by John Mendelsohn

In this time of the pandemic, we resort to the virtual in order to connect. This applies to art, so I will be writing about an exhibition that I have seen only through digital images. The analogue experience of painting seems all the dearer as we experience it once removed.

This sense of what is lost and what remains pervades Melanie Vote’s exhibition, The Washhouse: Nothing Ever Happened Here. It takes us to an old farmstead and shows us imaginal glimpses of the derelict remains of another time. It is as if the artist has teleported herself to haunt an ancestral place (Vote grew up on a farm in rural Iowa) and conjure up visions of it for her and us to hold onto.

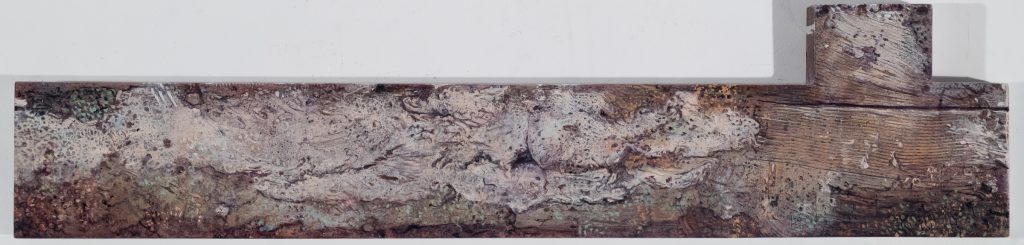

The washhouse of the show’s title is depicted in three small plein air paintings of the interior and exterior, but the main focus is on near life-size fragments of the building’s doors, boards, window, foundation and roof. Everything is painted with a kind of loving attention to the peeling paint, the weathered colors, and the clear, strong light that illuminates everything. The trompe l’oeil effect of sunlight and deep shadow has a paradoxical effect: convincing us of the illusory reality of phantom elements of the outbuilding.

The “Nothing” in the title has a double meaning and reflects the dual nature of Vote’s art. It means nothing out-of-the-ordinary, and signals her respect for the wonder of the observable world. At the same time the word leaves us with the uneasy feeling that “something” happened here that cannot be spoken of directly. It may be the hard work that took place in the washhouse, an unspoken trauma, or the disappearance of a whole way of life.

Previously in Vote’s paintings, this sense of unease and ambiguity arises in different pictorial contexts: a porcelain ballerina figurine appears like a colossus en pointe above a farm field. A figure, based on the artist, with eyes closed and holding a bouquet, is seen from above, lying on an Italianate mosaic floor. A naked, mud-covered female figure crouches, hiding in the grass with an empty pick-up truck in the distance.

In all of these paintings, and many more, the surreal and disturbing coexist with everyday reality, at times landing on the dream-like, the weird, or the tragic. In the current exhibition, this unsettling tendency appears both within and beyond the paintings of the washhouse itself. In three works, a toddler’s dress, a pair of denim overalls, and a mason jar, all levitate against a disconcertingly bright blue sky, a recurring motif in Vote’s work. All exist without a human to fill them or hold them, as if the rapture had taken place and all that is left is the evidence of what had been emptied out. This feeling of the tenuous artifact of times past extends to the two paintings of old photographic portraits transcribed in a soft, dusty magenta.

Nostalgia and sentiment are touched upon in Vote’s work. She, and we, are made vulnerable to what moves us, even if we resist its pull. The American heartland is a contested cultural and political touchstone, but this painter approaches is it in its complexity: as plain-spoken evidence and as lost innocence embodied in symbols to be held up to the light and examined.

The heartland in the personal sense is evoked in the washhouse as a ghostly sculptural installation, framed out in wood, sheltering only a small, conical mound of concrete and salt, like the tailings of an hourglass.

Vote is a very talented realist painter in the American tradition of John Frederick Peto, Andrew Wyeth, and Rackstraw Downes, devoted to the faithful rendering of the world, which perforce gives way to the unfathomable strangeness of life. The question of talent in Vote’s case begins with her ability to represent the growing world, skies, objects, and figures with a remarkable fluidity and concision. Talent in art is like a magician’s skill, necessary for the task, but in itself not sufficient. Or like the athlete with “a million-dollar body and a ten-cent head”, talent on its own can lead to nowhere. For Vote, her talent leads her to a place where the imagination can live within the image, a poetic transport.

The exhibit was on view at the Equity Gallery on 245 Broome Street in New York City between March 12 to April 18, 2020