by Steve Rockwell

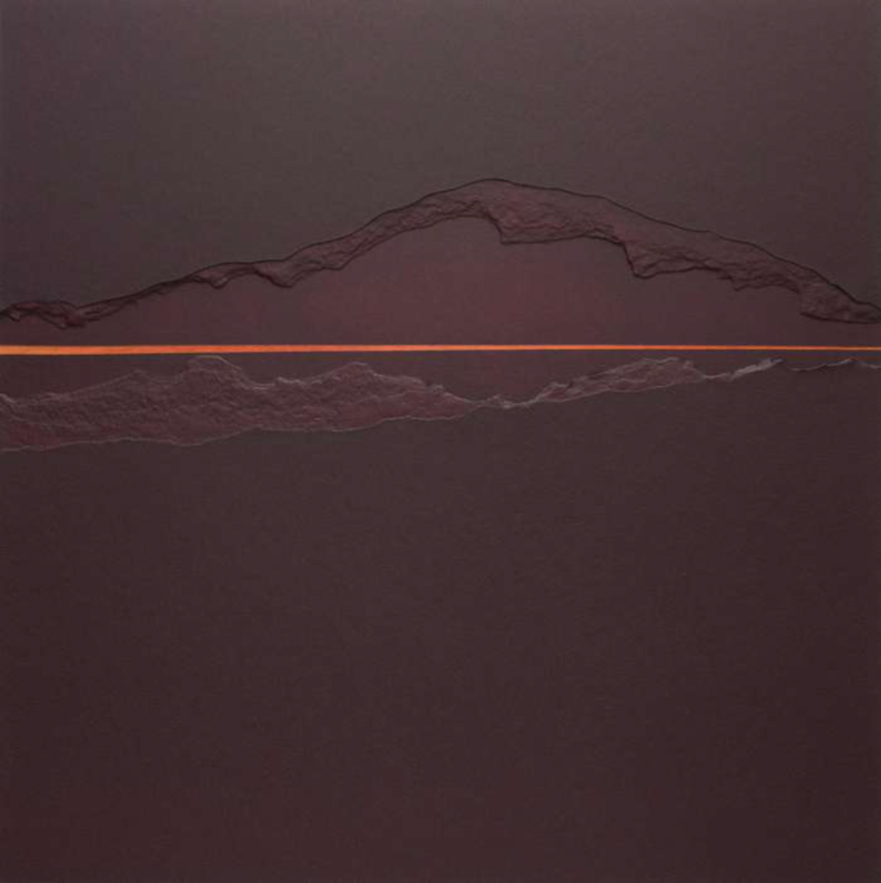

At the artist talk for his “You see it” exhibition at the Christopher Cutts Gallery in Toronto, Pat McDermott emphasized the direct experience of his work as a key to unlocking its import. The artist avoided references to contemporary art criticism, but elaborated on the Lascaux cave art as his primer. Although interpretations of pre-historic cave art will likely be subject to our own prejudices, there is a belief that ritualistic trance-dancing may have been part of this early art, shamanistic rituals inducing visions. Cambridge professor of classical art and archeology, Nigel Spivey, points out that the dot and lattice patterns overlapping the representational images of animals resemble the hallucinations induced by sensory-deprivation. Regardless, we can infer that the Lascaux artist communicated to the cave community directly and powerfully, to the extent that their lives somehow depended on the reception of its message.

