, in the case of the work discussed in this show, Lee’s strong skills in design allow her to make use of the different cultures. She incorporates the imagery that is familiar to her into a vocabulary of her own making. The piece called Ajumma (2022) of the Korean characters

meaning ajumma, which in English can be understood as a married or a middle- aged woman. In Ajumma, Korean writing is intertwined with a snake made out of gems, while on the periphery of the image, several peonies, in dark or light blue, ornament the composition. In the painting Mother (2022), the word “mother” is presented in capitals and is less difficult to see. On either side of the English word, two white snakes, vines circling their bodies, mirror each other’s curves to form the shape of a uterus. On the lower half of the snakes’ bodies, luxury jewelry in reds resembling the color of blood is hanging, while at the top, a crown of brown thorns is also decorated with them. Religion is strongly followed within Korean life, and the artist agrees with both Christian and Confucian thought.

Animals like tigers take up Lee’s imagination, as the artist remains devoted to the minhwa style and themes she admires. They represent strength and power and are perceived in a supernatural fashion as a guardian spirits. It is exceedingly hard to take a folk art theme and contemporize it in a way that does not do damage to the subject’s original implications. Sadly, we are living in a time when human overpopulation and subsequent development of natural lands are depriving wild animals of their habitat. But the large cats remain large in Lee’s imagination, often standing for human virtues that remain as guides to bravery or even a heroic stance. In the tigers I have seen portrayed by Lee, their fierce vigor is softened to some extent by the artist’s affectionate presentation. This does not mean that Lee is giving up on the tiger’s reputation for ferocity, only that within the folk tradition she is following, the animal is usually represented as less wild and friendly. So Lee’s representation is gentle and humorous rather than fierce. In her tiger paintings, she may be closest to the Korean imagination.

There is a question implied by this show: Can Lee’s audience, either Korean or non-Korean, be able to effectively appreciate the painter’s merger of cultures? Can a crown of thorns coexist effectively with a folk rendition of a Korean tiger? Is the Ouroboros an image dispersed widely enough that it would make sense to Lee’s Asian followers? These questions might come close to taking over the real achievement of the art. Yet Lee’s visual skills, her adept use of both Korean and English words to complicate her message (in a useful way), and her unspoken insistence on principles provide her with the means to surpass the difficulties of a hybrid existence. In the poster announcing the show, the words “Mother, Wife, and Artist” are prominent, indicating the several roles someone in her position plays. Here the language is not politicized; rather, it is descriptive of a modern woman’s life. “Ouroboros” is of high interest not only because Lee merges influences but because she has dedicated herself to image-making despite the pressures of her daily activities. It is a good thing she pays so much attention to her art, which rewards its viewers with both visual elegance and honorable consideration.