by Mary Hrbacek

Almine Rech presents “In Its Daybreak Rising,” an exhibition of eighteen new abstract oil paintings by Sarah Cunningham. The exhibition is unusually focused and pure in its means. The semi-abstract works with representational underpinnings speak for themselves; their surprising immediacy quickly engages the viewer. One is not asked to read long texts pertaining to the show, or to contend with convoluted explanations of current trends that abound from the Metropolitan Museum to galleries in every art district in New York. Abstract painting comes in many guises; the works are often visually attractive, but ultimately fail to convey meaningful content, which would make them matter more authentically. Beauty is never wrong if it is authentic, but without an in-depth foothold, it can tilt toward the decorative, Sarah Cunningham’s works have no link to decoration. The psychologically complex works present configurations of thick worked media that create depth, movement, and inner space.

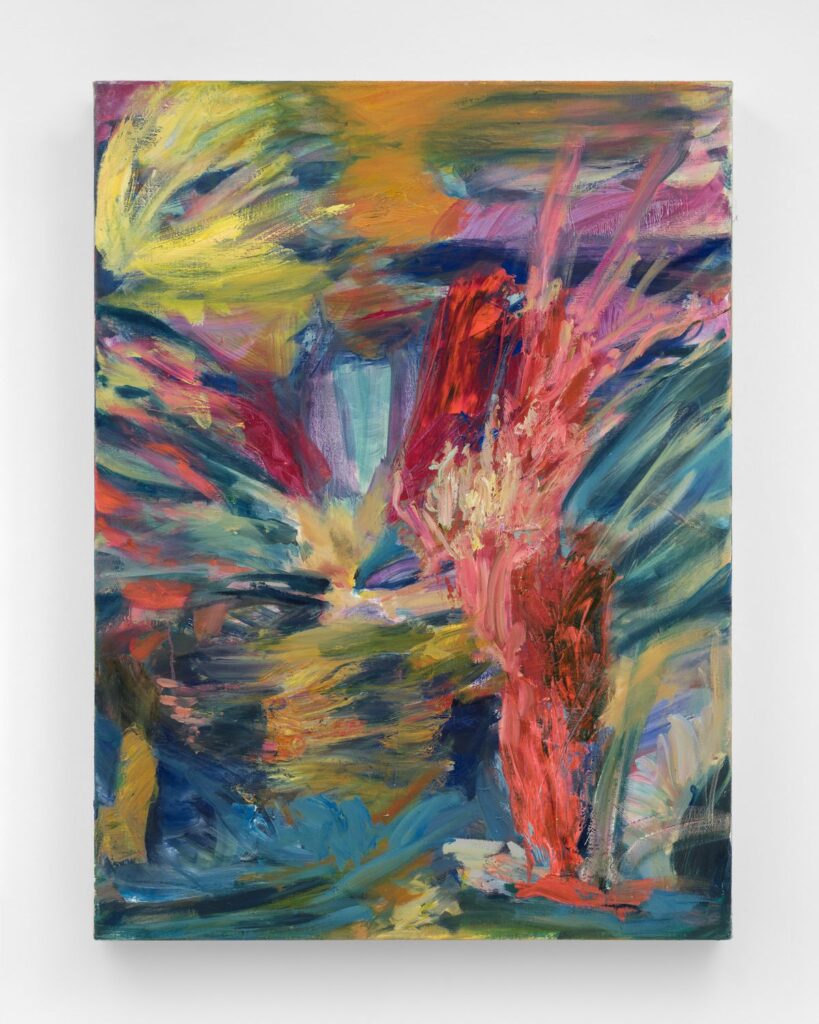

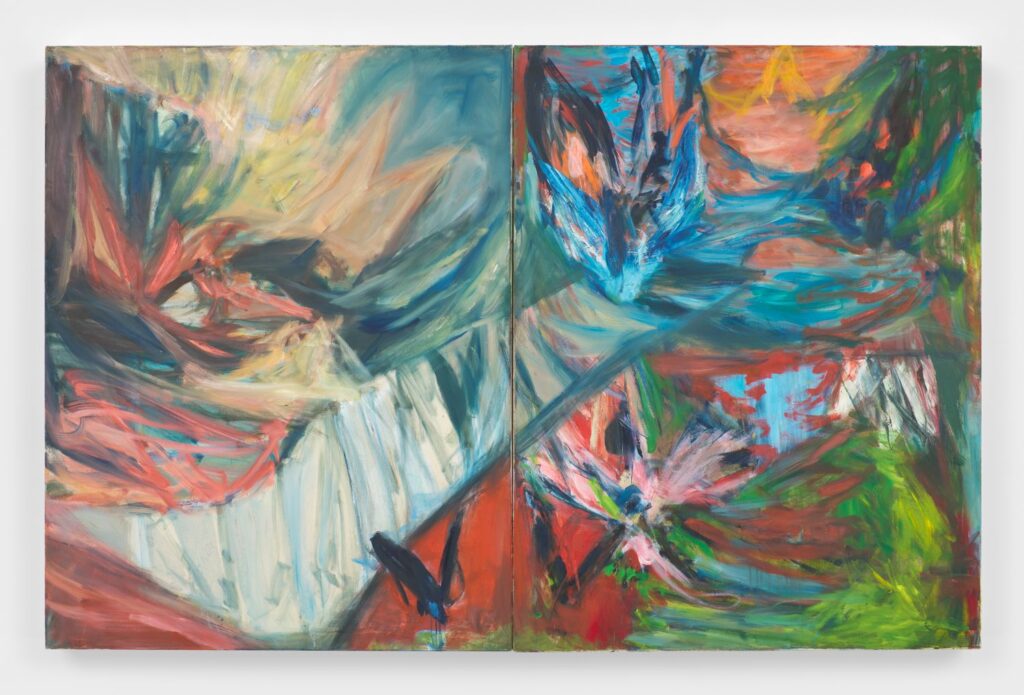

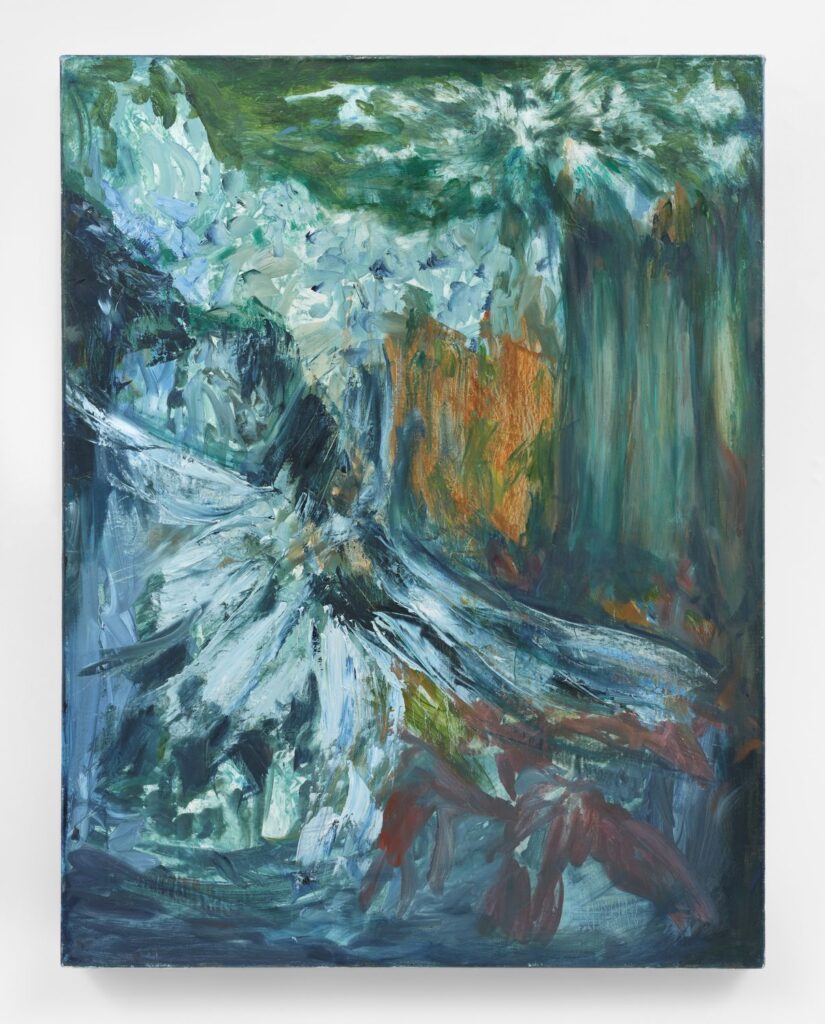

The loosely built-up, manipulated paint results in a warm relaxing vibe that sets the viewer at ease, while it draws the eye ever deeper into an exploration of the pictures’ elements. The vehicles that drive the works are the intricacies of long, medium and short strokes, thinly glazed areas penetrated with washes and scratched lines, and colors unaffectedly mingled. Beneath the independent, freely brushed strokes there is a vision of a landscape space which provides structure to some of the works in the form of organic natural elements such as flowers, waterfalls, the sky, sunlight and trees. These primeval elements make the works disarmingly genuine.

