by Siba Kumar Das

Susan Schwalb is at once an artist of this world and a transcendent artist. Her drawings and paintings are abstract, decidedly manifestations of the world’s geometry; they echo the belief of Latin American modernist Joaquin Torres-Garcia that geometry provides the artistic and spiritual scaffolding for all true art, in all ages and cultures. Deploying minimalism in lyrical mode, Schwalb’s art is also allusive and suggestive – a contemporary reinvention of the Symbolism of the late 19th century. It extends with great virtuosity the potential of metalpoint to evoke a numinous effect through delicacy, fineness, and a shimmering luminousness. Take an attentive look at a work of hers and you will be transported.

Back in 2015, Schwalb was the only woman artist and one of three living artists to be featured in Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns, the first exhibition – jointly organized by the National Gallery of Art and the British Museum – ever to present the history of metalpoint drawing, a history spanning six centuries of Western art. In an accompanying book, curator Bruce Weber calls her “the most widely known American artist working in metalpoint today,” and says, “She has enlarged the boundaries and possibilities of the medium.” In a book published in 2013, art historian Thea Burns pays tribute to Schwalb’s artistic achievement as well as her promotion of metalpoint, saying she’s “probably the most prominent metalpoint artist working today.” Margaret Mathews-Berenson, independent curator, writes in an essay accompanying a metalpoint drawing show she curated in 2010, “Schwalb has become the Pied Piper of metalpoint.”

Upon graduating from Carnegie Mellon University, Schwalb devoted herself to an art career dominated by brush and watercolor and pen and ink till 1974, when, inspired by an artist friend, she began drawing in silverpoint. Exploration of other metalpoints followed and, since 1975, she has worked mostly in metalpoint, pushing the medium in recent years to move it towards painting. In personal conversation with me, she has said she was looking for a fine line when she found silverpoint a revelation. Schwalb prefers to discuss her art technically, eschewing metaphysical and speculative thinking. Yet she feels that a spiritual force drives her work.

Metalpoint, especially silverpoint, took off in the world of European art when, in the 15th century, artists in Italy and northern Europe took a medium used for writing in ancient Rome and, in medieval times, for ruling and underwriting in illuminated manuscripts, and transformed it into an artistic instrument carrying a huge cultural charge. It enabled the creation of naturalistic effects, such as depicting surface textures, capturing the fall of light on objects, especially human skin and drapery, conjuring the illusion of three-dimensionality on a flat surface, and the suggesting of human emotions – the last-mentioned having the by-product of intensifying spiritual devotion. Renaissance artists utilized metalpoint to launch an artistic revolution, as Martin Gayford says in a review interpreting the show in the British Museum and the National Gallery of Art.

Its revolutionary impact realized, metalpoint usage fell away in Italy after Raphael’s death in 1520. Almost the same decline occurred in the Northern countries, though there the medium survived through intermittent usage till the end of the seventeenth century. Then during the 18th century, only miniature portraitists employed metalpoint. For the medium once again to become an important propellant of artistic creativity, we have to wait for the nineteenth century.

Catalyzed by an interest in early Renaissance art inspired mainly by the Nazarenes, a German artistic group, and by the Pre-Raphaelite painters in Britain, a metalpoint revival took root during the 1820s and, as the century progressed, became quite widespread, even entering popular culture. Mainly a British phenomenon, this revival adhered closely to Renaissance precedents but by the end of the century, with the Pre-Raphaelites having created ground for Aestheticism and the British variant of Symbolism, preludes to modernism, British artists discovered metalpoint’s potential for transcending naturalism and used it in innovative ways, building upon the art and teachings of Alphonse Legros, a French-born artist who became a British citizen and worked in the pre-Raphaelites’ slipstream. Thea Burns says that he used metalpoint (and graphite) with subtle virtuosity to show that art could respond to suggestions emitted by its materials and thereby create “a newly created reality juxtaposed to or coexisting co-equal with the objects of ordinary reality.”