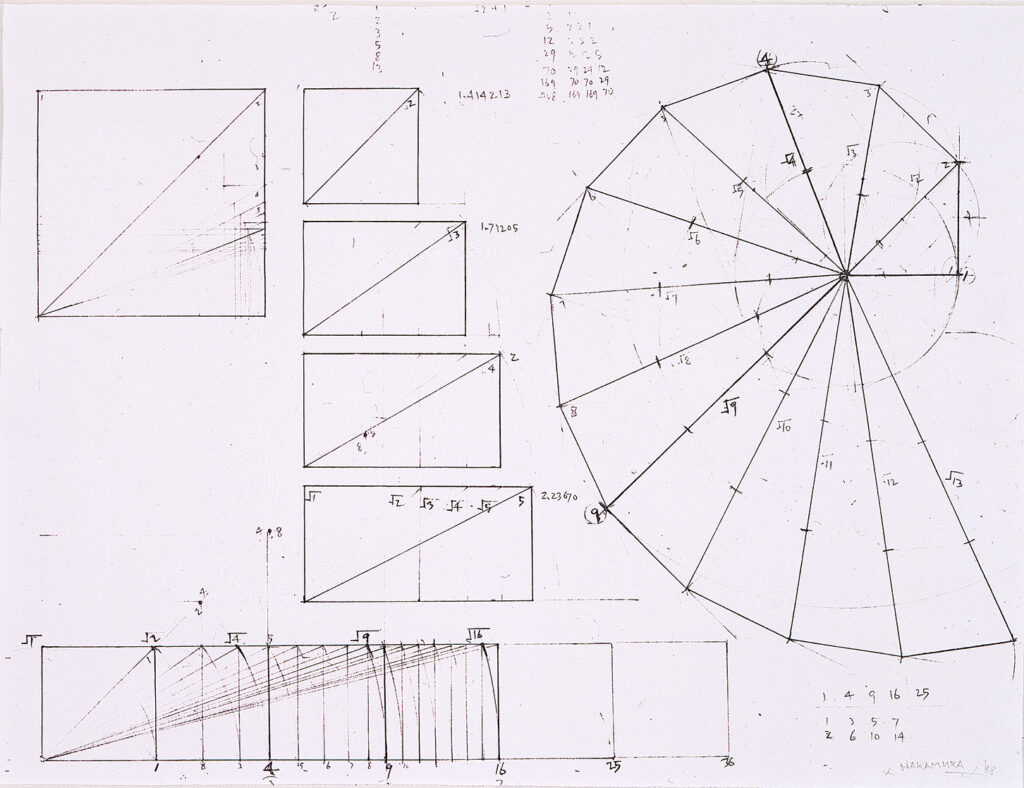

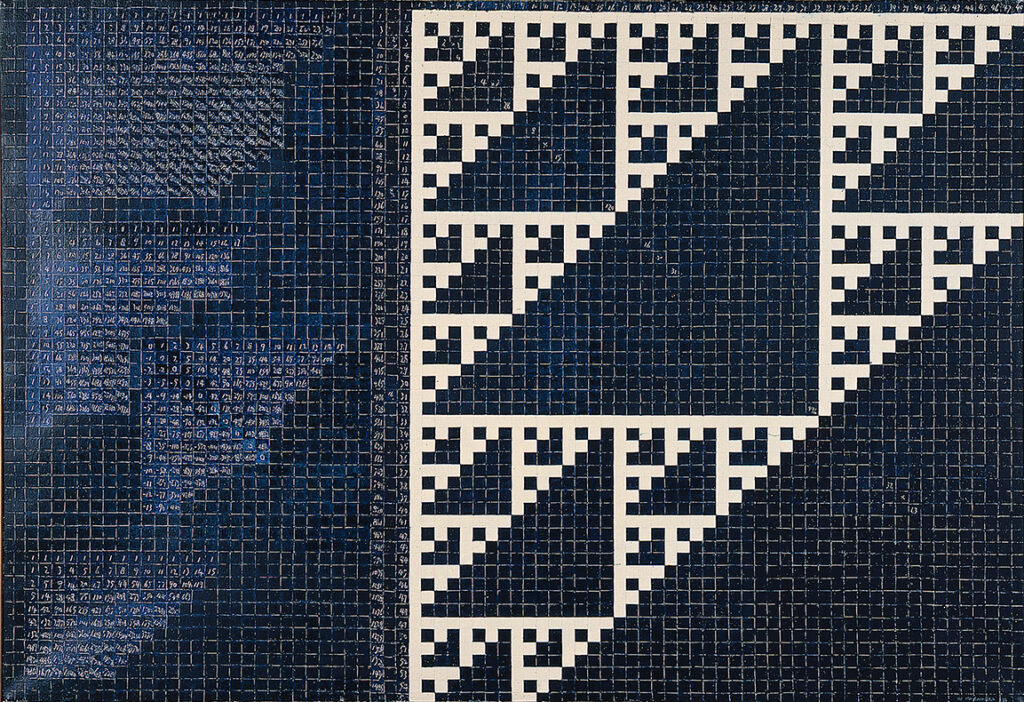

McDermott’s approach to his art carries this sense of the essential, a life-long journey to the “core” of our being, which he maintains is “untouchable” and “unreachable.” This drive for answers to primal meaning in art brought to mind the work of Kazuo Nakamura, particularly to an exhibition from nearly two decades ago at the Cutts Gallery. In a review of the artist’s work, writer Gary Michael Dault characterized the almost monastic fervour of Nakamura’s painterly researches as being the result of a steadfast conviction that “There’s a sort of fundamental pattern in all art and nature… in a sense, scientists and artists are doing the same thing. This world of pattern is a world we are experiencing together.” Nakamura’s 1983 oil on linen “Number Structure and Fractals” can be viewed as the graphic depiction of the life of numbers, each organism containing the seed of its own being. By 1980, mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot had produced high quality visualizations of sets of complex numbers while working at an IBM research center, fulfilling Nakamura’s 1956 vision of artists and scientists working in tandem.

