by D. Dominick Lombardi

If a man walks in the woods for love of them half of each day, he is in danger of being regarded as a loafer. But if he spends his days as a speculator, shearing off those woods and making the earth bald before her time, he is deemed an industrious and enterprising citizen. – Henry David Thoreau

Controlling nature, or one’s personal environment, has been an age’s old endeavor. I am reminded of the ancient city of Petra in Southwest Jordan, which was carved directly into the reddish sandstone, as one example of something of a massive and monumental compromise in that struggle between ‘progress’ and the destruction of the environment.

I have also seen first hand where Native Americans once inhabited the pre-existing cliff caves in Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, where working with natural rock formations afforded its inhabitant’s relative safety and security once they mastered the finger and toe holes they carved for climbing to the areas they farmed and food sourced. The aforementioned are exceptions to the rule, as mankind often levels and eliminates the natural environment, erasing any trace of its intrinsic beauty to form ‘functional’ towns and cities over flattened land.

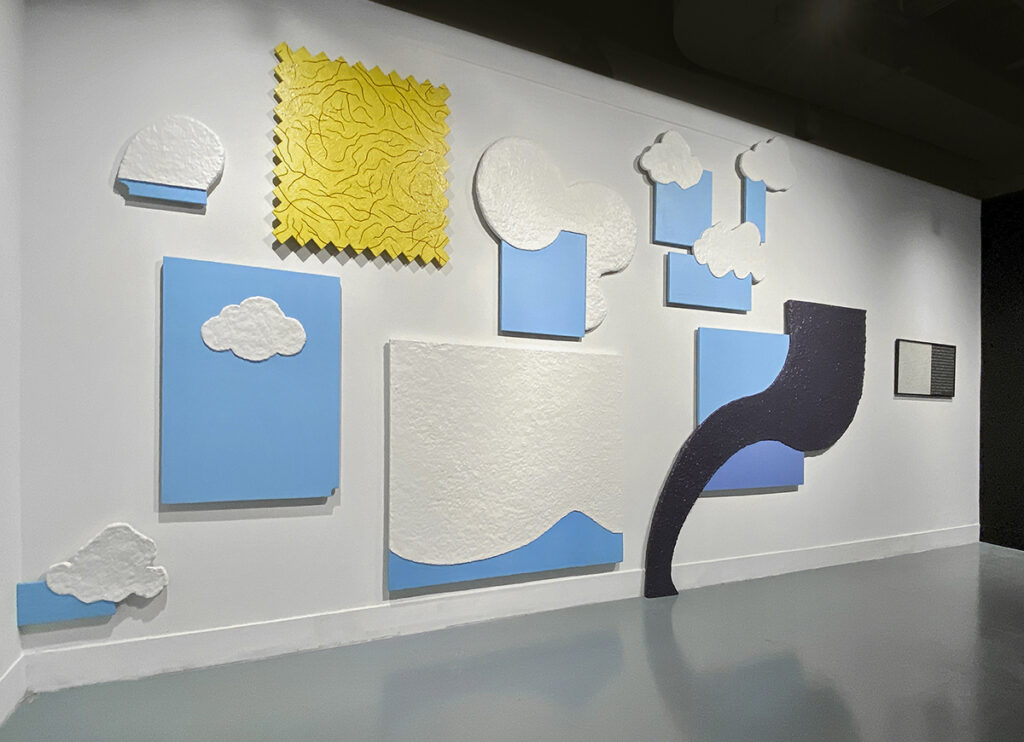

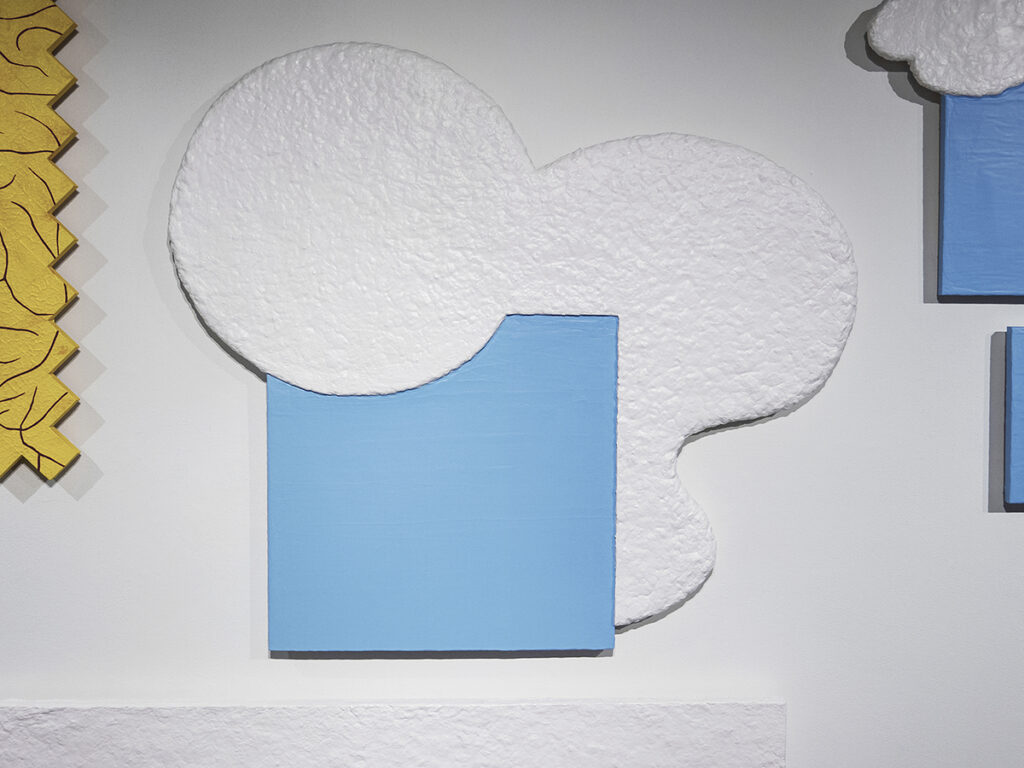

During a studio visit with Matthew Garrison this past summer, he periodically referenced the Gardens of Versailles as one of the factors that informed his work. With Garrison’s Cloud Series, we see an extrapolation of those very concepts of Versailles’ unnaturally shaped garden formations transmitted into his