The impress of this revitalization crossed the Atlantic as well and, soon after the century’s turn, leadership in metalpoint drawing became a North American phenomenon. Metalpoint usage pushed American draftsmanship onto a high ground of technical achievement and propelled that usage in new directions. Yet, possibly because American art did not break through into geometric abstraction till the late 1950s, American metalpoint exponents of the early modernist period – artists such as Thomas Dewing, Joseph Stella, Marsden Hartley, Ivan Albright, and John Wilde – produced superbly crafted metalpoint art that was innovative and experimental but not radically so.

It is only in the 1970s and thereafter that a greater transformation occurred, not only in the U.S., but in Europe as well. Referencing contemporary artists in both regions, Bruce Weber says that metalpoint is being used these days by a large and growing number of artists “in ways [the old masters] could never have contemplated or imagined.” Whether this amounts to a full-fledged metalpoint renaissance cannot yet be known, but something significant is going on. A Facebook group focusing on silverpoint/metalpoint drawing has attracted well over 600 members.

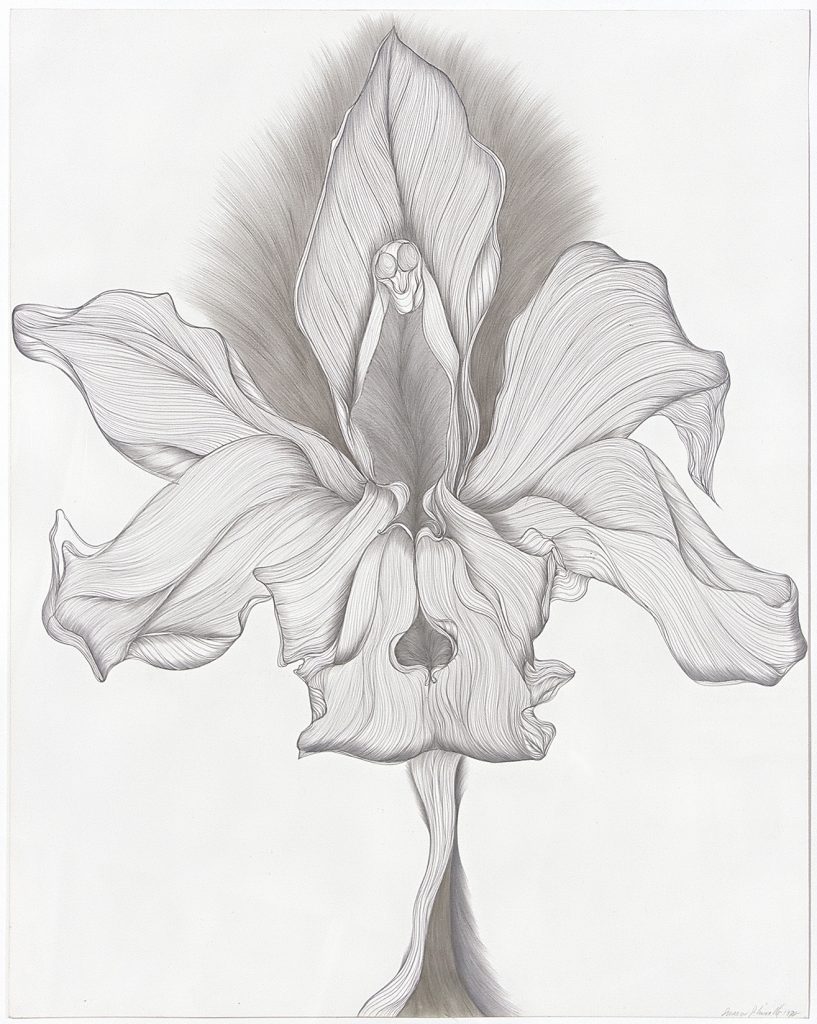

Schwalb began her metalpoint career making drawings of orchids, a motif carrying for her deep personal resonances. When you gaze at her Orchid Transformation #2, which she drew in 1978, you will be struck by the flower’s beauty and nearly muscular power and vibrancy, and as you keep looking, you will feel that it is not just alive, as if it were an actual organism – it is also a symbol for life or rather the way in which life embodies stillness amid rhythm and vitality. Close to Georgia O’Keefe’s flower paintings. Schwalb’s orchids are both naturalistic and abstract.

