by Siba Kumar Das

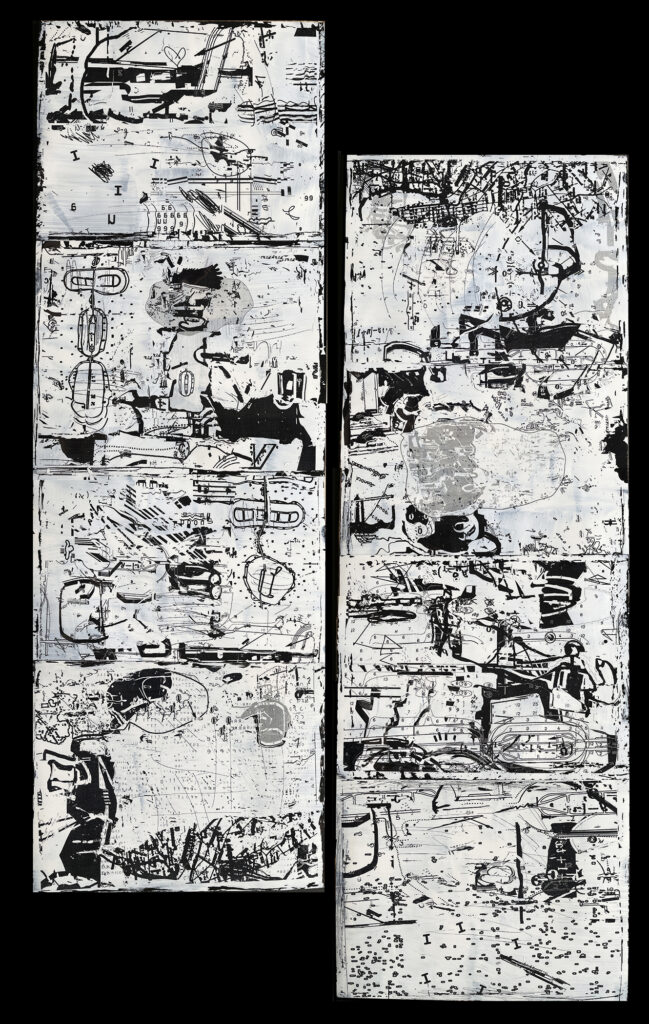

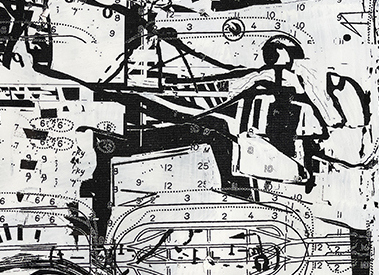

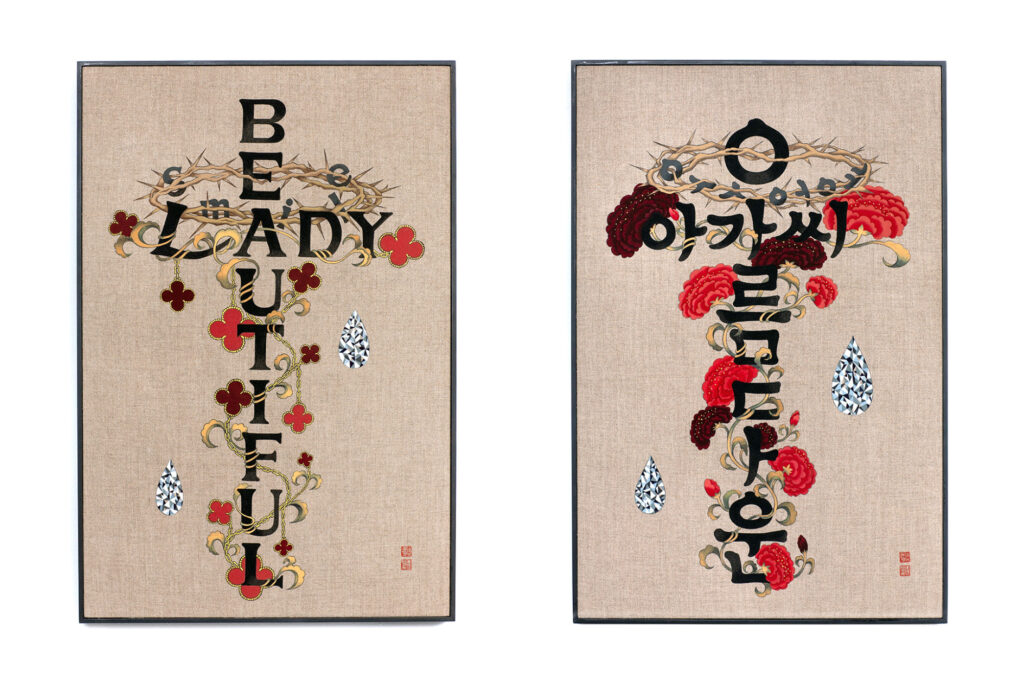

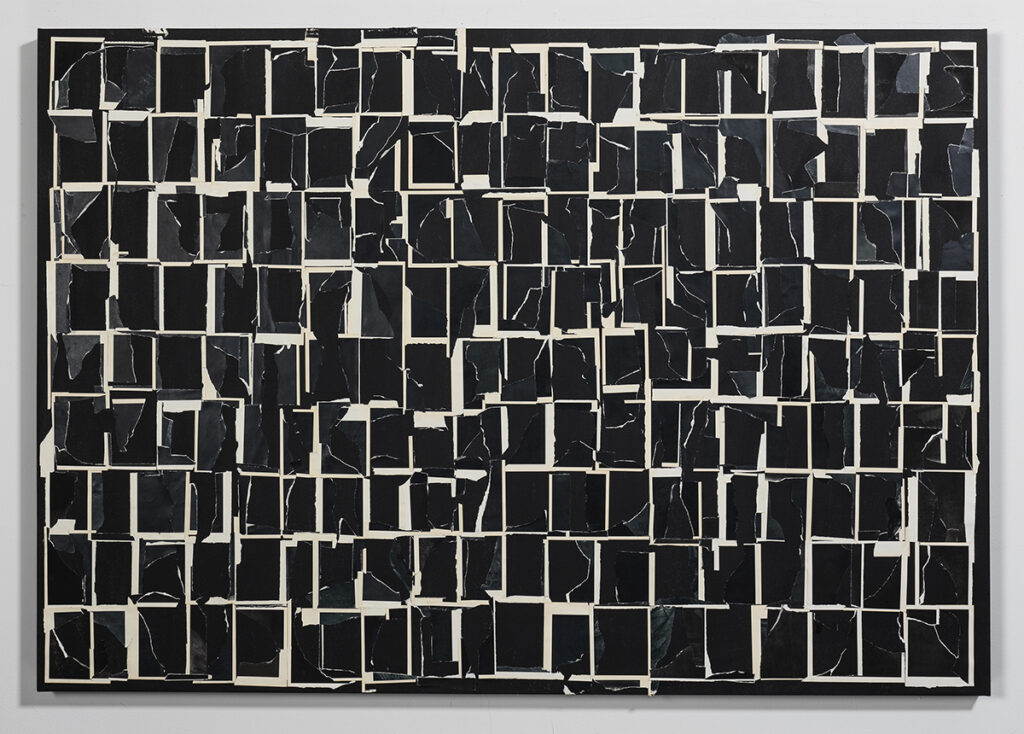

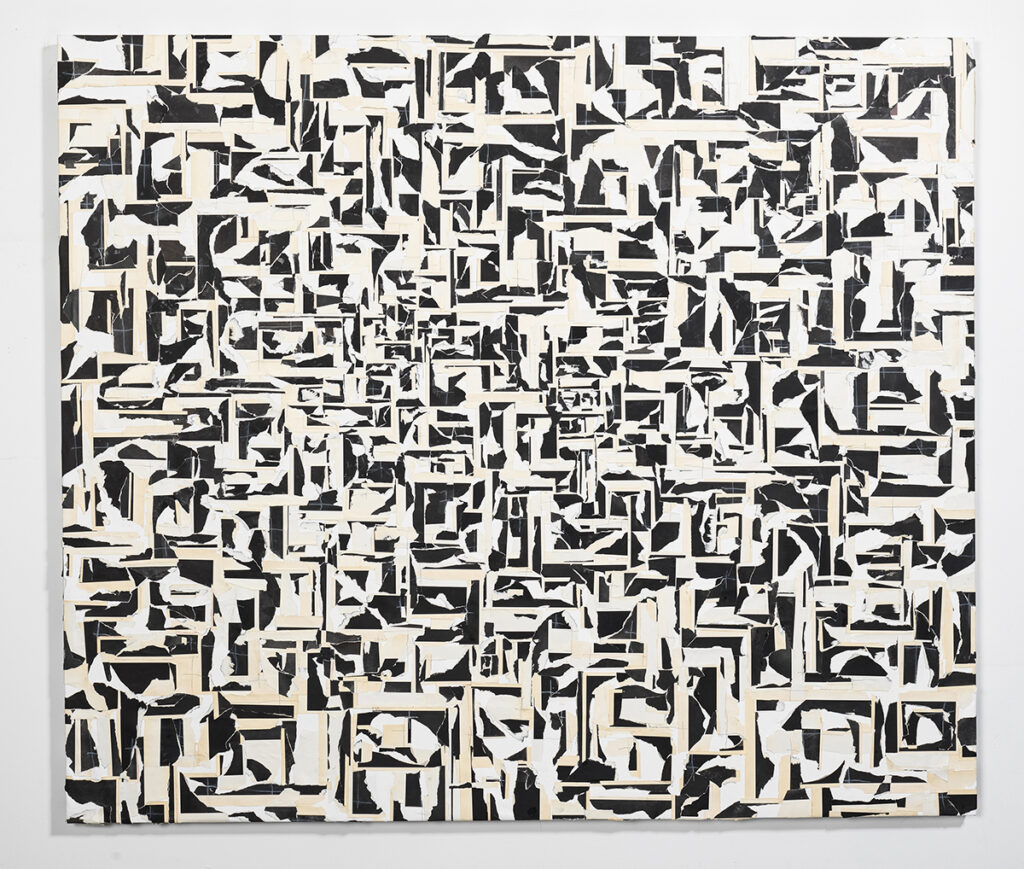

Nigerian-American artist Victor Ekpuk sees himself as an indigene of the West African culture which engendered Nsibidi, an ancient ideographic communication system that is both textual and performative. Native to the Ejagham peoples of the Cross River region shared by Nigeria and Cameroon, Nsibidi likely originated around 400 C.E., spreading to the neighboring Ibibo, Efik, and Igbo peoples. During the Age of Slavery, it also crossed the Atlantic, taking root in Cuba and Haiti. Ekpuk draws inspiration from Nsibidi to create dense sign-and-symbol networks that dominate his art, giving it evocative, expressive power. These networks also include signs and symbols arising from his own memory and imagination, as well as ideas from other cultures. Utilizing all these resources, Ekpuk has developed a unique, personal vocabulary that embeds in his art a symbiotic, rhythmic interplay between art and writing. He has gone far beyond the Nigerian artists who preceded him in utilizing Nsibidi as part of a merging of Western modernism with Nigerian and African ways of art-making.

