by John Mendelsohn

“What are we looking at and what are we seeing?” That is a question, spoken or not, that pervades the experience of contemporary art. This is particularly true of the sort of art that specializes in eluding obvious imagery and easy explication.

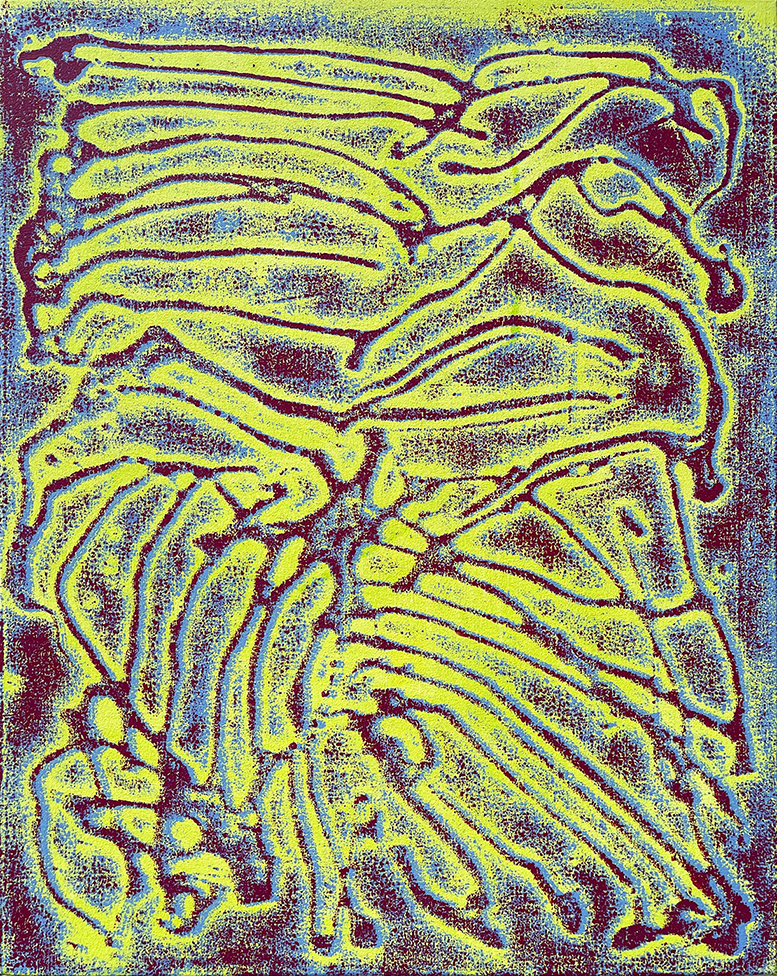

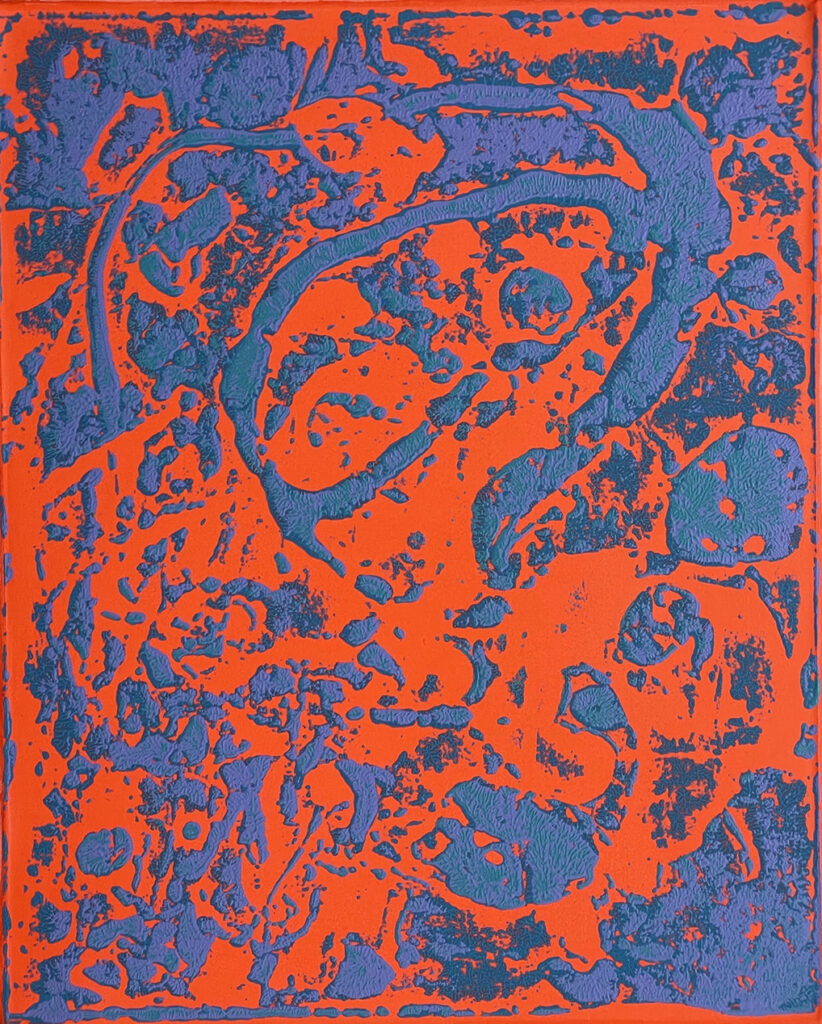

In Stephen Maine’s exhibition of new paintings, we are confronted by the residue of process, a material memory of what was once there. Maine layers a series of off-printings from plates made with modeling paste, extruded foam, and glue. This template is charged with paint that is then transferred to the canvas, in a process similar to a monoprint. But in this case, in a single painting the template carries color in successive printings, resulting in an image that appears as if in dimensional relief.

With their saturated colors, the paintings have a kind of psychedelic, ruined glamour, making a painterly virtue out of the necessity of loss of image’s original source. The paintings play with our continual impulse to seek the meaningful signal in the ambient noise, like making out an image from a stain on a wall, as Leonardo noted in his description of pareidolia.

The question of what we are looking at and seeing in these paintings remains the challenge within these works. They rely on our own need for paintings’ intelligibility – to make sense, even as we are immersed in sensuous intensity. These paintings seem to both stimulate and frustrate this desire, through chaos at a remove, a loss of the referent, an appeal to the grotesque.