Perhaps this drive to the core of our being has no better illustration than the Renaissance itself, set in motion by Filippo Brunelleschi’s engineering miracle, the Florence Cathedral, his invention of perspective being a product. Inspired by Roman architect and engineer, Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” drawing blended mathematics and art, demonstrating the harmony of human proportion, centering the point of perspective, here, at the naval. Clearly more than a presentation of male anatomy was intended. Leonardo believed that the workings of the body was an analogy for the workings of the entire universe – a cosmografia del minor mondo. To the Renaissance polymath, this knitting together of the lines of sight was a miracle: ”Here forms, here colors, here the character of every part of the universe are concentrated to a point; and that point is a marvellous thing.” For a shining moment, engineering, architecture, mathematics, and science found its expression through art, producing some of the greatest creative minds of all time.

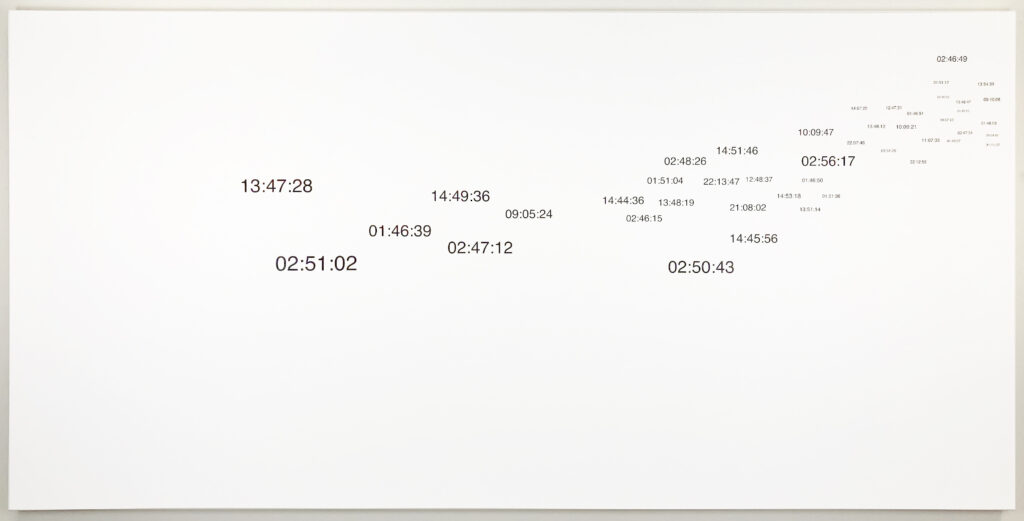

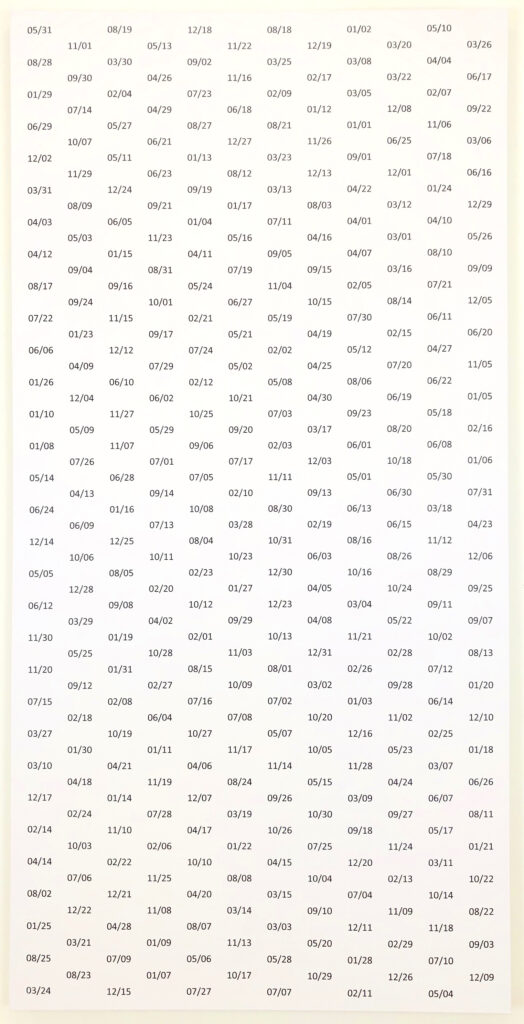

Present at McDermott’s talk was interdisciplinary artist Giuseppe Morano, to whom I owe a bit of gratitude for linking and contrasting Nakamura’s art with McDermott’s. I had become acquainted with Morano’s art at the Artist Project a few years ago, his work being singularly based in numbers and mathematics, primarily a digital printing of black numbers on white primed canvas. At the exhibition Morano’s homage to Vincent van Gogh’s “Wheatfield with Crows” the artist precisely mimicked the wing position with each crow in Van