by Steve Rockwell

Shirin Neshat has super-powers, not unlike those of the DC Comics super hero who fell to earth in a rocket launched from the ill-fated planet Krypton. Like Jor-El, the father in the Superman story, Shirin’s father “saved” his seventeen-year-old daughter by catapulting her to America from the failing regime of the Shah of Iran before it imploded. With the Ayatollah Khomeini subsequently in power, everything changed for Neshat. Cut off from her family and roots, she was made an alien in a strange land.

The changes that Neshat observed of Iran’s political and religious upheaval upon her return in 1990, were both “shocking and exciting.” This new ideology had transformed the country’s culture in both appearance and habit. Her 1993-97 series “Women of Allah” gave expression to the inherent militancy that had infused Iran’s Islamic fundamentalism. This work signified the breaking of the dam of emotion built up from childhood of an inner dichotomy between her non-religious upbringing amid a conservatively religious Iranian town. She recalls having had tea in her garden as a child, and bursting into tears at the sound of quranic chanting.

“Women of Allah,” infused Neshat’s work with a power that generated immediate success. At the same time the artist faced a flood of criticism from many sides. To the Islamic Republic it was anti-revolutionary, while the people of Iran thought it supported the revolution. Western critics felt it sensationalized violence, and took advantage of the controversy surrounding Islam. Feeling misunderstood, “Women of Allah” became a turning point for Neshat. It began her journey from an overtly political or religious art to the mythic and allegorical. While retaining its Iranian themes, “The Land of Dreams” exhibition signifies a completion of the transformation of Neshat into an American artist, reflecting her own displacement with those of other cultural minorities and disenfranchised at the country’s margins.

