by Steve Rockwell

The use of planes, trains, and automobiles are required to get to the place where this article might take us. The cultural product being shipped has triangulation points between New York, Toronto, and the town of Belleville, Ontario. Its cargo designation comes under late minimalism, set in motion here by the Bellville artist collective K8N, and arriving at their Gallery 1313 exhibition in Toronto last November, in all likelihood by automobile. Belleville exhibitors Steve Armstrong and Elizabeth Fearon were joined by the third K8N member Toronto artist Rupen, to produce a thoughtful, cohesive show.

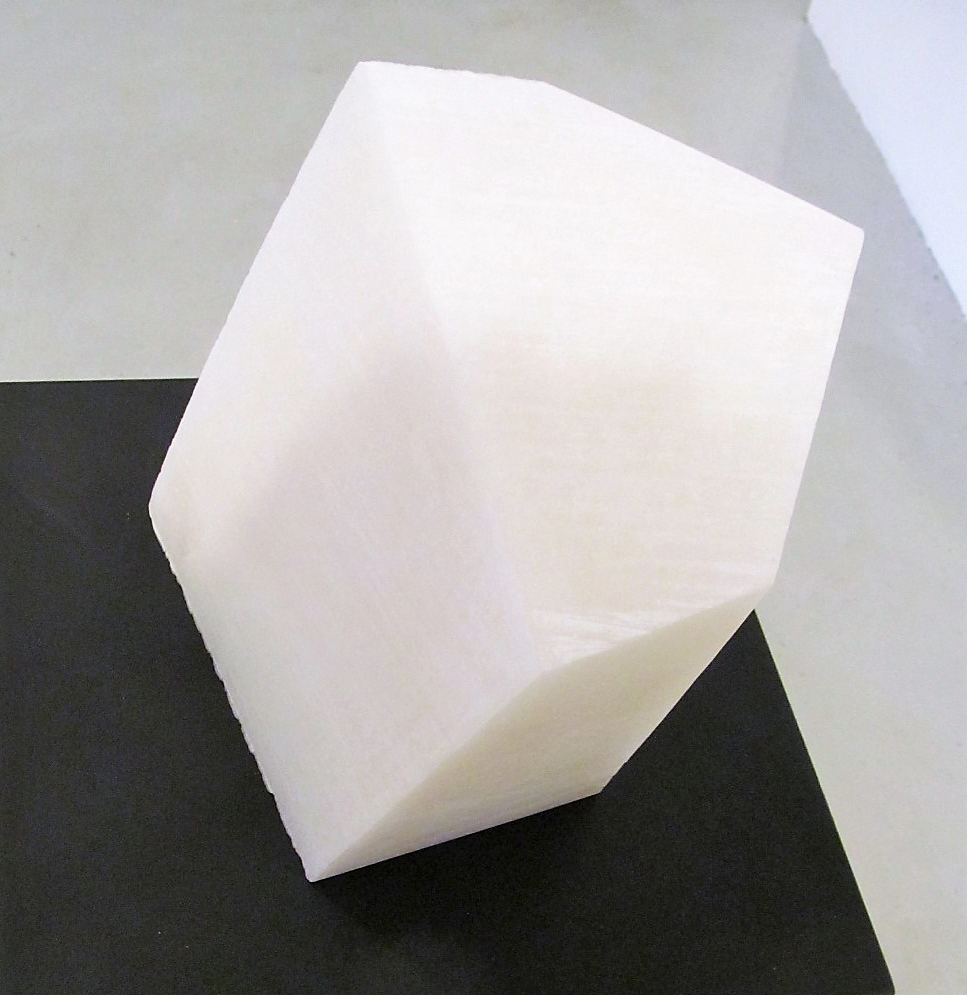

The divergent aesthetic concerns of Armstrong and Rupen, displayed on the walls of the gallery, knit nicely together into a “body of work” helped by Fearon’s six stone sculptures on plinths, which cleaved the show space like the vertebrae of a spinal column. A self-evident human scale gave primacy to the hand of the artist, the burden of meaning falling on the materials employed and their craft.

Some time after beginning my deliberations on the K8N exhibition, I boarded a jet for a winter holiday. To get to the gate at Toronto Pearson International Airport required me (or rather I chose) to walk through Richard Serra’s “Tilted Spheres.” Having previously looked “at” a work of art, I was compelled here to reconcile being an observer “within” a work. Serra’s massive steel forms were carted from New York, where Richard Serra is based. Toronto has a large art scene by Canadian standards, but New York’s is large globally. By this token, Belleville has an art scene, perhaps proportionate to its population of under 60,000, of which the K8N Collective is a part. My own journey in art matches this hop from small to large, with the international ethos a shifting point of reference.