distilled and distinctive skyscapes. In this instance, we see geometrically shaped sections of sky that hold cotton-puff clouds that are a lot closer to cartoon renditions than reality. That injection of humor is compounded by the fact that Garrison uses many gallons of white house paint and endless boxes of cotton balls to create the clouds. After several weeks of drying time managed by wood panels and c-clamps to uniformly flatten the clouds, the paintings in this series can weigh upwards of 150 pounds – quite contrary to what one would imagine a cloud to actually ‘feel’ like up close – hence the irony.

When seen as an installation, the Cloud Series tells a story about us, how we have been trying to change the weather for decades by experimenting with cloud seeding to increase snow and rain fall where needed, to geoengineering to prevent catastrophic climate change, changes that we are forcing with the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, poor farming techniques and the production of meat. With his Cloud paintings, Garrison takes a crack at the craziness by mimicking Versailles’ approach to the shaping of their vegetation in his cloud forms, while a tangible fact, that we are actually attempting to change or manipulate the sky, comes to the surface. To make matters more menacing, Garrison adds an ominous plume of smoke in Smokestack, which traverses a sky that remains bright and ‘normal’ on top, and darkened and life dimming on the bottom. A very telling note when one considers how often the skies along the East Coast of the United States can be muddied and tinted by the wildfires of the West.