In the year after Schwalb made Orchid Transformation #2, she moved deeper into abstraction by removing the orchid as her direct subject and focusing more on the shapes behind or underlying the flower. A striking, strongly expressive example is Kahili I – a silverpoint and copperpoint drawing she made in 1980 incorporating the effects of melted wax and smoky marks created by singeing the paper. In this we see abstracting influences the artist took from tribal art, a spell she explored for some time. In the fifteenth century, Renaissance artists deployed silverpoint to reinforce a shift from allegory and symbolism to pictorial realism. Schwalb has moved in the opposite direction. Marc Chagall said, “You should not start with a symbol, but end up with one.”

Schwalb became more radical in the mid-1980s, when she made drawings that were geometrically abstract or nearly so, transmuting memories of landscapes she had seen. Ideas originating in the world of music contributed to the metamorphosis together with influences drawn from Rothko and other Abstract Expressionists – all gradually morphing in the 21st century into an even more minimalist aesthetic that dominates her artistic practice today.

For an early example of this aesthetic, let’s look at Madrigal #14, which Schwalb made in 2010. Bands and lines drawn in shades of dark grey with a bronze wool pad and a silverpoint stylus intersect horizontally a Plike-paper ground colored in a rich Venetian red. The bands and lines change their tones with exquisite subtlety. And the counterpointing tonality between them and the red background transports you into intense visual pleasure. Schwalb sees in her drawing an incarnation of a madrigal, a musical form that in the Renaissance served as a platform for poetic expressiveness. She makes you think of Matisse saying in A Painter’s Notes, “When I have found the relationship of all the tones the result must be a living harmony of all the tones, a harmony not unlike that of a musical composition.” In Madrigal #14 two voices interplay in a harmonious process that seems an endless becoming. This is art embodying allusion, implication, suggestiveness.

A drawing Schwalb made in 2012, Madrigal #41, applying a copperpoint stylus and a bronze wool pad to white Plike paper, signifies a deeper move into a meditative minimalism. The three empty bands in the middle of the image seem to imply an immanent presence and make you think of Whistler’s Nocturnes, particularly his Nocturne in Blue and Silver – Chelsea. These paintings “relied almost entirely for their effect upon the contrast between two principal colors and their variations”, as art historian Peter Vergo says in his book The Music of Painting. Schwalb employs white and gray to similar effect. But, building upon the modernism that bridges the century between her and her late nineteenth century predecessor, she goes further in making nearly invisible her subject matter. Her empty bands are allusively liminal in a symbolic way. Many art critic contemporaries of Whistler attacked his vaguely abstract paintings, their subjects veiled in colors inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, as lacking in substance and representing nothing. Today we find affecting the stillness and mysterious emptiness they allude to. Magnify this stillness and mystery and you will get an inkling of the numinous effect Schwalb achieves.

Let’s now go to another work of Schwalb’s, this time a painting, Polyphony XIII, which she made in 2016. Using copper, silver and goldpoint together with black gesso on Museum Mount Board attached to a wood base, she interweaves a composition of squares, a banded cross, and finely spaced gray-brown horizontal strata that are faintly mauve, especially in the middle of the image. Subtle tonal variations move some squares to the painting’s surface while others recede, creating a dynamic spatial counterpoint on an otherwise flat surface. The longer you look the more the changes in tonal variation; the more – or less – the mauve you see, and the more the interplay among the squares. And when you vary the distance between you and the painting everything changes again, especially the tones. Schwalb is echoing here Joseph Albers’s magnificent achievement in his great series of paintings embodying his Homage to the Square. Like Albers, Schwalb has made a painting that liberates light from within. Curator Heinz Liesbrock says of Albers: “…color became the medium for him that could allow the complexity, indeed unfathomability, of reality to be experienced pictorially…” Enhancing the possibilities of metalpoint through skillful artistry, she achieves something similar, offering the beholder a profound experience of reality’s slipperiness.