When we talk about Maine’s work, we cannot help but see it in relation to Richter’s early scintillating procedural abstractions, and to Warhol’s degraded silkscreen tabloid images. Into the mix we can add the work of Simon Hantaï, and his method of pliage, painting folded canvas, that when unfurled yields unanticipated results. And even further back are artists who used the stratagems of automatism, the surrealist technique used to bypass conscious control in hopes accessing a portal to the unconscious. This approach informed Pollock’s inscribing the evidence of his physical movements at a liquid distance from the canvas.

All of these artists’ work partakes in a kind of drama wherein the authentic and the automatic continually contend. Maine partakes in this as well, while maintaining a kind of optimistic faith in abstraction’s ability to remain the language of sophisticated discourse, even as it evokes a world in flux, consumed by rupture.

The question of the artifice of art is ever-present in Maine’s work, since we experience a kind of simulacrum of the real, the gesture that is memorialized. The illusion of authenticity persists, as the work appeals to our craving for the spontaneous and the genuine.

This desire is put to the test by the artist’s work in the exhibition, with three larger and five smaller works. Two of the paintings are from a single template, in changing color palettes. As a whole, the Maine’s paintings here are in contrast to his work from a number of years ago, with their wall-sized scale and floating, anarchic spirit.

Some of that wildness remains, but a new feeling of organic growth emerges in the branching, linear patterns that structure some of the works. At times, these rib-like elements vibrate in pixilated, buzzing topographies, or alternately devolve into runic entanglements. Also appearing is a new simplicity in a number of the works, with the printed elements announcing themselves with graphic clarity and high-contrast colors on evenly painted grounds.

Stephen Maine: Typologies is at Hionas Gallery, 94 Walker Street, New York from April 21 – May 7, 2022