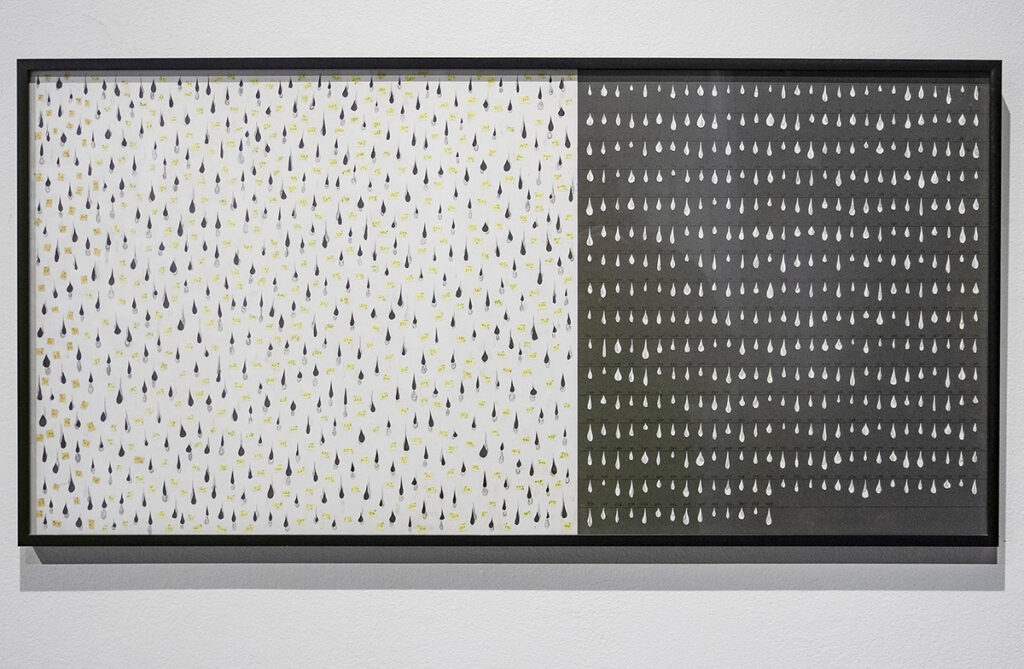

One striking juxtaposition in Garrison’s staged sky is the sun, Hand Study 5, which is comprised of a jagged, butcher-block design, heavily painted with puckered yellow latex paint and adorned with slices of paper, spray painted red that trace the creases in the palms of the artist’s, and other subject’s hands – an element that can be seen in various works that so powerfully state the omnipresence of the hand of mankind in nature. The sun, as we earthlings understand it, is impossible to change or affect, even if we could get close enough to actually do anything about its structure or power. However, in this instance, the artist has taken the aforementioned elements of hand creases and clustered cubes of painted and collaged wood to reimagine the sun as an oddly shaped and sutured form. Seen together, Hand Study 5, Smokestack and the diptych 449 Drops; which features two narratives: one grouping of numbered raindrops in a chaotic pattern on a light background, and another series of droplets arranged neatly, systematically and numerically on a dark background, all puts a fine point on our inability to work with and not against the powers and presence of nature.

In Be Right Back, Garrison has created a menagerie of communication by compiling several detailed composites of social platform, home environments. In taking screenshots of temporarily vacated roomscapes, Garrison is telling us much about the private world through the things we save or display, the fabrics we choose, the clothes we don’t put away and the belief systems we supposedly live by. Yet, inside the numerous disheveled, domestic domiciles that should never have seen the light of the computer screen, Garrison forms a rhythmic pattern that not only keys off color and scale, it skips along with periodic text and transitions propelled by the unoccupied voids that we get the sense, especially as we navigate through the days of COVID, that comfort, expression, responsibility and taste are all truly individual and more often than not, quite ordinary. And we are drawn to this somewhat disorienting display of architectural details, bits of furnishings and unmade beds the same way we are captivated by negative news casts or episodic shows that follow tortured or unhappy people around. We can’t help but look, hoping we don’t find our own embarrassing captured corner of life.

The collection of videos in Night Life, which is footage activated by the movement of wildlife, were taken in nearby woods from the artist’s country studio. Most of what we see are foraging deer captured in night vision; a creepy form of black and white photography that produces a sort of ‘negative’, infra-red appearance. There is nothing untoward meant here, however the fact that this is a nocturnal activity not usually seen by you and me – one might get the feeling of uneasiness, as if something bad is about to happen, and we wonder: “Why else would we be looking at this?” That feeling, that detachment we have from the natural world has caused that uneasiness, that fear that something terrible may occur – or – we might become mesmerized by the continuity, the commonality, the community and the determination of the animals to feed that we may see and feel a new kinship with nature. In either case it is still an intrusion, a change in the environment, albeit subtle, that increases our unwanted footprint as voyeur, while at the same time, highlighting what is actually going on in the daily lives of animals that is quite beautiful and remarkably peaceful.

The Liberation of the Saint by Garrison is an homage to Raphael’s fresco titled The Liberation of Saint Peter. In Raphael’s masterpiece, we see Saint Peter behind bars being freed by an angel aglow in a brilliant aura of white and radiating golden beams. In Garrison’s version, we see the angel replaced with a circular mirror that reflects all onlookers and passers by. The background is that familiar blue sky we see in the Cloud paintings, which is precisely bordered by freshly applied Astroturf. The sterileness and starkness of the composition is enclosed with vertical bars that clearly state containment, suggesting good and bad or right and wrong is often a subjective concept – a further nod to the master’s work, or a general statement about the state of such social endeavors as politics and religion.

The Astroturf makes another appearance as media in Quarantine. Here, Garrison’s observation regarding man vs. nature comes full circle as the classic fishing expedition becomes an ultra-focused fantasy where artful technique becomes a rather joyless and mundane conquest. And isn’t that the point here? If we spend too much time and energy making things ‘comfortable’ and knowable we lose the pleasure of discovery. Our lives become compressed and stunted and our minds simply shrink under the pressure of avoiding the outside world. We all felt it during COVID. It’s not natural to lose socialization. Homogenization as ‘quality control’ works fine in the processing of milk; but when it’s applied to nature and culture, it’s not so good.

When I think about the overall message in Nothing Left of Time, I am reminded of the concept in Japan of wabi-sabi, whereby natural change and imperfection is accepted and desired. Garrison’s art is both a statement and a warning about how we try to control that balance. We must embrace what is left of the natural world, and do what we can to restore what we have lost or we are doomed. We must contemplate the power and essence of Garrison’s art, and begin to think about what we can do to help save our planet with all of its natural bluster and beauty.

Nothing Left of Time: An installation of Works by Matthew Garrison will be on view at the Freedman Gallery @ Albright University in Reading, PA through March 6th.