A few years ago Schwalb began giving her works musical titles. When Walter Pater said in 1873 that “all art aspires towards the condition of music”, he crystallized thinking pioneered by the French Symbolist poets, who found in music the suggestiveness they wanted of their poetry. Baudelaire, Verlaine, Mallarme, et al. prefigured intuitively something that neuroscience is telling us today. According to cognitive neuroscientist Aniruddh Patel, “language and music overlap in important ways in the brain” and are closely interconnected. Pater’s essay was not so much about poetry but about art (he was writing about Giorgione), and in the 20th century, under the influence of Kandinsky, Paul Klee, John Cage and many others, music and abstraction in art were seen as participants in a confluence. Schwalb inherited this heritage. By accentuating metalpoint’s strengths through a variety of technical strategies, and by yoking Symbolism to Minimalism, she has created an intensely evocative art that indeed “aspires towards the condition of music.”

Hugh Moss, art dealer, expert in Chinese art, and a painter and calligrapher, has argued that modernism’s great contribution to art was to show that art is not just the art object but a more inclusive process that embraces the act of creation, the thing created, as well as the interaction that takes place between the art object and the viewer. Whereas a focus on the art object may have sufficed prior to modernism, the impact of modernist art depends crucially on the attentiveness the viewer brings to the art object. My feeling is that Moss is saying something important though he may have attributed to the break between modernist art and pre-modernist art too complete a rupture. Surely, pre-modernist art also demanded attentiveness. Surely, there was between it and modernist art no break but a hinge. Another way of looking at Moss’s position is to recall what Philip Glass said about an insight he received from John Cage. Glass wrote in his memoir Words Without Music, “I got to know Cage in New York. Even before I met him I knew his writings on music. He brought ideas from Duchamp and Dada and surrealism – that music didn’t have an independent existence. It was a form of communication between the performers and composer and the audience. It totally reshaped the role of the listener.” In essence, the music comes into being when the listener completes the work. Putting Moss and Cage and Glass together, we could say it is the viewer who completes the work of art through attentiveness. We might also think of a great insight of Jed Perl’s that he set out thus in his essay The Art of Seeing: “Artists have to find ways to find ways to pull the audience in, for only when people come to understand that within a painting or a sculpture they can find a time that is outside of time will they want to keep looking.” Schwalb’s art snares you in this way.

She does this not just through her virtuoso artistry; she does it too through the disciplined industry she brings to her process. For her grounds, she goes back and forth between commercially prepared papers and grounds she prepares herself. In the latter case, while she has utilized other materials before, she currently uses acrylic grounds in white or black or colored Holbein gesso. She says that while she uses graphite and colored pencils to accentuate some of her drawings, “metalpoint is the only tool that permits me to draw with great precision and exactitude.” She is guided by her materials’ suggestions but also enhances their vitality through such strategies as incorporating metal leaf, using paint to color her grounds, and then exposing underlying paint.

Of the contemporary metalpoint revival, which she also highlights in her 2013 book, Thea Burns says it has “attracted artists who enjoy process and careful mark-making, and value precise refined draftsmanship and the technique’s exacting, labor-intensive yet quiet and meditative discipline.” These are the very hallmarks of Schwalb’s practice, and it is perhaps not surprising that she is seen today as metalpoint’s Pied Piper. Along with other artists, she is administering the previously noted over 600 member strong Facebook group. Metalpoint’s spreading use is indicative of something important. It is responding to a burgeoning need that surely includes, in an age when the growing ubiquity of Artificial Intelligence even includes its application to the arts, the showing of the artist’s hand as “an affirmation of human presence” (Burns).

If all art calls for a viewer to complete it, Minimalist art depends even more on the beholder’s attentiveness, as art historian Michael Fried has shown us. By bringing to Minimalism the suggestiveness and allusiveness of Symbolism, Schwalb has given to metalpoint a path to the sublime. She has been enormously innovative within a long tradition. Employing attributes and qualities of the metalpoint medium, especially silverpoint, that were apparent even in the 15th century but not developed at that time as well as reimagining new ideas that came into the tradition in the late 19th century and thereafter, she has driven a medium geared to naturalistic verisimilitude to convey expressive effects that have more to do with inner vision and an immanent perception of the world. In Symbolist mode, let me say that another way of viewing Schwalb’s achievement is to contemplate it applying these words (Stephen Batchelor’s translation) of an ancient Indian philosopher, Nagarjuna: “Without relying on convention/You cannot disclose the sublime;/Without intuiting the sublime/You cannot experience freedom.”