by Emese Krunak-Hajagos

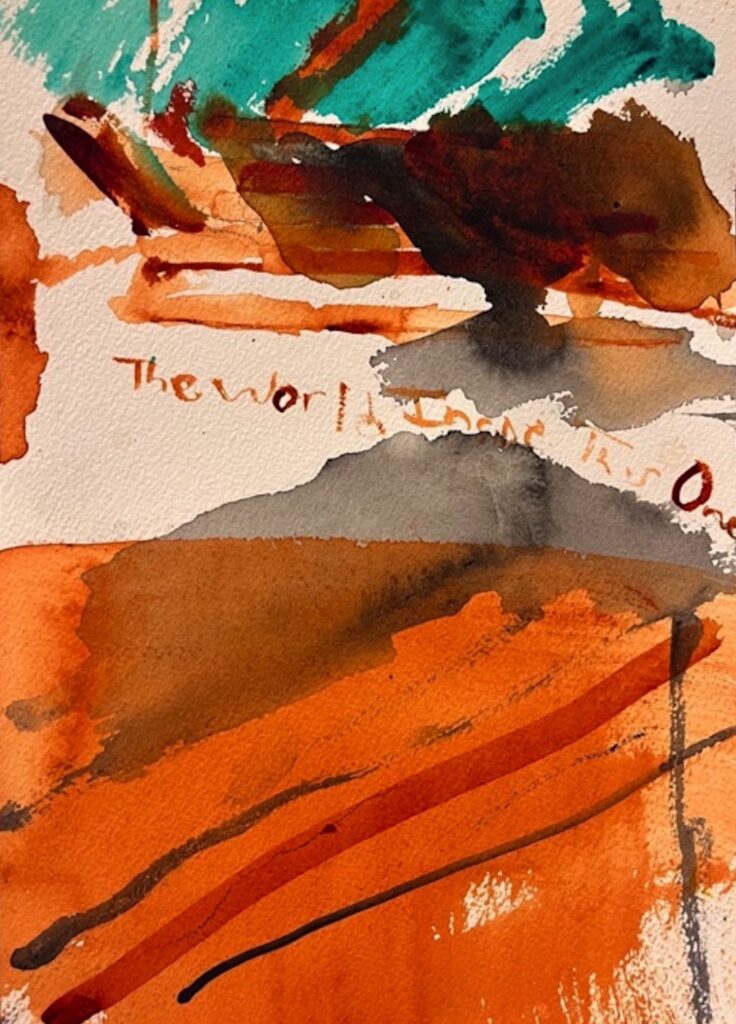

Seeing the description for Sylvia Galbraith’s Loretta’s Place in the catalogue for CONTACT 2025 I was hooked right away. Then I received an email from Abbozzo Gallery promoting Galbraith’s exhibition and the image looked as though it was in 3D—projected on the wall of the gallery. But when I finally visited the gallery, I saw the actual artwork—a large photograph on the main wall. I stood rooted in front of it, forgetting about the place and time— I just floated into its magic world.