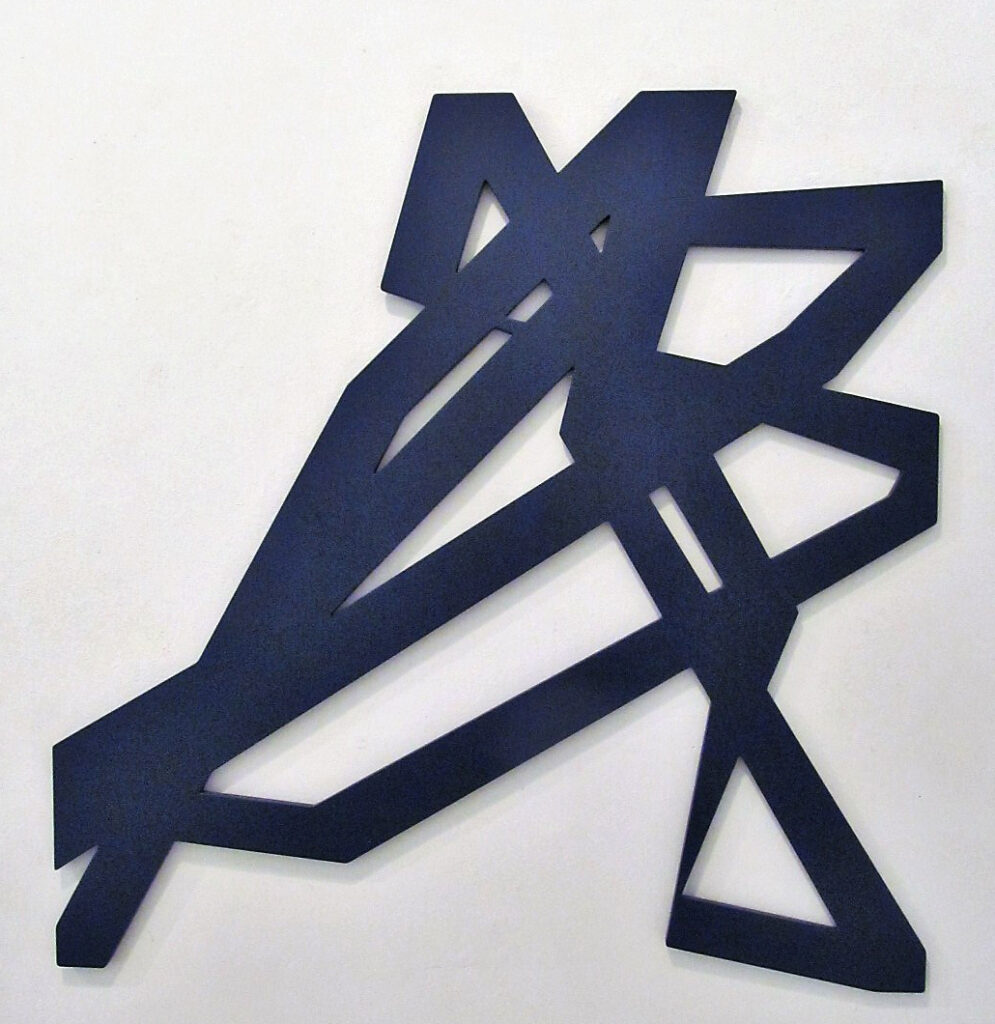

This fabric of geographic connectivity is the soil out of which much of the art which is presented to us grows. In 2004 Rupen exhibited a series of wall works in wood, beige panels with networks of red lines inspired by railway tracks leading in and out of “the great art cities,” such as New York and Paris. My first exposure to the K8N collective was at Rupen’s show space and home in the Junction district of Toronto in 2019, very nearly where its four lines of track intersect. The K8N name itself is the postal code designation for Belleville. The environment and how the body situates itself within it, has a part in the making of Rupen’s art, who employs a process of distillation that includes a subtle playback loop with each creative adjustment. Rupen views the body as the recipient of life-affirming energy, that is released in the making of each work.

Fearon’s 1997-03 photo-booth work explored the movement of face and body, having led the artist to considerations of the framed capture of an individual in “official” uses such as passport photos and other licensing protocols. Isolated frame demarcations that form grids apply not only to our immediate urban environment but engulfs the entire globe ultimately. Information networks structure the flow our personal data electronically much the same as air, sea, and land transport does physical counterparts, both synched to their respective red and green lights. These considerations situate the patiently filed facets of Fearon’s stone sculptures within a dynamically alive environment, while the objects themselves evoke a stillness. Each surface performs a sublimation, condensing and purifying all that it absorbs as the work progresses.