Love of drawing has also pervaded Ekpuk’s journey as an artist. “I am almost always painting on my drawings or drawing on my paintings,” he says, revealing that, at core, it is drawing that drives the force of his art. This fuse manifests itself even in his sculpture, which he sees as his passion for line finding three-dimensional incarnation. When Ekpuk creates his enormous site-specific ephemeral murals for which he is well-known, his command of line is such his creation virtually flows out of him as a stream of consciousness.

His drawing fluency made Ekpuk a successful illustrator and cartoonist at The Daily Times, a Nigerian newspaper where he worked from 1990-1998 upon graduating from the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University). Owing to the authoritarian military rule that Nigeria continued to endure during these years, the illustrations and caricatures he drew for the newspaper to enliven its articles and news reports were so constructed they spoke to their readers “between the lines.” In an illuminating article on Ekpuk, art historian Amanda B. Carlson suggests that his work as a journalist-draughtsman imparted experiential depth to his artistic exploration of Nsibidi’s graphic attributes. Referencing Julia Kristeva, she also draws attention to the intertextuality informing his works – an attribute that surely drew formative sustenance from the subtle dialogic relationship between text and image that he created for the newspaper’s readers.

With the Princeton University Art Museum’s main premises currently closed for a complete rebuild, Victor Ekpuk: Language and Lineage is on view at Art@Bainbridge, a gallery project of the Museum located in downtown Princeton. Four available rooms show seventeen selections from a thirty-year career. Embedded on the museum’s website is a downloadable brochure, which is also available in hard copy at the show. This document contains a biographical statement on Ekpuk, brief introductions by the curator, Annabelle Priestley, to the artworks in each room, and comments by the artist on specific works and his practice in general. Using the hyperlink given above, readers of this review-essay might like to download the brochure or pick up a copy at the show.