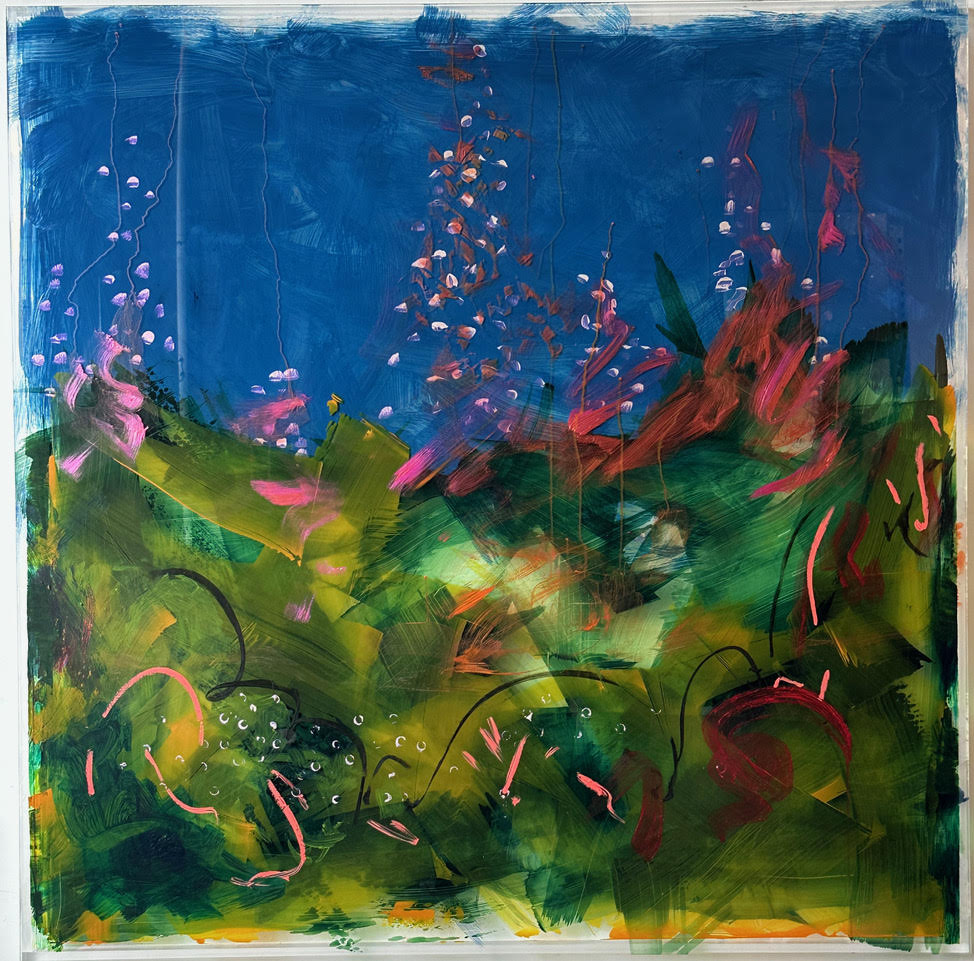

There are two different worlds combined into that one image of a rather abandoned looking room with a bed frame, as though someone had just departed or the room was waiting for a new occupant. There is a rug on the floor and wood we expect to see on the floor now on the ceiling. But what makes this image unique is the upside-down landscape on the walls. Galbraith used a camera obscura when photographing the landscapes in Newfoundland, so the inverted images are inverted. But it is much more than that. Neither the room nor the rural landscape is interesting in its own. However, through combining them in this way, they undergo a metamorphosis. The interior opens and the landscape becomes part of the room, but not like a picture on the wall. Grass grows, buildings emerge, and we no longer know when the inside ends and the outside begins. Inside and outside become one, a mesmerizing symbiosis.

The Exhibition Statement mentions that the artist was “particularly interested in relationships between buildings and people”. However, none the photographs include people. Galbraith talks about people in their absence, like poetry does. The objects and landscapes resemble history, social status and there are real landscapes in their physicality. But what is physical? Can it be modified by our perception or even by the technique of the camera obscura? When does reality end and our dreams and memories start filling the place? In these photographs you can no longer separate them, they merge, creating an illusion that overshadows any possible reality. Looking at them you find yourself in a very different world, where interior and exterior no longer exist; an ethereal place has been created.