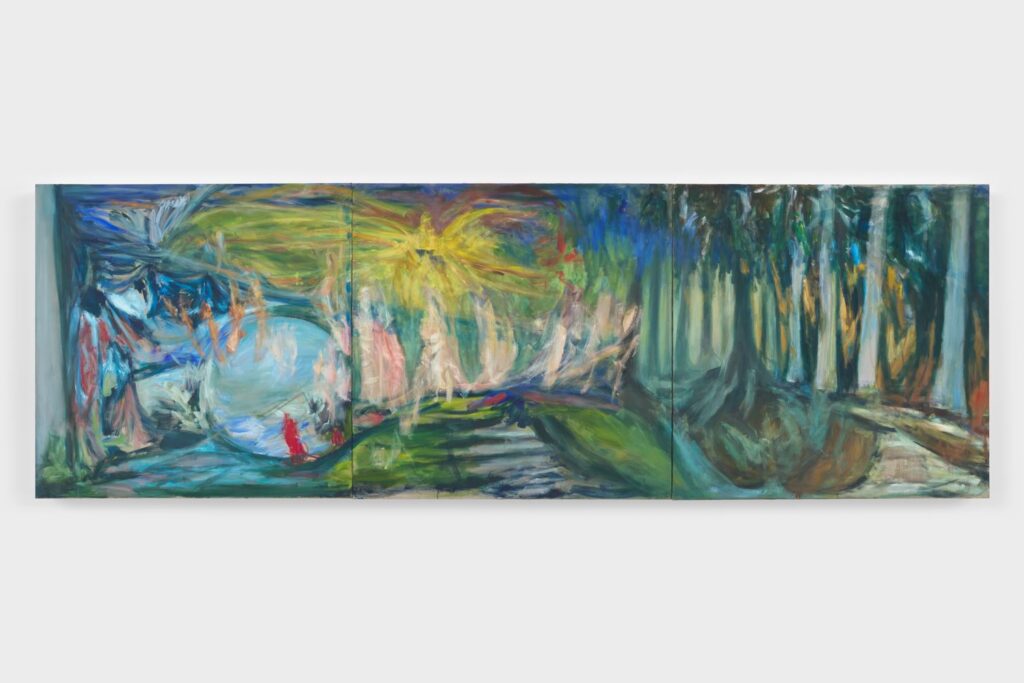

While the paintings relate to masters of the past such as the expressionists, El Greco, Albert Pinkham Ryder and even the Impressionists, they present a contemporary universal aura. Their individuality and originality are underscored by the almost diarist psychological narrative that unfolds progressively as the formats are built up and torn down in moves that stress potentiality and growth. The seemingly casual, surprisingly intuitive yet urgent application of the paint is refreshing. There is little reference to figure-ground in these works; nothing could be less descriptive. In the large triptych “A Wounded World Still Holds Us” (2022) one can realize a landscape dotted with trees, and a forest pathway that appears to have undressed dancers moving in a clearing. There is a bubble embedded on the left that illustrates a possible shipwreck, with surviving figures on the beach. Most of the works seem to evoke a twilight to dusk light effect, creating a moody, but not especially melancholy ambiance. The primary colors of slashing, overlapping strokes merge, evoking primordial seasonal intervals and rhythms.

Cunningham’s use of purple-pink, red, orange and yellow opens up the ochre and blue-green nature inspired surfaces to provide added inferences. Sometimes flower petals dominate a canvas loosely, sometimes the swirl of undergrowth is implied. Lakes are hinted at, but very subtly. What matters is the artist’s character expressed in her expansive inspirations. “River Mouth” (2021), an unexpected work that embodies an exploration of deep pictorial space, is apparently designed with a waterfall in mind.

In the work entitled “Siren,” colorful butterflies and birds appear to be flying aloft, close to a cleared walkway. Viewers must suspend judgement and relax to allow the paint to tell its story; there is only inherent poetry and imagination to lead one. The piece entitled “Turbulence” (2001) appears to be inspired by an immersive forest fire approaching two trees, which may be referencing recent global forest conflagrations. Some of the warm colored hues tinge the works with the feel of autumn or sunset, that mediates the role played by blue and green, with their intimations of nature, earth, life and renewal. Red is associated with the life force, with flames, blood, sacrifice and love, and in Japan and Korea with the sun. Yellow symbolizes life, fire and heat. The appeal of this group of paintings is their repetition of related and recreated styles and formats that put the mind at rest while engaging sensory feelings and visual insights.

The titles are mysterious and thought provoking; they comprise personal poetry that doesn’t reveal much that relates to the artist’s intentions. Some of the titles refer to machine culture, which is puzzling and enigmatic in the context of these apparently environmental images that unite the artist with nature’s patterns. Cunningham seems to be playing with the viewer, keeping any obvious interpretations undercover. “Machine Dreams,” “Dressing in Limbo,” “After-life,” “Folding Is A Kind of Fading Out,” “A Wounded World Still Holds Up,” “In Their Bilious Calling,” “Shrine,” and “Siren,” to name but a few, all present a cross between references to life, and to philosophy, in tension with natural allusions. There is a significant metaphoric narrative in effect, though underground, non-descriptive.

The blended strokes that merge together overlap potential boundaries, providing viewers an unfathomable consciousness of being inside someone’s head, flowing with the endeavors, thoughts and movements of the artist. Cunningham’s approach to the picture plane seems to reveal pure exuberance, although there are dark sections at work as well, mitigated by thickly applied warm bright hues that in some instances suggest the dawning light of day.

I find these works to be liberating. Cunningham doesn’t seem to care to please others; she paints for herself in her unfettered unencumbered style. Her distinctive moves make the works flow from one to the next to create a unified story of her mind, that expresses itself in freedom of thought manipulated by painterly interpretation. The paintings are highly sensual and visually engaging without the intercession of weighty conceptual dogmas to interrupt their authenticity. The art is alive; it is enough and it speaks for itself.