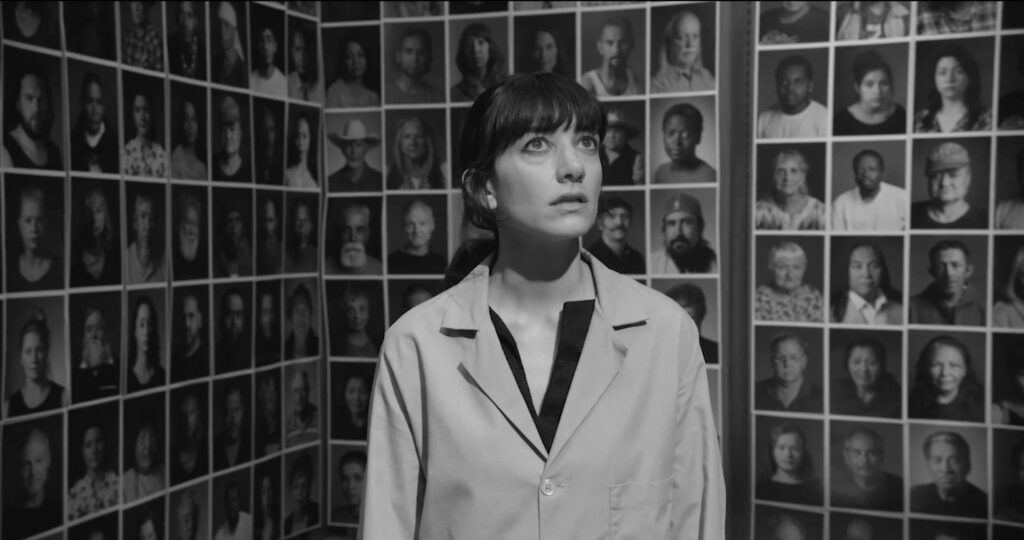

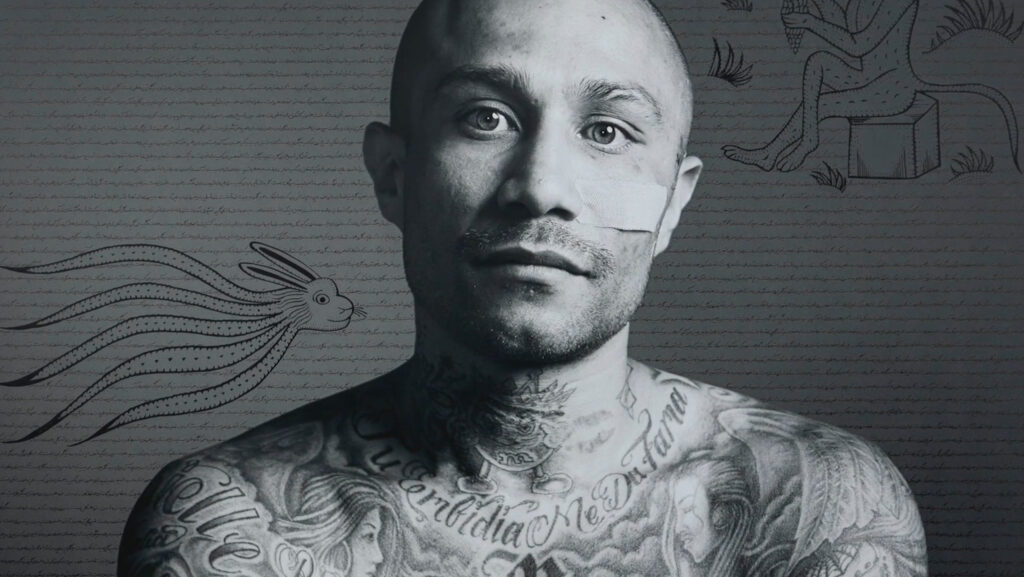

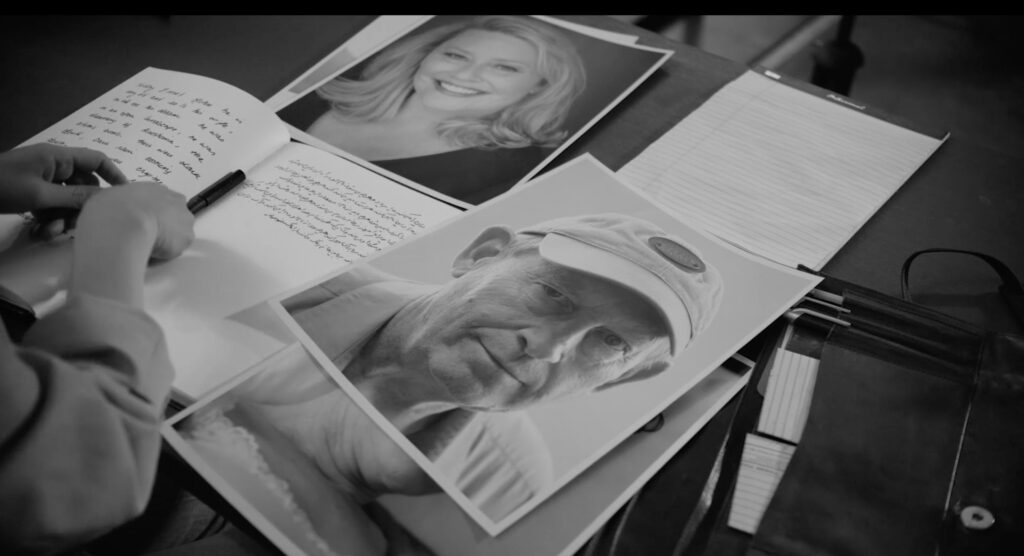

“Shiprock,” mountain in New Mexico was selected as the mythic site for “The Colony,” while the actual filming of the inhabitants took place in a power plant. The crew had been scouting for a dark, claustrophobic setting for the paper-pushing bureaucrats, but were delighted with the atomic bomb-facility ambiance of the power plant. Here, rows of lab-coated dream catchers could quietly go about their business of cataloguing and analyzing the dreams of the residents of a nearby town. It took a week to cast and photograph the actual 200 New Mexico residents from which the photo-based component of “Land of Dreams” were drawn.

Sheila Vand plays the part of a photographer who plumbs the dream world of the town’s people at the behest of the Iranian authority figure that leads The Colony. In a scene set in a darkroom we see her reflection meld with the face of her subject as it materializes in the bath of the developing tray. Vand’s character has entered the dream of another – a violation that carries with it the punishment of an inevitable loss of identity and the pronouncement: “The dream catcher will go mad.”

The “Land of Dreams” project was conceived as Neshat’s response to the collapse of the Iran nuclear deal that came with the transition of US administrations. Trump’s tenure had immediately ramped up hostilities and tension with Iran. The artist felt that “something had to be done.” The shadow of something falling over the world stage with which Neshat is only too familiar has crept in like a fog. Now her dichotomy of alienation is being played out in the country of her adoption, with the scale of the stakes much higher.

If the channelling of the quranic chant of a Muslim woman multiplied a thousandfold lent Neshat an expressive super-power some 30 years ago, how will this energy bottled as myth and allegory play out in America’s vast “Land of Dreams?” As the political pillars of power are being shaken globally, should the chord of polarization snap, it might be good to know where some of that kryptonite is likely to land.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto (MOCA) Shirin Neshat exhibition runs through to July 31, 2022