The title of the exhibition What Time Is This Place?, is very important. The photographs depict the rural landscape of Newfoundland in reality, as an outpost with common buildings. How do those people get here? Why? Is it an escape or a conscientious choice? Do they fit in or misplaced? We can guess their history, past and present and their social status. In Loretta’s Place the bottom of the walls in the room are sky-blue, the landscape is green, the buildings are yellow and white while the floor, the bed and the ceiling are dark, creating a dramatic contrast. The bed made me think of possible interactions between objects and people. It is just the frame, hinting at the absence of a person. But what does an absence really mean? Years ago, when I moved into my apartment, there was abandoned furniture in it that an old person left behind. For some time, I felt the presence of him, like a imprint of his memory was still there. The same is true for Galbraith photographs. Loretta might be a poor person, in a small, rural place, who still needs to buy a mattress and bed clothes. Very little else can fit into that tiny place. I think she is somewhat misplaced. This room can’t be the place she dreamed about.

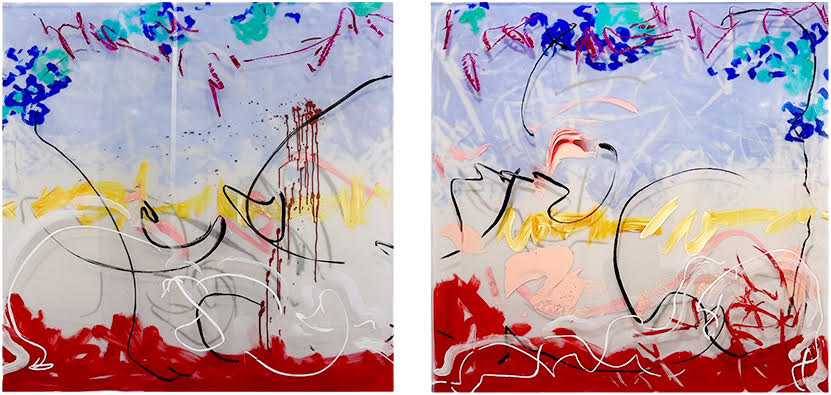

Gary’s Place, Living Room (2019) is a comfortable space with a couch and framed pictures on the wall, that are overlapped with the landscape. A piano at the wall suggests that he is a music lover. His story is very different from Loretta’s. I am aware that I am creating my own narrative here, and I am sure everyone else will do the same. It is a good thing to be so deeply involved in the image.

Some of the photographs give away their locations, like Main Road with Boats and Butterflies (2022), where the landscape is dominant. It is a nicely painted room with an antique lamp and books on a dresser, suggesting that the person who lives in it can afford beautiful, expensive things. The landscape depicts a harbor and a more populated area, a village or a small town. Butterflies fly out of the landscape, further confusing the viewer about where the landscapes ends and the interior takes over. The ceiling is another photograph that looks like a rock with some grass. It is not easy to decipher what we see or where we are.

archival pigment print on Hahnemuhle Gloss paper, 24 x 36 inches. ©Sylvia Galbraith, courtesy of Abbozzo Gallery

Morning in the Red Cliffe Kitchen (2024), located in a town, where the only thing you can see is the wall and windows of the neighboring building, giving me the feeling of a suffocating, little space. Everything is old—almost grandmotherly—the stove, the couch, covered with a blanket, a chair with a pillow, the lace curtain. As in all Galbraith’s photographs, the colors are important. The vibrant reddish brown on the left contrasts the white stove, the shining kettle and the white fence, creating a quiet interior.

Each photograph combines the inside of a living area with the surrounding landscape, focusing on the interaction between them. Every place has a strong impact on the people occupying them. Our personality is formed by our surroundings, whether it’s a busy city with noisy traffic or the countryside with a lake or ocean. According to that we become busy, hurried or eccentric, peaceful.

Our influence on the landscape can be positive or hurtful. I also believe that we may influence the buildings we live in. Whatever we do—work, cook or play the piano—our happiness or sadness leave a print on the walls and our memories live on in them. These photographs capture these ideas beautifully. As gallery manager, Blake Zigrossi said, they are more than photographs, they are “meta-photographs”, metaphors of our life.

Sylvia Galbraith, What Time Is This Place?, May 9 – June 7, 2025, Abbozzo Gallery, 401 Richmond Street West, Suite 128, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Fri 11am – 6pm, Sat 11am – 5pm.