Gogh’s painting with the hands of a clock, and printing the exact time that the wing alignments signify. As I said of the work at that time, “If Wheatfield with Crows” was indeed van Gogh’s last painting, we can picture the crows taking flight at the sound of the fatal gunshot.” Morano had converted the crows into time stamps, serving here as winged metaphors for the series of events leading up to the tragedy. His “Happy Birthday: You’re so special” work is aesthetically neutral to its implied subject, until we recognize that the 366 sets of numbers printed randomly in columns signify the birthdays of every person who has ever lived. Your joy or disappointment at his gift to you may depend on whose birthday you were fated to be near, at least as how they were dispensed in Morano’s numerical universe.

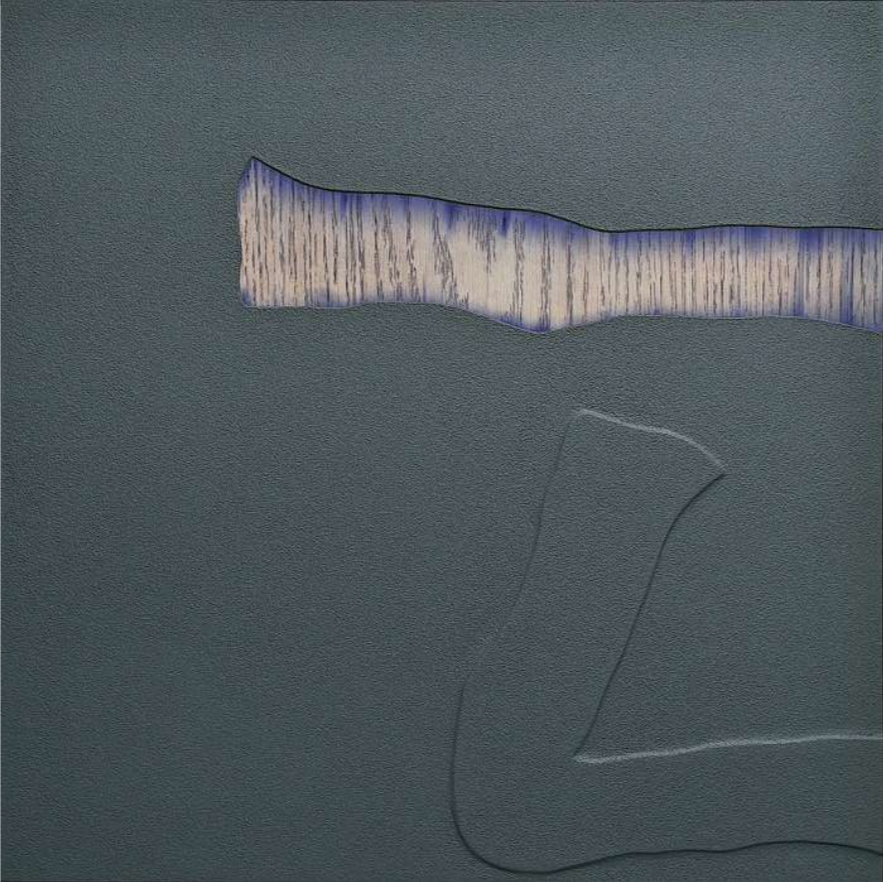

McDermott’s “You see it” exhibition is an invitation to penetrate the “unreachable” and “untouchable.” With few exceptions, the titles of the artist’s work emphatically address “You.” A solitary work begins in the first person: “I beseech you.” Yet, how much of the objective world can be inferred from any given work of art? If 605 of the more than 900 animals depicted by the Lascaux cave artists can be precisely identified today, then their art is hardly delirious phantasmagoria – rather an accurate encyclopedic cataloguing of the biosphere upon which their lives depended.

Presented here is a fragment of the see-saw of art history – the visual style of the moment being a sum of the artist’s thoughts, set against the nourishment of insight and aesthetic meat upon which the viewer is invited to feed. “You see it?”