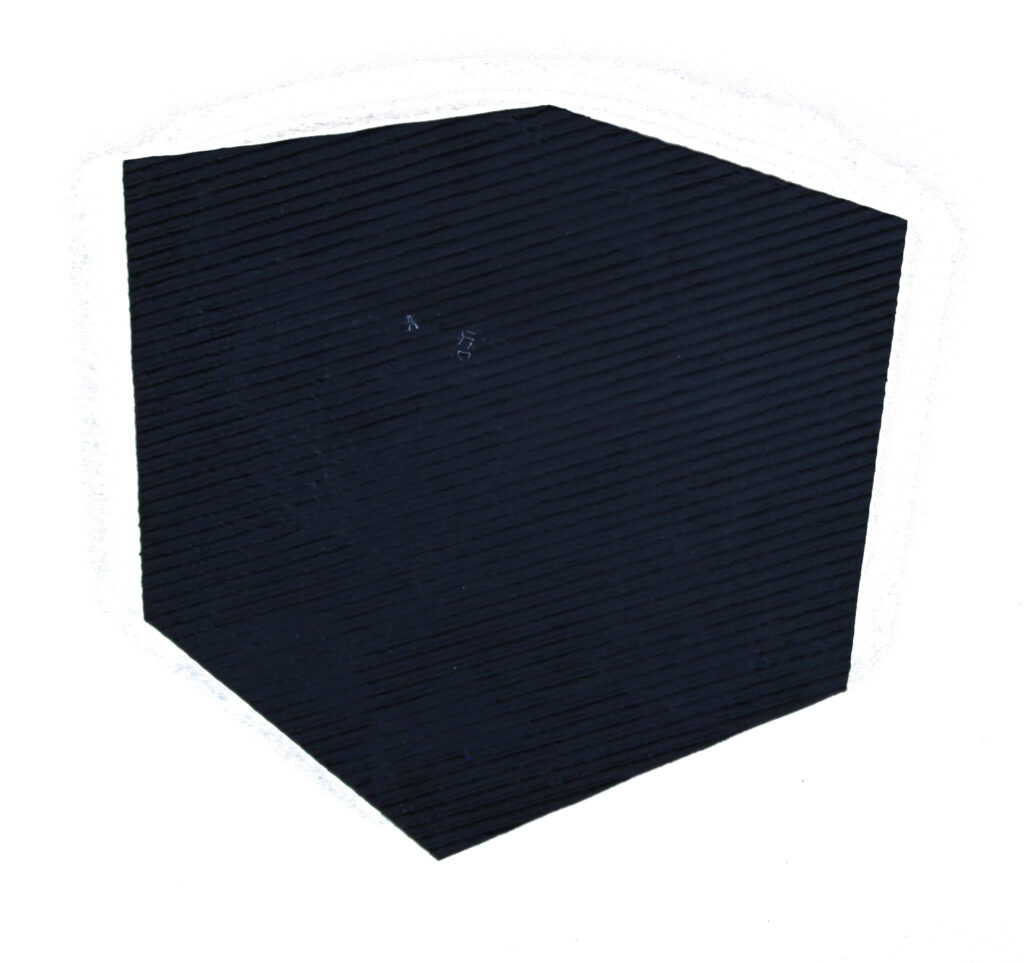

Surface ambiguity has been an abiding interest to Armstrong, much of his work designed to read as second and third dimensions simultaneously. This playfulness is welcomed in art, but not so much on subway platforms, elevator shafts, and edges of cliffs. Getting the gestalt of what we see around us is obviously important to our survival. Distinguishing the illusionary in our art may serve as helpful training wheels for the real world. We also accept Armstrong’s sly sophistry that drilling a hole in an object doesn’t yield an interior, only more surface. Worms, on the other hand, understand that boring through the skin of an apple doesn’t yield yet more skin, but pulp, something materially different from the apple’s surface. This focus of Armstrong’s art on the nuances of visual perception and the language that we employ to describe it, packs our daily “spectacles” into the retinal arena of our eye – a kind of microscopic Roman coliseum.

The funnel of all fabrication from the hand-manipulated to the mandibles of an industrial-sized forge, channel our compressed experiences through the wires of a common neural network. Viewer and artist tap into the same channels. The twelve meter steel walls of Serra’s “Tilted Spheres” at Pearson Airport close in over heads, and we experience its potential crush in our gut. It makes palpable the cabin pressure in the hull of the jet that we don’t feel, but know is there. The congestion of an urban grid, and its electronic counterpart carries its own crush, which Feoron somehow eases with the honing of her alabaster facets. The filing of the stone subtracts to reveal its material beauty. In the ordering and reordering of the folding ribbon of planes in his “Rebounding Energy” Rupen plays the scales of line and plane to elicit “sound” from a mute form. The fundamental question that Armstrong raises is, “What can I come to know about the object that I see, if what I sense from it is a contradiction?” Whatever the scale and scope of the object in our vista, the neural bandwidth that equips us all is essentially the same.