An impression that you might take from the exhibition as a whole is that Ekpuk’s muti-media artworks are at once abstract and figurative. A twenty-first century artist, he has internalized the lessons of the previous century’s art. You might also note that, within his hybrid style, the impulse of his practice is to grow the abstraction without detaching himself entirely from its figurative attributes. Take a look at Prisoner of Conscience, 2002 in gallery 4 in conjunction with the brochure’s Figure 1, House with Crouched Figure Inside, which the artist made circa 1994. In the more recent image, Ekpuk has so stylized his depiction of the prisoner’s plight you feel their physical confinement and psychological pain in a direct, visceral way, and the more you look at the picture, the more its semantic value unfolds in you, including the message of the light streaming in though the tiny window. He has also substituted the hatching of the earlier picture’s substrate with his Nsibidi-based script forming a new substrate. Here he depicts symbolically the violence attending the prisoner’s capture even as it shows a solar eclipse promising hope through time’s passage. On a broader and deeper plane, it also alludes to a universe of endless signification clouded by ambiguity. The artist has said that it is not necessary for the viewer of his script-based art to read it in granular fashion but rather to sense its meaning through feeling – that is, in an oceanic, abstract way.

Most artworks on display depict the human head, in full or part. Referencing his art as a whole, Ekpuk says, “All portraits in general, whether I call them portraits, masks, or heads, bear the idea of the human head as the center of human consciousness. Through the years, I have devised ways to portray the head, to stylize the form and make it abstract, looking for the essence of the form of the head.” This is not the pursuit of abstraction for its own sake. The aim rather is universal signification.

The head in In Deep Water (gallery 2) contains a dense agglomeration of signs, symbols, and scribblings, so dense that the density may itself be a key message of the drawing. Ekpuk explains in the exhibition brochure that his drawing “pictures the head of a Black person” in America so weighed down by life’s circumstances they are “still struggling for air.” At the top of the head, however, is a sun-like spiral that may signify hope. And this, indeed, is intertextuality in action in the context of abstraction, sun-like spirals being a recognizable Nsibidi symbol.

For a striking example of the power that Ekpuk conjures through both abstraction and intertextuality, linger, please, when in gallery 3 you reach the acrylic painting Royals and Goddesses. The scarlet of the striations modelling a king’s head as well as coloring the dots that form his crown is set off by the underlying dark green background, which in turn is made more intense by the grey-green Nsibidi-like symbols providing affective depth to the painting. The overall effect is one of spectacular beauty. Then when you consider that, through his imagery, Ekpuk is recalling for you the Ife bronze heads of Nigeria, the fruit of a sophisticated cultural and artistic tradition that flowered more than half a millennium ago, you might say, “This is truly awesome.”

Ekpuk often listens to music when he makes art. It’s even important to him intertextually, as the soundtrack in gallery 4 shows. Featured there is the music of Nigerian musician Fela Kuti (1938-1997), whose culturally hybrid output, especially his lyrics, augments the semiotic power of Ekpuk’s drawings, such as the work Still I Rise displayed in the gallery, as the exhibition brochure affirms.

So proud is Ekpuk of his West African cultural and musical heritage he says that in his art-making, he is realizing an inheritance that is partly genetic. We have previously noted the stream-of-consciousness mode of much of his artistic practice. So primal and fluent is his drawing, he often gives you the feeling that his art originates in a bodily drive, akin to something emerging from his unconscious. In essence, his art exemplifies Julia Kristeva’s thinking not only with reference to intertextuality, as discussed above, but also in respect of the semiotic mode of the signifying process, the mode she thought found expression in music, dance, poetry, and visual art, the very things that animate Ekpuk’s creativity. Kristeva spoke of bodily energy and affects driving language use. In similar vein, art and writing dance together in his oeuvre impelled by the personal Nsibidi-based vocabulary that he has developed.

For Kristeva, the signifying process continues to have a second mode, namely, the symbolic, which uses language as a stable sign system that includes grammar and syntax. The semiotic and symbolic are also intertwined, with each vitalizing the other. What we see at Art@Bainbridge testifies that in Ekpuk we have an artist whose work illuminates the continuum that unites the two modes. Back in 2017, when the Morgan Library and Museum organized the exhibition Drawn to Greatness: Master Drawings from the Thaw Collection, Jay A. Clarke of the Art Institute of Chicago suggested in a catalogue essay that “there is still a great deal to uncover in terms of the relationship between drawing and writing.” She then said that “the formal semiotics of drawing are ripe to be explored in new ways.” The wonderfully-curated Princeton University Art Museum show on Victor Ekpuk says to us: For a distinctive, cross-cultural contribution to such exploration, look to Ekpuk’s artistic achievement.

The exhibition Victor Ekpuk: Language and Lineage is on view through October 8, 2023 at Art@Bainbridge, a gallery project of Princeton University Art Museum. The gallery is located at 158 Nassau Street, Princeton, NJ. For more information, visit https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/